Bengkulu, October 1685: The fort stood atop a small hillock on the banks of a coffee-coloured creek. To the west the Indian Ocean stretched blank and white and empty. To the east the dark wall of the Bukit Barisan mountain range rose like a stalled tsunami, a grey curl of monsoon cloud spilling from its lip.

A European ship was moored offshore – the first of its kind to pass this way for many months. Inside the fort – little more than a few mouldering huts ringed by a wonky wooden palisade – two men were busy writing. Benjamin Bloome and Joshua Charlton, the English overseers of this sad little station, had been at their post since June 24, but the passing ship was only now providing them the chance to send a first message to their British East India Company overlords at Fort St. George at Madras in India. They filled 18 densely packed pages with restrained accounts of their frustrated attempts to establish an effective pepper trade before finally coming to the crux of the matter:

We shall now give Your Honour an account of our woeful state and condition, which god grant better. We are by sickness all become incapable of helping one another and of the great number of people that came over not above thirty men [are] well … of the black workmen [there are] not above 15 that is capable of working; of them are dead about 40 and daily [more] die, for he that falls is hard for him to rise. All our servants are sick and dead, and at this minute [there is] not a cook to get victuals ready for those that sit at the Company’s table, and such have been our straits that we many times have fasted. The sick lies neglected, some cry for remedies but none [are] to be had: those that could eat have none to cook them victuals, so that we now have not living to bury the dead, and if one is sick the other will not watch, for he says that better one than two dies, so that people die and no notice [is] taken thereof…

For Bloome and Charlton, chiefs of what had been planned as a lucrative imperial outpost, Bengkulu was already proving to be hell on Earth.

The British station at Bengkulu – or Bencoolen as it was known at the time – was one of saddest of all imperial follies. For much of the 17th century, British and Dutch traders had vied for control of the lucrative spice trade out of Indonesia. It was the Dutch who eventually got the upper hand, evicting their rivals from Java and Maluku. The ousted British then went looking for an alternative base in the region. They had the misfortune to choose Bengkulu, on the bony western seaboard of Sumatra.

The place had long come under the loose suzerainty of the Minangkabau sultanate of Inderapura, but it was a place of singular insignificance, even for the locals. It had no natural harbour, was far from any major population centre, and lay on completely the wrong side of Sumatra – miles away from the busy Straits of Melaka along which almost all shipping had passed since the dawn of human history. It also had the most horrifically morbid of climates, swarming with malaria- and dengue-carrying mosquitos, and periodically swept by floodtides of cholera and smallpox. But for some reason the British believed it would become a successful pepper-growing plantation and a burgeoning way-station of international trade. It never made a penny of profit, and for well over a century it sucked up endless lonely lives.

The first challenge for the British was in getting anyone to go to Bengkulu – which was officially established on the basis of some slightly shaky treaty arrangements with both Inderapura and the local Rejang chiefs. From the outset they had to rely on slavery for manual labour. A number of African slaves had come out with Charlton and Bloome, but they were as susceptible to the noxious climate as the Europeans, so the Company took instead to buying large numbers of Southeast Asian slaves, particularly those kidnapped from Nias by local pirates.

When it came to European staff, meanwhile, anyone with the misfortune to pass by was in grave danger of being pressganged. That’s what happened, in 1690, to William Dampier, a gloriously disreputable globetrotting vagabond, who in the course of his seafaring career managed three complete circumnavigations of the Earth. During what was meant to be a brief stopover in Bengkulu, he found himself bullied into becoming chief gunner at the fort. He was promised that it would only be for a short stint, but he quickly discovered that the new governor, James Sowdon, had absolutely no intention of ever releasing him from his post. Dampier was by no means impressed by his boss: “I soon grew weary of him, not thinking myself very safe indeed under a man whose humours were so brutish and barbarous.” When, in early 1691, one of the infrequent passing ships dropped anchor offshore, Dampier wriggled out of a window in the fort wall by moonlight and made his getaway.

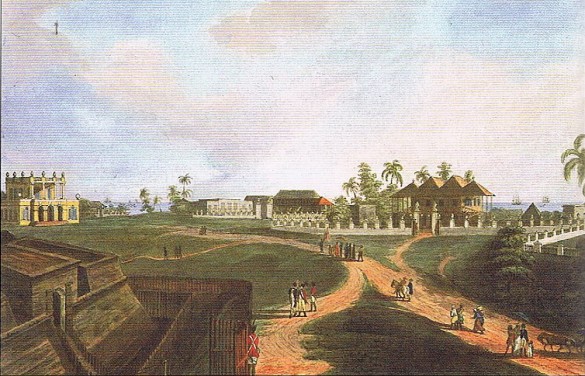

Others sought escape not through the physical act of fleeing, but through alcohol. In 1712 Joseph Collett took charge as governor, overseeing the development of a somewhat more substantial British headquarters called Fort Marlborough. Like so many others, Collett had only come to Bengkulu under duress – he was bankrupt and deemed unemployable elsewhere.

During a single month he and his 19 staff managed to get through 900 bottles of wine, 300 bottles of beer, and 200 gallons of other alcoholic beverages

– prompting appalled East India Company directors back in Britain to wonder “that any of you live six months and that there are not more quarrellings and duellings amongst you”!

There were, however, some who went to Bengkulu by choice.

On 15 July 1756, a young man by the name of Stokeham Donston wrote a letter to his cousin George. He was 23 years old and he was planning to take a post in the service of the British East India Company. “The salary allowed… is about £80 or £90 p. year, but that is nothing in comparison to the advantage made by care and diligence” he wrote – and therein the motivation for so many similar young men of modest fortune throughout the 18th century is revealed. Slack management practices, irregular arrangements, and a whole host of blind eyes turned meant that Company staff in Asia could often accrue enormous fortunes – either through unofficial private enterprise on the side, or through outright corruption.

Young Donston was quite untroubled by horror stories of the Southeast Asian climate: “Some say the climate is unhealthful, and does not agree with the constitutions of the Europeans, but that I believe is in some measure owing to the irregularity of their living… and I fancy it might be avoided by resolution…”

The following year he arrived in Bengkulu, several worlds away from the English Midlands, and in no time at all he realised the full horror of his mistake. Throughout the coming years Stokeham Donston sent letters home by every passing ship, begging every friend and acquaintance to bring whatever influence they might have to bear to get him transferred to India or somewhere else less dreadful than Bengkulu. But to no avail. Sometimes he rallied and revealed his dreams of somehow still making a fortune and returning home to play at being a country gent. In 1765 he wrote again to his cousin in Nottinghamshire:

I want devilishly to make up about £500 p. annum. The lord knows when that will be, it will satisfy my ambition and then you and I will join and keep a Pack of Beagles for the diversion of ourselves and the Worksop Gentry, do you think we can do it?

He never got his beagles, and he never got to go home. A full decade after that letter was mailed, the weary little British community made one of its depressingly regular trips from the fort up the road to the weed-clogged cemetery to inter yet another of their number. The gravestone they set in place is still there: “To the Memory of Stokeham Donston Esq. who departed this Life at Marlbro’ the 2nd April 1775. Aged 41”.

By the beginning of the 19th century Bengkulu was costing the East India Company a guaranteed annual loss of £100,000 – a vast sum in today’s terms. The pepper trade was pathetic, and relations with the locals were always testy. On various occasions over the decades, the British had had to rely on mercenaries from the Bugis community settled in the area to save them from annihilation by put-upon locals, who periodically got fed up with their practices of debt-slavery and forced pepper and coffee production. At one point, in 1719, the British had to flee en masse in boats after angry locals stormed Fort Marlborough, while in 1805 a particularly heavy-handed official, Thomas Parr, was beheaded in his own bedroom by some thoroughly aggrieved Rejang chiefs.

The last but one British chief in Bengkulu was none other than Thomas Stamford Raffles, erstwhile lieutenant-governor of British-ruled Java and future co-founder of the British settlement at Singapore (which he actually established while officially based in Bengkulu). On arrival he declared it “without exception the most wretched place I ever beheld”. During his tenure there, from 1818 to 1824, he made some efforts to knock the place into shape. He declared the remaining 200 African slaves (most of them Bengkulu-born by many generations at that stage) officially “emancipated” and gave them each a printed certificate to that effect. It was the classic grand but ultimately empty gesture: they could hardly go “home” and they remained as the lowliest labourers in government service, their circumstances essentially unchanged – though Raffles’ wife Sophia did pluck an eight-year-old girl from their ranks to serve as her personal household servant, “in order to set an example to the rest of the European community”.

Raffles lost three of his four young children to the Bengkulu climate, and by the time he left his own health was irrevocably broken too. The following year a treaty was signed between Britain and Holland. The former agreed to pull out of its territories in Sumatra, while the latter abandoned all claims on the eastern side of the Straits of Melaka. Colonial Bengkulu was, to all intents and purpose, abandoned. Some found themselves quietly wondering why it had taken 139 years since the receipt of that pitiful letter from Benjamin Bloome and Joshua Charlton for the British East India Company to come to such an eminently sensible decision.

Today Bengkulu is one of the remotest of Indonesia’s provincial capitals; a small city where bougainvillea wells up out of the gardens and a hot breeze blows from the south. Here and there a mildewed monument to a forgotten British resident breaks the modest flow of motorbikes. There is a beach, broad and bright and empty, backed by whispering casuarinas and crooked palms. Fort Marlborough still stands, slices of heavy masonry ringing a sweltering inner compound where rusting cannon lie in the grass like beached seals. But of the older outpost, Fort York, nothing survives but a few indistinct traces of stonework in a tangle of mosquito-troubled vegetation north of town. The cemetery, meanwhile, is a favourite hang-out for local youngsters, who use the cracked tombstones for goalposts. In the evening, when the sun drops, Bukit Barisan still shows to the east like a black wave, and the pale sky overhead fills with thousands of flickering swiftlets. To the west the Indian Ocean melts into a pool of molten copper. You can scan the salty distance until the last of the light is gone, greenish behind the horizon, but there are no ships.