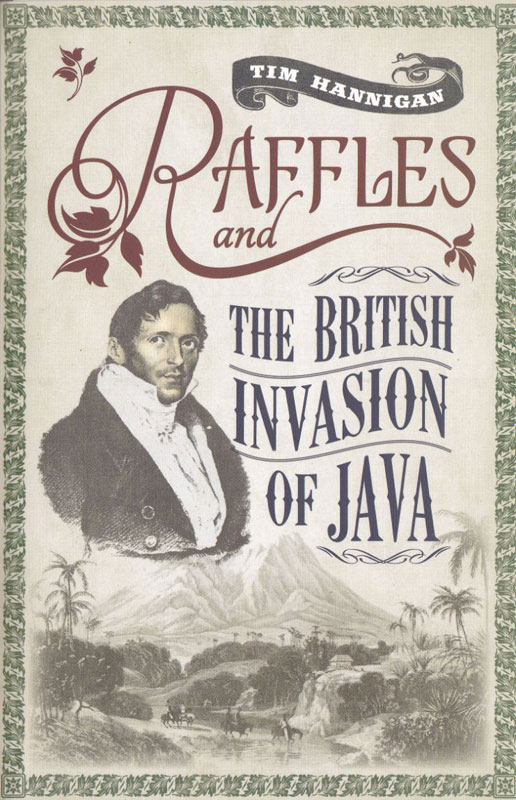

Raffles and the British Invasion of Java

Raffles and the British Invasion of Java

Tim Hannigan

Monsoon Books 2012

368pp

ISBN 978-981-4358-85-9

As a lad growing up in post-World War II London, I was force-fed a history diet which told me that Britain was great because it once had an Empire. I was taught that as an island nation, we had fought off the likes of the Spanish Armada, Napoleon and Hitler, and that our sea power had enabled us to civilise far off nations: we exported Bibles and imported resources such as cotton. Through our strict Protestant work ethic, our coal and our sheer inventiveness, we had harnessed steam and thus created the Industrial Revolution which was to prove a boon to Mankind.

All very simplistic and to our adolescent minds rather romantic. Our heroes were the adventurers and explorers such as Walter Raleigh who brought us tobacco, potatoes and gold he’d pirated off Spanish buccaneers. In 2002 he was listed in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

But Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles wasn’t. Until reading Tim Hannigan’s new published biography, I’d continued to share the notion that Raffles was a great man; discovering Borobodur, founding Singapore, and having a hotel named after him seemed to be credit enough. Mind you, I wasn’t sure that the rafflesia which also bears his name was intended as a compliment: the world’s largest flower emanates a stink akin to that of a rotting corpse.

Hannigan gives solidly researched grounds – see the closing bibliography – for suggesting that the flower might be the most appropriate recognition.

Hannigan’s is possibly just the second*1 of some 20 biographies which isn’t hagiographic, extolling the East India Company’s representative’s “saintly virtues”.

Unlike the majority of other biographers of Raffles, Hannigan has lived and worked in Java, speaks Indonesian and has written on the history and culture of this fascinating island for the mainstream English-language media here, and the Asian Geographic Magazine. His researches, both here and in the Reading Room of the British Library in London, were meticulous, and included a “source … which the Raffles-worshippers had always ignored: the other side of the story. An account existed of the years when Raffles ran Java, laid out in the allusive stanzas of high Javanese, written by a local aristocrat.”

This refers to the sacking of the royal city of Yogyakarta on 20th June 1811 in order to replace the Sultan with one more compliant to British rule. When it was over, “just 23 members of the British party had been killed, and a modest 76 had been wounded. All along the battlements meanwhile, tumbled in the ditches, abandoned in the alleyways and heaped in great steaming piles in the broken gateways, were thousands of dead Javanese.”

How Raffles came to be Lieutenant-Governor of Java is a tale of patronage and egotistical connivance and ambition.

The suggestion that Raffles came from a poor family is patently false. His father was the captain of the slave ship on which he was born. That he left school at 14 was not unusual (as did this reviewer’s grandfather a century later); however schooling was a privilege for a minority in the early 19th century. Through the ‘patronage’ of his mother’s brother, he became a clerk with the East India Company, the de facto ruler of India, on a generous salary of £70 per annum. (Charles Dickens, who was born a year after Raffles set sail for Batavia, from the age of twelve worked a ten-hour day in a factory earning just over £15 per year.*2)

During his ten years as a Company clerk, and thereon, Raffles was a prodigious autodidact, with a curiosity and drive which attracted both admiration and resentment.

In April 1805, Raffles and his recently wed wife Olivia set sail on a five month voyage to Penang where he was to be the assistant secretary to the newly appointed Governor of Penang. Why he was granted the position at a salary of £1,500 – an incredible rise from his then probable annual salary of £100 – has never been satisfactorily explained. Gossipmongers of the time said that it was related to Olivia’s ‘dark past’, a relationship with the Company Secretary, William Ramsey, but she never faltered in her support of her husband.

Once in Penang, Raffles impressed Lord Minto, the Governor-General of India, sufficiently to be given the task of gathering information about Java, a project which the Company had been discussing for a dozen years. Raffles later claimed that it was he who had initiated the Company’s (mis)adventures here because it “was worthy of His Lordship’s consideration, beyond the Moluccas”.

Hannigan brings to the fore other dramatis personae of the British inter-regnum, few of whom have been treated kindly by history. Some, such as Major-General Rollo Gillespie, the military commander, was eulogised in his lifetime, but there is little trace of Col. Colin Mackenzie who surveyed Prambanan or John Leyden, an orientalist who beguiled Raffles with his scholarship and poetry. Others, Hannigan treats less sympathetically.

However, one thing is clear. All were subservient to Raffles’ self-aggrandisement, subsequently enhanced and polished by Sophia, his second wife. For more than a century, Singaporeans and we Brits have been under their spell. Hannigan has done us a great service with his – erm- spellbinding biography. It is packed with a wealth of background about the earlier history of Java, life in the sultanates with their intrigues, of the Mataram and Majapahit kingdoms, about how religions arrived with ill-educated traders, and the still relevant Javanese mysticism, with footnotes where appropriate.

I cannot praise Hannigan’s work highly enough, but have one caveat: a book with such riches for anyone with a smidgeon of interest in Raffles and Indonesia would greatly benefit from an index.

Source:

*1 Sir Stamford Raffles – A Manufactured Hero? by Nadia Wright.

(http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/mai/files/2012/07/nadiawright.pdf)

She suggests that the first was H. F. Pearson’s This Other India: A Biography of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (pub. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press 1957)

2 Ibid.