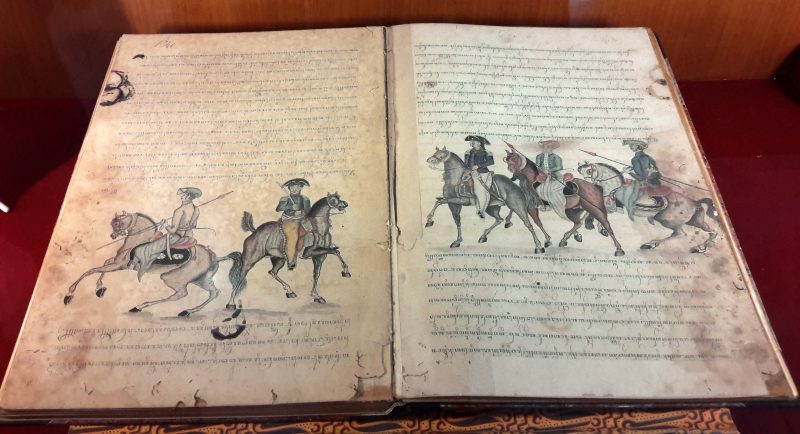

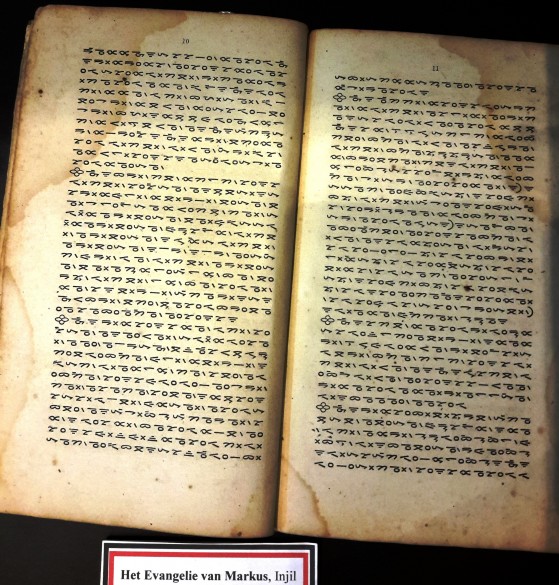

Mehamat Boru Karo Sekalu, a lady working in North Sumatra Museum reads an ancient book written in Batak letters, eloquently. The visitors of Nusantara Old Manuscripts Festival in Taman Mini Indonesia Indah on 21 April 2017 watched her in awe. “This is a Bible book of 1867, printed in Amsterdam, using Batak alphabet. There are five tribes in Batak, and each has their own letter, a bit different from each other.” When asked whether she can read and write in all of them, she replied: “Yes, of course. I work in a museum with 250 old manuscripts. Those manuscripts narrate prophecy, medicine, almanac, spell, etc.” She joked: “If you need to charm someone, come to me!”

Advanced civilization is marked by the emergence of alphabets as a way to express ideas, values, and norms in the society. The discovery of Yupa inscription of Kutai Kingdom in East Kalimantan and 7 other inscriptions of Tarumanegara Kingdom in West Java region in the 5th century concluded the end of Indonesia’s prehistoric era. Trading and sailing with other nations encouraged alphabets introduction to Indonesia.

In the first millennia India’s influence manifested in the usage of Pallawa letter; Arabic was introduced around 16th century after the fall of Majapahit Empire and Latin was known through Western colonialization later on. Local people did not absorb the influences completely but they incorporated them with their local values and cultures, resulting in new variation of letters.

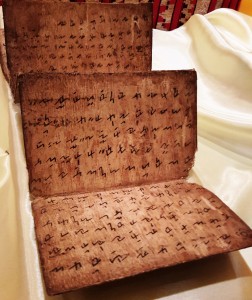

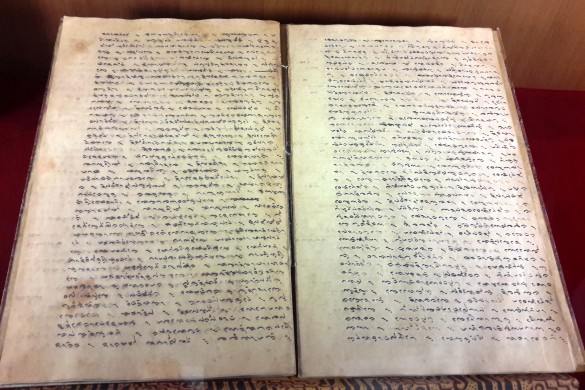

There’s difference between inscription and manuscript. Inscription was written on a long lasting media such as stones and copper plates. Being more difficult to replicate, there is no two similar inscriptions. An inscription initiator was usually a king or authorities. An inscription bears no writer name on it. Meanwhile manuscripts were written on relatively short-lived materials like bamboo, palm leaves, wood bark and papers, daluang (thin sheet made of broussonetia papyrifera wood bark), etc. As such, manuscripts ever discovered in Indonesia are much younger. In manuscript, there is a tradition of duplicating, sometimes the writer’s name was mentioned, and the initiator was not always the authorities.

Indonesia’s Law Number 43 Year 2007 states that old manuscript is a hand-written document made on transitory, perishable materials; at least 50 years old, not duplicated by any other way and exist either in Indonesia or abroad.

Henri Chambert-Loir and Oman Fathurrahman stated in 1999 that Indonesia owns more than 58,000 manuscripts written in local letters. Hurip Danu Ismadi, from the Department of Education and Culture as cited by Kompas on 20 January 2017 states that there are 12 local alphabets in Indonesia: Javanese, Balinese, Old Sundanese, Buginese/Lontara, Rejang, Lampung, Karo, Pakpak, Simalungun, Toba, Mandailing, and Kerinci/Rencong.

Dewaki Kramadibrata, Lecturer of Literature Department, the Faculty of Culture, University of Indonesia explained that Indonesian manuscripts can be found, among others, in Sumatera (Palembang, Bengkulu, Riau, Lampung), Java (Jakarta, Banten, Cirebon, Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Gresik), Madura, Bali, Sumbawa, Bima, Ternate, Tidore, and Ambon and used local languages such as Acehnese, Malayan, old Sundanese and Javanese, Madurese, Sangir, Arabic, Dutch, etc. Themes of these manuscripts are stories of solace, faith and belief, history, customs and tradition, genealogy of royals, law, architecture, medicine and healing, Islamic teachings, agreements and others.

According to Munawar Holil, lecturer of the Faculty of Culture, University of Indonesia, the Indonesian oldest manuscript is Kakawin Ramayana in Old Javanese language of 9th century. Indonesia has great poets and authors like Mpu Kanwa who composed Arjunawiwaha in 11th century, Mpu Sedah and Mpu Panuluh who wrote Kakawin Bhratayudha in the 12th century. Kakawin Sutasoma written by Mpu Tantular in the 14th Century contained Bhinneka Tunggal Ika which means ‘Although in pieces, yet One’ which is now Indonesia’s motto.

Several manuscripts are recognized by UNESCO as Memory of the World: Negarakretagama also known as Desawarnana composed by Mpu Prapanca in 14th century, containing the depiction of Majapahit Kingdom during its golden time; Diponegoro Chronicles; archives of the Dutch East India Company; and Sureq Galigo or La Galigo, a myth of creation based on oral tradition and was written down from 13th – 15th century in Buginese. With 6,000 pages, La Galigo becomes the longest literature in the world.

Old manuscripts are important not only in the manuscripts per se, but also in their contents. They give accurate description about culture, history, knowledge, local wisdom as well as the development of language and letters of that time.

Aditia Gunawan, an old Sundanese and old Javanese philologist from Indonesian National Library said during Indonesian Old Manuscript seminar on 21 April 2017 in TMII that Indonesia’s old manuscripts are scattered in many countries: The Netherlands has 17,000 with many of them masterpieces, most likely due to its long colonization in Indonesia. Other countries like the United States, France, Germany, Spain, Norway, Ireland, Portugal, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and even South Africa keep the manuscripts. Indonesia has more than 33,000 pieces dispersed in local museums and other places. In England around 1,200 pieces are stored in British Library since 17th century, meticulously inventoried by M.C. Ricklefs dan P. Voorhoeve.

The spreading was caused by trading, collection by authorities and brought abroad by Indonesians. Most manuscripts abroad are better preserved compared to their cousins in Indonesia; the reasons could be financial issue or ignorance on storage.

Luckily some people and organizations are still taking care of these valuable manuscripts. MANASSA (The Indonesian Association of Nusantara Manuscripts) was established on July 1996 to preserve and study Indonesian manuscripts. Anyone interested in Indonesian manuscripts can join MANASSA in one of its 17 branches. The National Archives of Indonesia on 7, Ampera Raya Street in Jakarta stores and rehabilitates old manuscripts and it welcomes visitors to see their work. The Indonesian National Library on 28A Salemba Raya Street in Jakarta stores more than 10,000 pieces.

“The oldest script stored by the library is Arjunawiwaha written on palm leaves,” librarian Budi Wahyono admitted. The library runs Nusantara Manuscript Festival every year, either in Jakarta or in the location where manuscripts originate.

University of Indonesia and Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University in Jakarta, Padjadjaran University in Bandung, Udayana University in Denpasar, Sriwijaya University in Palembang, and Hasanuddin University in Makassar have studies on manuscripts.

Dwi Mahendra Putra from Denpasar, Bali masters old manuscripts duplication. He often works for the Indonesian National Library and other institutions. He writes and reads old alphabets such as Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, Budo/Merapi Merbabu as well as new types like Javanese hanacaraka, Sundanese cacarakan and others. “I have duplicated masterpieces like Kakawin Arjunawiwaha, Boma Kawya, Gita Sinangsaya and several other manuscripts. It takes about three to five months to duplicate one piece. Meanwhile a lontar or palm leaf needs a really long process before ready for writing: selecting, boiling, immersing, pressing, perforating and lining. At least it takes one year for a fresh leaf from a tree to the writing table. The longer the preparation, the better quality the leaf becomes,” he said. Mahendra is happy to share his knowledge on palm leaf writing. He is contactable at [email protected].