In Indonesia, Mother’s Day is celebrated on 22 December. Although it is neither a major celebration nor part of the nation’s culture, many consider this occasion a good opportunity to express their love and appreciation to the women who raised them, in particular to those who contributed to society in general.

In terms of Indonesia’s history, one of the heroines originating from West Sumatra that has not received adequate recognition from the government for what she has achieved is Roehana Koeddoes. Until now, except by the local government of West Sumatra, respect for Roehana—who made a large contribution to improving the standard of social life, enhancing economic welfare and raising political consciousness of the nation—has been contemptible.

Roehana was born on 20 December 1884 in Koto Gadang, West Sumatra. Her father was Muhammad Rashad, a Dutch government employee, and her mother was Kiam. She had five siblings and nineteen stepbrothers and sisters. One of her stepbrothers was Sutan Syahrir, Indonesia’s first prime minister.

Almost all the authors who have written about Roehana link her to education. While Taufik Abdullah named her “the pioneer of women’s education in Minangkabau” (1973), other writers—Tamar Djaja (1980), Jeffrey A. Hadler (2001) and Fitriyanti (2001)—called her the first female educator in Minangkabau.

Almost all the authors who have written about Roehana link her to education. While Taufik Abdullah named her “the pioneer of women’s education in Minangkabau” (1973), other writers—Tamar Djaja (1980), Jeffrey A. Hadler (2001) and Fitriyanti (2001)—called her the first female educator in Minangkabau.

Fitriyanti’s work, Roehana Koeddoes: Tokoh Pendidik dan Jurnalis Perempuan Pertama Sumatera (Roehana Koeddoes: Sumatran First Female Educator and Journalist), published by Jurnal Perempuan in 2001, is regarded as the most complete biography of Roehana ever written.

Various titles proposed by the different authors are no exaggeration. Roehana could indeed be regarded as a figure who had a major role in education-oriented reforms during her time. Not only that, she is the founder of the first school specifically intended to educate women, an institution that had been previously unavailable in this country.

There have been a number of schools in West Sumatra when Roehana began teaching, but they were generally established by the government or certain institutions, which were aimed at educating male children. In addition, students graduating from the schools tended to work for government agencies and relied on other people or institutions. In contrast, Roehana oriented her school towards enlightening and creating self-reliant women.

Roehana began to plunge into the world of education at a very young age. When she was seven years old, she provided her female friends with new information and knowledge by reading newspapers aloud before them. Roehana was talented at reading, since her father always brought Berita Ketjil home, a newspaper published in Medan. One year later, she started teaching her friends how to read and write. Though this activity seemed simple, for a time marked by darkness of information Roehana’s small step had tremendous meaning to people.

Her important breakthrough was made as she established Keradjinan Amai Setia on February 11, 1911 in Koto Gadang. This association had more than 60 erudite women whose goal was to advance various aspects of women’s lives in Koto Gadang to achieve glory of the whole nation. It further set up a school of the same name, which equipped its students with handicraft-making for women, reading and writing Arabic and Latin alphabets for elementary school level, spiritual and moral teaching, and housekeeping (child care and cooking).

Later on, Roehana moved to Bukittinggi city and founded a new school, Roehana School. What made the new school different from her previous one was that in addition to giving literacy subject matters (Latin and Arabic), Roehana School provided its students with more practical skills like sewing.

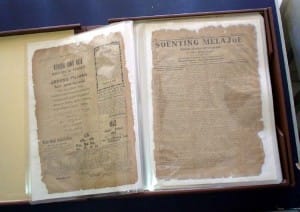

Roehana is also identified by her strong link to the press. Tamar Djaja (1956) named her “the first journalist in Indonesia”, while Hadler (2001) considered her “the first female journalist in Minangkabau”. Granted, Roehana did have a big share in local and national press. She was a pioneer in the publication of a newspaper by and for women called Soenting Melajoe. She even became its editor and wrote for it on a regular basis. There were at least two articles of hers published in each issue for nine years.

Most of Soenting readers were women. In one of its editions, 24 of its 35 customers were known to be women. More interestingly, almost half of those customers resided outside West Sumatra in Bengkulu, Palembang, Tapanuli, East Sumatra, Aceh and Java.

Soenting Melajoe played a role in fighting against Minangkabau’s male domination. This role was highly visible from the various articles made by Roehana and other contributors in the post 1914 editions, suggesting many Minangkabau male authorities had emasculated women’s rights. Furthermore, the paper helped spread the use of Malay among Minang women. This constituted Soenting’s great achievements, following soaring trends of educated Minang women speaking Dutch.

Soenting Melajoe played a role in fighting against Minangkabau’s male domination. This role was highly visible from the various articles made by Roehana and other contributors in the post 1914 editions, suggesting many Minangkabau male authorities had emasculated women’s rights. Furthermore, the paper helped spread the use of Malay among Minang women. This constituted Soenting’s great achievements, following soaring trends of educated Minang women speaking Dutch.

Equally important, Soenting had also inspired the birth of another women’s newspaper, among others Soeara Perempoean (1919) and Asjraq (1925). Unlike Soenting, which heeded women to stay at home, the two papers paid attention to different segments of women. While schoolgirls were interested in Soeara Perempoean, a lot of women’s associations were more attracted to Asjraq, since it attempted to combine form and spirit of both Soenting Melajoe and Soeara Perempoean.

In addition to engaging in publishing Soenting Melajoe, Roehana got involved in publishing several other newspapers; Perempoean Bergerak in Medan with Siti Satiaman and Parada Harahap and Radio in Padang. Some of Roehana’s writings got published in other newspapers in Sumatra and Java.

Kompas daily named Roehana “A women who revealed the world” on August 5, 2013, while historian Taufik Zahren categorized Roehana as one of the nation’s ladies in his book, 7 Ibu Bangsa (7 Nation’s Ladies). Fitriyanti Dahlia, the author of Roehana’s biography, really expects that Roehana’s life story be adapted to motion picture in view of her amazing contribution to this country.

Unfortunately, she is yet to receive recognition from the central government, say by appointment as a national hero. She deserves more credit for what she has done. History books show that she has actually done much for the advancement of her people, region and the nation.