Sulawesi: twice the size of the UK, volcanoes galore, uninhabited islands, strange creatures, boiling seas, electric clams and tons of bioluminescence, all wrapped up in Mother Nature’s blanket of beauty and sustainability.

In January, we planned a dive vacation to Halmahera, but the Gamalama volcanic eruption nixed that in late December. The only positive aspect to the detailed planning and flight expenditures was learning how to spell words like ‘Halmahera, Ternate, Gamalama’ and why we shouldn’t cancel Garuda flights less than 72 hours prior to departure! Once the ash settled and the Ternate airport re-opened, our chartered dive boat was long gone to North Sulawesi, with no return option.

Fate seems to have a way of working out problems here in Indonesia – our flights on Garuda Airlines went without a hitch, with all eight of us arriving to Manado from both Jakarta and Bali by mid-morning. From here, it was an hour’s drive east towards our liveaboard dive boat parked in Lembeh harbour. By 2.30pm we were steaming out in anticipation of our first dive.

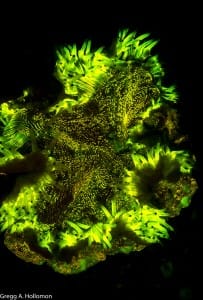

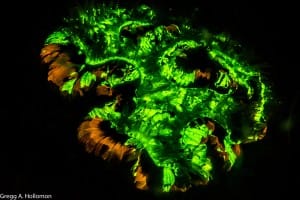

This adventure took us approximately 100 kilometres north of Manado to many volcanic islands. We were fortunate to experience two spectacular night dives, one off the south shore of Bangka Island and the other within Lembeh Strait itself. On these dives I focused on capturing the miraculous marine bioluminescence common to these waters.

This adventure took us approximately 100 kilometres north of Manado to many volcanic islands. We were fortunate to experience two spectacular night dives, one off the south shore of Bangka Island and the other within Lembeh Strait itself. On these dives I focused on capturing the miraculous marine bioluminescence common to these waters.

Most people have experienced luminescence of microscopic phytoplankton but what I am discussing is the actual light output from higher marine organisms such as corals, anemone and small critters when subjected to (or excited by) a spectrum of blue light. There have been a number of research articles written on this subject, but no one yet understands the real background purpose of animals exhibiting bioluminescence. Postulation focuses on defence mechanism (to confuse predators), reproduction (to attract a mate) or to attract prey. Communication may be a primary purpose for the deep sea creatures.

Bioluminescence is the world’s most efficient method of light production. Most of the light emitted is green, blue or reddish in colour. These are the wavelength colours which best penetrate sea water. Some of these organisms don’t actually fluoresce themselves but result from symbiotic hosts such as luminescent bacteria and/or algae (as in the case of coral). Researchers have studied marine luminescence since the early 1900s.

Method to View and Photograph Marine Bioluminescence

First of all, please keep in mind that bioluminescence is not phosphorescence. Phosphorescence is a release of light from oxidizing crystals which are activated by light or radiation, while bioluminescence is a complex chemical response which releases light when excited. Bioluminescence is highly evolved in the marine world but normally goes unnoticed, as the light emitted cannot compete with sunlight or a strong underwater torch.

The equipment you need to scan for luminescent subjects is a dive light with either a UV option or with a blue filter placed over the lens. A better alternative is to apply a blue gel filter over your dive light and look through a yellow filter placed either over your mask or in a small frame. The yellow filter cancels the blue light but allows the luminescence to shine through. What you see using this method are only the luminescing subjects, while everything else will be completely dark.

I use an i-Torch Pro-6 with the UV light option while diving to scan for subjects. The ultraviolet spectrum is not the best wavelength to ‘excite’, but it works fairly well as a screening tool. Fortunately, the UV lights up the surrounding area, making for a more comfortable night dive. Either method you use, try and divorce yourself slightly from the rest of your dive group (with their 2,000 lumen dive lights) in order to view these subtleties. Just enjoy the calm because you are basically swimming around in the dark except for these glowing creatures.

I use an i-Torch Pro-6 with the UV light option while diving to scan for subjects. The ultraviolet spectrum is not the best wavelength to ‘excite’, but it works fairly well as a screening tool. Fortunately, the UV lights up the surrounding area, making for a more comfortable night dive. Either method you use, try and divorce yourself slightly from the rest of your dive group (with their 2,000 lumen dive lights) in order to view these subtleties. Just enjoy the calm because you are basically swimming around in the dark except for these glowing creatures.

To photograph subjects, you will need to attach a blue filter assembly over your flash or strobe and a yellow filter over the lens of the camera. You can make this or if you are lazy, like me, just purchase a NIGHTSEA Fluorescence Excitation Filter which screws into the front of the strobe. This commercially available filter screens out all light except that of the 510 nanometre wavelength. You will also need a yellow filter on the camera lens.

Once a critter or coral shows up as ‘popping’, come in close to compose the picture. It is best to have your dive buddy hold the UV or blue-filtered dive light on the subject to get a good focus. I use the focusing light on my fancy strobe for this. It is best to use a fairly high ISO camera setting (800-1,500), as the blue filter absorbs much of the light from the strobe. I use a 60mm macro lens for this purpose. Shoot manual if your camera allows. Experiment a little and take multiple bracket shots to get the best exposure. Have fun!

Rule number one is not to lose your dive buddy (wife) as you diddle around. No matter how great your picture is, it’s not worth it. Instead, dive together and have her take the shot!

____

FAST FACTS: Sitaro Islands Regency

Province: North Sulawesi Province

Land size: 275.96 km2

Population: 63,543 (2010)

How to get there: Daily flights from Jakarta to Manado with Garuda Airlines and Lion Air.

Where to stay: Liveaboards and land accommodation available in Lembeh Strait. Just search online.

What to do: Diving, snorkelling, beach combing, volcano climbing and sightseeing.