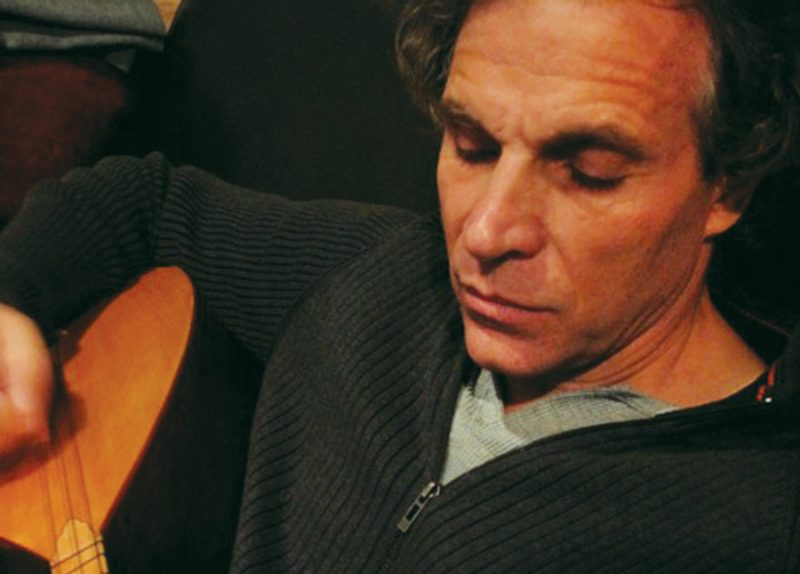

Author and co-author of more than 20 books and numerous articles on Indonesian art, culture and history, Bruce W. Carpenter is considered a leading expert in the field of Indonesian studies. His publications include Willem G. Hofker, Painter of Bali (1994), W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp First European Artist in Bali (1997), Batak Sculpture (2007), Ethnic Art of Indonesia (2010), Gold Jewellery of the Indonesian Archipelago (2011), Nias Sculpture (2013), Lempad of Bali, the Illuminating Line (2014) and Indonesian Tribal Art (2015).

Can you tell us how and why you landed in Indonesia?

My first Indonesian experience was at the New York World’s Fair in 1964. As an imaginative young boy I was mesmerized by the spectacular Indonesian pavilion, the construction of which had been personally overseen by Sukarno, the first president. I didn’t understand much but I knew I wanted to go there.

That opportunity arose in the 1970s after university. Nobody had bothered to tell me that the purpose of going to school was to earn a living so I had studied oriental art and history. Unemployable and adventurous I headed to Amsterdam, where I had my second meeting with Indonesia at the Tropical Museum. As a second winter came around I decided to flee the northern climes and headed east based on tips provided by early travellers on the hippie trail that led to Bali, where I landed in 1975.

Tell me about your early travels in the archipelago.

After a sojourn in Thailand and Malaysia I took a boat to Medan and immediately headed up to Prapat on the shores of Lake Toba. I arrived on full moon night and was amazed to hear Batak singers belting out a variety of tunes that echoed across the waters in splendid harmony. In the following year I would voyage to Java, Bali, Borneo, Sulawesi, the Lesser Sundas and beyond.

Bali was the penultimate sanctuary – a place of beauty, grace and rest. As thousands before, and millions after, I was smitten by the romance and fell head over heels. It is hard to believe that there was no electricity outside of Denpasar. Up until around 1994, communications with the outside world were abominable.

How and why did you start writing?

My grandfather was a high professor at Cambridge University who was a leading authority of Middle Eastern culture and languages. I much admired him and hoped to follow in his footsteps, although my career as a hippie took me off the usual track. My first book co-authored with Dr. Denny Thong and Stanley Krippner was about Balinese traditional healing. Stanley and I actually wrote an article on analyzing Balinese dreams that was published in the magazine Shaman’s Drum, which later included one of Robin Lim’s articles.

Trained in art history I was aghast that so little was being published about Indonesian art and artists. I actually researched my book on W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp next, although it was published later. In the process I met Maria Hofker, the widow of Dutch artist, Willem. Friends of Rudolf Bonnet and Walter Spies, they had lived a remarkable life in Bali from 1938-1942, which abruptly and tragically ended with the Japanese invasion. She invited me to author a book on her husband. It was a great success. I would also like to believe it played a key role in the remarkable prices achieved by Hofker paintings today.

With time I turned to my true love, Indonesian art, producing an average of one book every year or two.

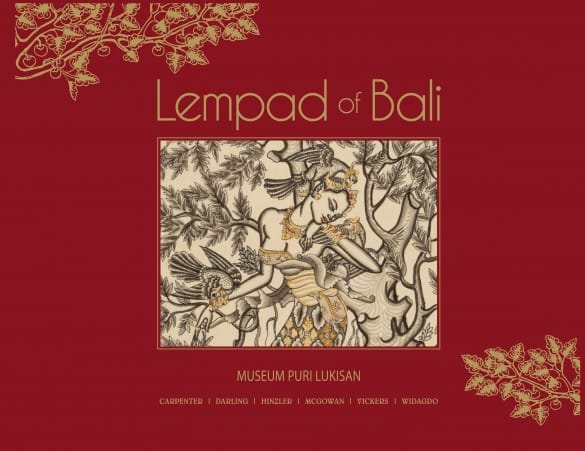

Lempad of Bali took many years to accomplish. What were some of the challenges inherent in the development of this massive and comprehensive tome on this master of traditional art?

I visited Lempad during my first trip and eventually become a close friend of his eldest son, I Gusti Made Simung, who I, along with numerous other expatriates, considered a brilliant and humorous mentor of all things Balinese. All of us spoke of the need for a book and expected John Darling to accomplish this task.

This early idea would only begin taking shape around 2006 at the time of the 50th anniversary of the Museum Puri Lukisan, when I was asked by Soemantri Widagdo to help with a large retrospective exhibition and catalogue. It took us years to track down hundreds of his paintings, which had been scattered around the world. As the art director, project manager and co-author – with five other noted experts – I would like to think of it as a gift to the Balinese people for all they have given me.

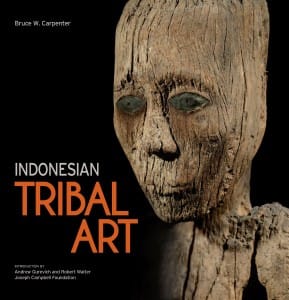

What about your latest book – Indonesian Tribal Art?

One of the most exciting developments in the last decade is the discovery that the history of art in Indonesia is far older than ever imagined. The best example is the discovery that prehistoric cave paintings in Sulawesi once thought to be 1,500 to 2,500 years old, are in fact 38,000 to 40,000 years of age. Not only is Indonesia – along with the Alta Mira and Lascaux caves – home to some of the earliest art in the world, this discovery is only the tip of the iceberg because thousands of cliff and cave paintings can be found throughout the archipelago. This and many other exciting discoveries are discussed in my latest book Indonesian Tribal Art, which also has a stimulating introduction written by the Joseph Campbell Foundation.

How do you see contemporary Indonesian artists expressing modern issues while honouring their historical cultures?

For a large part colonialism shattered the connection between ancient and profound art traditions and modern and contemporary art. Shockingly, numerous Indonesian artists believe that real art came from the West! One of the great challenges is to reconnect them with their own great tradition. The process has already begun but is often plagued by superficial flourishes – the random inclusion of wayang puppets or other traditional icons – that lack conviction and depth. Unfortunately, as everywhere, the art market here is driven by commercialism, and with a few exceptions is not interested in the broader implications of Indonesian art history and how it relates to contemporary art.

Why is an awareness of the historical art and culture of Indonesia important to future generations?

Indonesia’s greatest asset is its youth. Creativity abounds everywhere in spite of the dysfunctional nature of the political system and infrastructure. I trust they will find a way forward. One of my biggest complaints to young Indonesians is that they should begin appreciating, studying and writing about their own art, culture and history.

What are your plans to continue sharing the history and art of Indonesia with the global community?

Indonesia is one of the world’s greatest reservoirs of design and creativity. China may be able to mass-produce things cheaper but Indonesia brings another dimension that mirrors the souls of these remarkable people. One of my biggest apprehensions is the failure of many to understand that the tragedy of poverty is not limited to food, water and clothing alone but also to pride and identity.

A people can achieve a modicum of prosperity but if you strip them of their history and art you have committed a wrong comparable to stealing their souls.

Unfortunately, the amount of money made available for the preservation of culture is limited, often inconstant and distributed by those with definite cultural prejudices with the so-called ‘refined’ traditions getting the big money. There is also little sense of philanthropy in Indonesia; national and local museums receive limited funding and are viewed as boring and old fashioned. Private museums are inevitably vanity projects that often collapse because of unprofessional management, indifferent collections and lack of funding. The greatest museum in Bali founded in the 1930s is in Denpasar but is little known and in dire need of restoration and dynamic stewardship.

Billions are spent on sports and other mass events but getting a grant to produce a book or study of a fast disappearing unique art form is a near impossible task. My hope is to stimulate appreciation and consciousness of the value of these fragile traditions, many of which have already disappeared.