The islands of Java and Bali located 8 degrees south of the Equator in the Indian Ocean are two of the 17,000 islands that make up the Republic of Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelago and the fourth most populous nation on Earth.

The archipelago is also home to the fabled Spice Islands of the Moluccas, the quest for which provided the major stimulus for the great voyages of discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries. To reach these small and remote islands, explorers and merchant adventurers would invariably call first at Java to replenish food and water supplies after the long haul across the Indian Ocean from the Cape of Good Hope, and to pick up local pilots to guide them through the maze of islands between Java and the Moluccas.

Prior to the arrival of the European merchant adventurers and explorers in the region, Javanese merchants on the strategically located island of Java had traded spices and other tropical products with merchants from China, Japan, India, Persia and the countries of the Middle East for centuries. Documentary and archaeological evidence of trade between these countries and the medieval Majapahit Hindu empires of Java and Sumatra, and with the later Muslim Sultanates of the fifteenth and sixteenth century abounds. Java was well known to both Chinese and Indian chroniclers from the beginning of the millennium. Javanese ports such as Banten and Sunda Kelapa (modern-day Jakarta) , which commanded strategic trades routes between east and west through the Sunda Straits, were used by Hindu merchants as provisioning centres en route to China.

It was only in the 16th century that maps of Java began to appear in European books on exploration and in atlases and collections of sea charts, since there was no tradition of map or chart making in the orient outside China. Even in China, mapping was confined to the interior of the country for purposes of taxation and military conquest. Despite the high degree of quantification on Chinese maps, the Chinese still believed in a flat Earth a millennium after the Greek geographer Ptolemy constructed his world map based on the concept of a spherical Earth and the obliquity of the elliptic.

The initial attempts to map the island of Java were crude and generally showed an island of oval shape that was disproportionately broad and with a completely unknown southern coastline.

This was not surprising given the inhospitable nature of the southern coast where the stormy Southern Ocean plunged to great depths in the Java Trench only a few kilometres offshore and where natural harbours were few and far between.

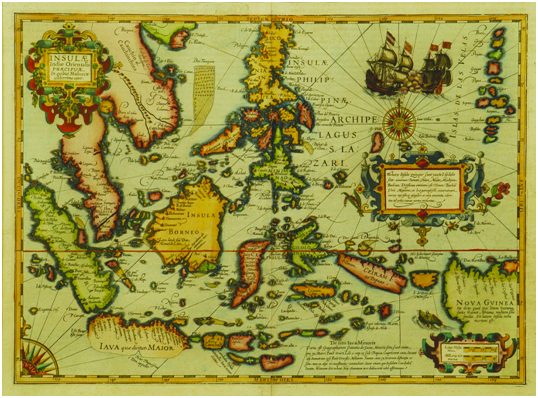

A very famous early 17th century (1606) map of Southeast Asia and the Indonesian islands shows where Francis Drake (Dra. Appulit), the English seafarer and privateer (pirate), called into one of the few ports on the South Java Coast (Cilacap) in 1580 to resupply his ship, the ‘Golden Hind’, on his way back to Plymouth from his circumnavigation of the globe between 1578 and 1580. Drake became the first captain of an expedition of any nation to complete a circumnavigation of the world. The first circumnavigation took place between 1519 and 1521 with an expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese navigator in the employment of the Spanish crown. Unfortunately, Magellan was killed in a skirmish on the island of Cebu in the Philippines in 1521 and his first officer, Jan Sebastian Del Cano assumed command. He and one ship, the Victoria, reached Spain with a surviving crew of 18, in September 1522, three years after the five-ship expedition set out thus completing the first circumnavigation of the world. Drake’s voyage was 56 years later.

Abraham Ortelius’ iconic map of Southeast Asia first published in 1570 in Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, the world’s first uniformly sized atlas, shows Java as it was to appear until the early 17th century. This bloated shape with an effectively blank southern coast was repeated in regional and individual maps of the island until well into the 17th century. In contrast, the north coast facing the shallow Java Sea has numerous ports that have served as trade centres for centuries and hence the coastline was mapped to a reasonable degree of accuracy. However, it was not until the 1630s that the true shape of Java was depicted on the maps of Southeast Asia by Blaeu and Jansson, two great rivals in the atlas trade. Both Blaeu and Jansson depict a narrower, more proportioned and recognizable Java on their regional maps of Southeast Asia and Jansson went further and produced a large-scale map of the island in 1657 in his five-volume sea atlas Atlantis Majoris Quinta Pars Orbem Maritimum.

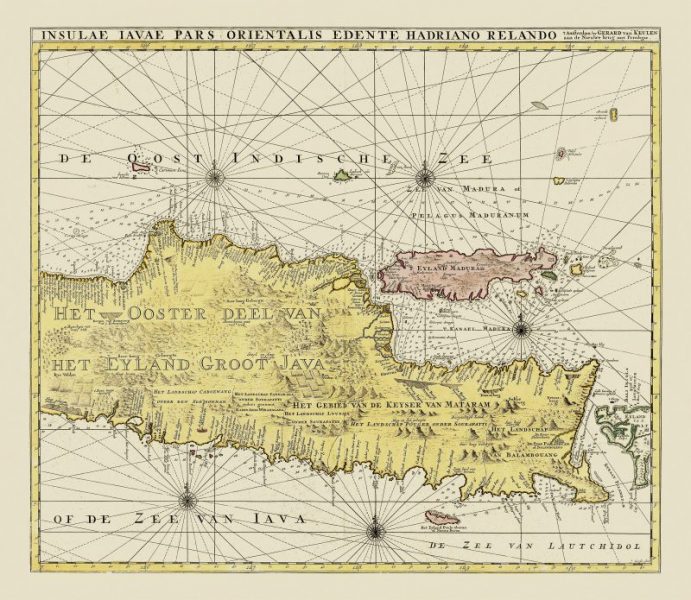

Throughout the remainder of the 17th century and through to the 18th century, the mapping of Java improved, especially the portrayal of the southern coastline culminating in one of the most beautiful, rare and sought-after maps of the island, Johann van Keulen’s large scale map of west and east Java entitled Insulae Iavae Pars Occidentale and Pars Orientale (shown below), on two separate plates that were frequently joined to make one map of the island that was published in the early 18th century. A more well-known version of the same map with insets of Batavia and a coastal profile from the Roads of Batavia appeared in Van Keulen’s Zee-Fakkel, Part V in 1728.

In contrast to Java, the mapping of the adjacent island of Bali, Indonesia’s primary tourist location in the 21st century, remained stuck in the 16th century with a map of the island produced by William Lodewijcksz, a member of Cornelis de Houtman’s pioneering voyage to the East Indies in 1595-97. Later maps of Bali such as François Valentyn’s Kaart van Het Eyland Bali published in 1726 in Part II of Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën – his eight-volume history of the East Indies – contains little new cartographic information, but then Bali was still a Hindu kingdom and not a major part of the Dutch and Javanese trading empire.

Do you want to know more? Please visit Bartele Gallery at Hotel Indonesia Kempinski Jakarta.