No-one knows when the Chinese first hit what was to become Jakarta. Certainly, when the Dutch first arrived, in 1596, they found Chinese merchants manufacturing arak (rice wine) on the east bank of the river. The land had been granted by Pangeran Wijaya Krama, a local ruler subservient to Banten, the centre of power at the time.

No-one knows when the Chinese first hit what was to become Jakarta. Certainly, when the Dutch first arrived, in 1596, they found Chinese merchants manufacturing arak (rice wine) on the east bank of the river. The land had been granted by Pangeran Wijaya Krama, a local ruler subservient to Banten, the centre of power at the time.

Going back further in time we find court records from the royal cities of Demak and Cirebon hinting that ancestors of the ruling classes had Chinese blood. There is also evidence of trade between the port cities of north Java, such as Surabaya, Gresik and Tuban, and China going back to the 9th Century. 700 years before the Dutch arrived, that’s an awful lot of history waiting to be told.

Like throughout South East Asia, those far-off pioneers set off in search of riches and often never returned. Single men, hard working, they would settle down and marry locally. When they became wealthy they would send money home for their families and always, at the back of their minds, was the notion that one day they would return home. To be buried with their ancestors, their filial duty.

It didn’t always work out that way and by the time the Dutch and other Europeans started poking their prows round the eastern seas, the Chinese were at the heart of a vast maritime trading empire from the coastal cities of India, down the Straits of Malaka, along the north coast of Java, taking in the riches of Siam and along the pirate infested seas off the southern coast of China.

The business was trade, the language in those early days Malay, Farsi, Portuguese but it was the Chinese who opened doors and who spotted markets.

By the 16th Century, Banten was at the centre of this emporium, fat and rich from the proceeds of pepper and spices and the Chinese held the purse strings. Today Banten Lama stands as a silent reminder to those heady, unhealthy days. A Chinese temple stands alongside a cumbersome Dutch fort that once overlooked the busiest port in the east. But now, like the traders and the vagabonds who filled those medieval bazaars, the seas have gone. The ruins of a Sultan’s palace opposite a mosque with its Chinese designed minaret remain a memory of an early Singapore.

At the same time the Chinese settlement by the Ciliwung was a back water, selling arak to sailors who passed through. The area was once where the Pajajaran Empire communicated to the outside world, perhaps the Chinese had seen the river rise and fall in importance, selling intoxication to hardy men setting out on hazardous missions around the eastern waters.

Small it may have been, but the Chinese community was organized and had its own headman, a gent at the time named Watting. The idea of a headman for each community was common throughout the archipelago at that time. Despite what nationalists might try and tell people today, cities, and especially port cities, were as cosmopolitan then as they are now. In the markets of early Banten and Jakarta, Arabs, Gujerats and Europeans would trade while Bugis would ready their ships and Japanese mercenaries stood guard. Each community had its own head man who could settle cases with other groups and generally keep the atmosphere calm and amicable.

Small it may have been, but the Chinese community was organized and had its own headman, a gent at the time named Watting. The idea of a headman for each community was common throughout the archipelago at that time. Despite what nationalists might try and tell people today, cities, and especially port cities, were as cosmopolitan then as they are now. In the markets of early Banten and Jakarta, Arabs, Gujerats and Europeans would trade while Bugis would ready their ships and Japanese mercenaries stood guard. Each community had its own head man who could settle cases with other groups and generally keep the atmosphere calm and amicable.

As Jakarta grew under Dutch influence, so did the Chinese population, but even in the early 17th Century there was resentment at what was perceived to be the Chinese special privileges. Europeans who arrived seeking their fortune found that the Dutch authorities protected the interests of the Dutch East India Company monopoly and they couldn’t get a foot in the mercantile door. The Chinese however, were free to do so and this upset the newcomers who sought their own piece of the pie. In those early years Jakarta, then of course known as Batavia, was considered a Chinese town under Dutch rule.

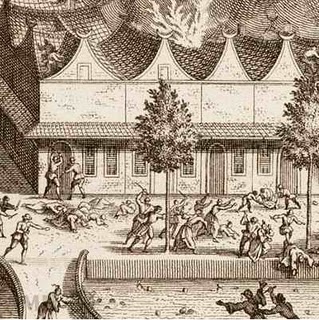

Until 1740 the Chinese flourished as never before. Banten faded and died, trade and money headed east. Masts filled Jakarta bay as ships came to and fro and at the heart of the business were the Chinese. It was their golden era but times of bounty never last. The riots and pogrom of 1740 killed many thousands of Chinese and the rivers ran red. Indeed Angke means just that, Red River, and the name of the river recalls those grim days 267 years ago.