If I were to ask you, who Stamford Raffles was, you would most likely answer: the founder of Singapore.

In fact, I have asked this question on several occasions and apart from the answer mentioned, I also got answers such as: the founder of the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, and, the chap who concocted the Singapore Sling! Obviously not everyone is equally interested in, or knowledgeable about history. Whatever, at least the answers were related to Singapore.

Raffles certainly put his stamp on Singapore, but interestingly, he visited the place only three times: for nine days in January and February of 1819, about four weeks in May to June of the same year, and for eight months from October 1822 to June 1823. The real founding, that is the hard day to day work of planning and building, of consulting and deciding, was done by the first two British Residents: Farquhar (1819-23) and Crawfurd (1823-6). Farquhar worked with the Malay rulers to secure the survival and growth of the British settlement on Singapore Island, while John Crawfurd, another Scotsman, actually made Singapore British, by signing the Anglo-Malay treaty of August 1824, by which Sultan Hussein and Temenggong (Malay title of nobility, usually given to the chief of public security) Abdul-Rahman ceded the Island to the British. Farquhar and Crawfurd have slipped into oblivion, whereas Raffles has remained in the limelight. Most of us do of course like a Singapore Sling.

But in this article I want to draw your attention to another Raffles, that is, Raffles the Lieutenant-Governor of Java, a position he held from September 1811 to March 1816, and Raffles the writer of the magnificent opus The History of Java, published in 1817.

From both a governmental and a social-anthropological point of view he was a highly successful administrator. He increased the revenue eightfold by removing restrictions on trade and shipping, while reducing port fees. And he stimulated greater local participation by removing the fetters imposed on intercourse with the Javanese by Dutch officialdom. In stark contrast to the Dutch approach, his administration aimed, in his own words, at being “not only without fear, but without reproach.”

He was a man of vision. He abhorred the colonial attitudes and opinions displayed by the Dutch colonialism, that is the Dutch rulers in the Netherlands East Indies. Raffles, in his History of Java, starts the Introduction by clarifying that …severe strictures passed, in the course of this work, upon the Dutch Administration in Java, … may, for want of careful restriction in the words employed, appear to extend to the Dutch nation and character generally… He then explicitly declares: that such observations are intended exclusively to apply to the Colonial Government and it Officers. The orders of the Dutch Government in Holland to the Authorities at Batavia, as far as my information extends, breathe a spirit of liberality and benevolence; and I have reason to believe, that the tyranny and rapacity of its colonial officers, created no less indignation in Holland than in other countries of Europe.

This is the opening paragraph, and in the hundreds of subsequent pages, Raffles does indeed severely criticise, and disagree with the Dutch colonial government and officers. He also shows a great affinity and admiration for the Javanese—the “Javans”, as he refers to them—their behaviour, conduct, and moral character. They are easy and courteous, and respectful even to timidity; they have a great sense of propriety and are never rude or abrupt.

His observations were, however, not lacking criticism where such was warranted. Those of higher rank, those employed about court or administering to the pleasure or luxuries of the great, those collected into the capital or engaged in public service, are frequently profligate and corrupt, exhibiting many of the vices of civilisation without its refinement, and the ignorance and deficiencies of a rude state without its simplicity. The people in the neighbourhood of Batavia are the worst in the island, and the long intercourse with strangers has been almost equally fatal to the morals of the lower part of Bantam. He clearly blames the foreign influences for this behaviour. …but the farther they are removed from European influence and foreign intercourse, the better are the morals and the happier are the people. (The History of Java, p. 247/248)

I am convinced that Raffles was equally liked by the Javans, too. How could he otherwise have acquired the enormous amount of data, information and local knowledge about the island, its people, customs, lifestyles, artefacts, antiquities, flora, fauna, in a period of a mere four-and-half years. Of course, quite a lot of the information compiled for the History had already been collected by other scientists and surveyors. But, in 1814, information conveyed to him personally by local Javanese, led to the discovery of Borobudur. Local common Javanese, mind you, a village chief, perhaps, who obviously was allowed into his presence and who, even more importantly, felt sufficiently at ease to talk to him. The Dutch had had a presence in Semarang for at least 200 years and the temple ruins had been there for many more, but never had information about its existence been relayed to the colonial masters. And if it had, they might have been utterly uninterested, focussed as they were on making money.

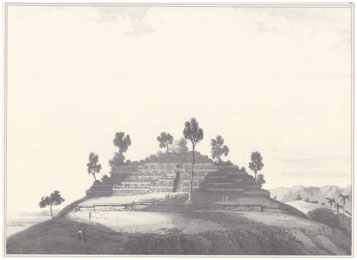

The Plates to Raffles’s History of Java, published in 1830 as a separate volume accompanying the second edition of the History, contains many illustrations relating to Borobudur, or Boro Bodor in Raffles’ words. The first of these is Plan of the Great Peramidal (sic) Temple called Boro Bodor in the Kedu district Java.

The Temple of Boro Bodor, Plates to Raffles’s History of Java

Remember, in 1814 this was a crumbling ruin overgrown with shrubs and trees. Raffles, not able to investigate the site himself, sent H.C. Cornelius, a Dutch engineer, who with 200 helpers in two months cleared away vegetation and earth to reveal the monument. The Plan is likely part of Cornelius’ report to Raffles and contains details such as the measurements, the number of steps leading to the terraces, the number of stupas and the like.

Remember, in 1814 this was a crumbling ruin overgrown with shrubs and trees. Raffles, not able to investigate the site himself, sent H.C. Cornelius, a Dutch engineer, who with 200 helpers in two months cleared away vegetation and earth to reveal the monument. The Plan is likely part of Cornelius’ report to Raffles and contains details such as the measurements, the number of steps leading to the terraces, the number of stupas and the like.

Not only is the Borobudur covered in great detail in the Plates to the History, nearly every aspect of life on Java is dealt with in detail: farm implements, equipment such as a spinning wheel and weaving loom, and tools for batik printing, carpenters’ tools, Javanese weapons and krises, ancient forms of the Javanese alphabet, musical instruments, signs representing the pasar or market days, and engravings of the Prambanan and temples on the Dieng Plateau, reproductions of inscriptions on stone at Kevali (near Cirebon) and on a stone called Batu Tulis. Of outstanding quality are the aquatint engravings of Javanese costumes by William Daniell. These include a Javanese of the lower class, a Javanese chief in ordinary dress, a Javanese in war dress and in court dress, a Madurese of the rank of mantri, and finally a Papua boy, Dick, who came into Raffles’s service in Bali and was brought to England by him in 1816. A fold-out map of Java completes the Plates.

The book was in its time not a great commercial success, of the 1,500 copies printed for the second edition, only some 500 were sold. While at the time insufficiently valued, nowadays it is extremely useful and invaluable as a window on Java of 200 years ago. It has in its integrated completeness never been equalled.

References:

• The History of Java, Thomas Stamford Raffles, Oxford University Press, 1988

• Raffles Revisited: A Review & Reassessment of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781-1826) by Ernest C. T. Chew, Associate Professor of History, National University of Singapore

• Wikipedia