With Christmas and New Year almost here, plenty of people will be taking the opportunity to engage in some festive drinking.

If you’re holidaying anywhere in the archipelago, please take care to avoid any alcoholic beverages that may be tainted with lethal methanol.

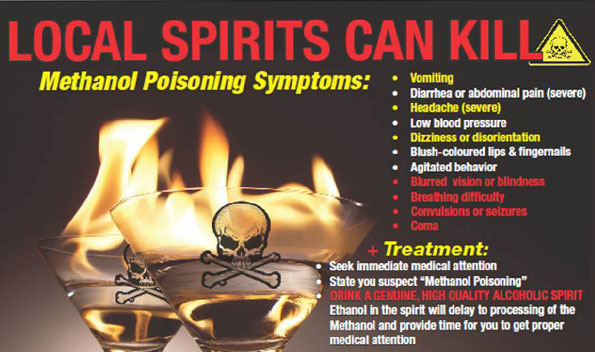

It doesn’t matter how experienced or heavy a drinker you are, as little as 30ml of methanol can kill. The Indonesian government doesn’t keep statistics on annual methanol fatalities, but based on media reports and anecdotal evidence, the death toll is estimated to be in the hundreds. Part of the problem is that many Indonesian doctors do not recognise the symptoms of methanol poisoning, let alone know how to treat it.

Fortunately, an effort is now underway to train doctors, provide medical equipment and raise public awareness, so that lives can be saved.

Tim and Lhani Davies, originally from New Zealand and now residents of Perth in Western Australia, lost their teenage son Liam earlier this year after he purchased a methanol-tainted drink from a bar on Lombok’s Gili Trawangan Island. They have channelled their grief into setting up a charity called Lifesaving Initiatives Against Methanol, which is undertaking a range of programs for toxicology education and training, and also aims to reduce the production of illegal and counterfeit spirits.

Liam was 19 years old when he and a group of friends were holidaying in Lombok. They were well aware of the dangers of methanol-tainted drinks in Indonesia and therefore had brought over their own bottles of duty-free spirits. Those bottles were quickly stolen from their hotel, apparently an inside job. When the youths visited Rudy’s Pub on Gili Trawangan, Liam asked the bartender if the top-shelf bottle of Smirnoff vodka was a genuine import. Assured that it was, he ordered a vodka and lime. Most of his friends drank beer. Liam later fell ill and was taken to a Lombok hospital, where he was misdiagnosed with a brain aneurism. He was later flown to Perth, where his condition was accurately diagnosed but by then it was too late for doctors to save him.

“There were a couple of points at which he could have been saved if doctors at the Lombok hospital had asked the right questions and made the right diagnosis,” says Tim.

Subsequent clinical tests on samples of alcohol from Rudy’s Pub indicated an unnaturally high methanol content in the drinks. Methanol is used in antifreeze, solvent or fuel. It is a natural by-product of local arak, which is distilled from the sap of palm flowers. Traditional distillers remove a small amount of toxic methanol, which is lighter than safe ethyl alcohol. But this lightness doesn’t mean that methanol rises to the top of a bottle of counterfeit spirits. That’s because methanol is soluble in water (or dodgy cocktails). So how is it possible that four or more people can share a bottle of methanol-tainted spirits, yet only one of them dies? That’s because the body’s methanol tolerance and assimilation rate varies among individuals, depending on their genes and how much regular alcohol may be in their system.

It is suspected that some unscrupulous bar managers add local methanol-tainted spirits to international brand-name bottles to stretch their profits. The government’s high taxes on imported spirits place them beyond the reach of most Indonesians, while most of the spirits sold in Indonesia have entered the black market. Certain distribution networks are tightly controlled by powerful individuals, often operating above the law.

Police identified at least one suspect in the case of Liam’s death, but prosecutors are yet to follow up with charges. When Tim and Lhani started their campaign for justice for Liam and to raise awareness, there were some negative reactions such as: “Why all the fuss over one dead bule?” Yet their campaign is more about enabling medical clinics and hospitals to be able to deal with methanol poisoning. “It’s not about one foreigner. This is about saving future lives,” says Tim.

He and Lhani have been meeting with methanol producers, spirits producers and Indonesian authorities in the hope of developing better law enforcement and regulations concerning the importation and distribution of spirits. They would also like to see random testing of bottles of spirits to determine whether methanol is present. Such tests can be done within five seconds by using a spectrometer – should the Health Ministry, the Trade Ministry or the police wish to invest in such equipment.

With support from the Australian Agency for International Development, Tim and Lhani have organised a series of toxicology workshops in Bali, resulting in hundreds of doctors and nurses being taught how to diagnose and treat methanol poisoning. Local doctors with the know-how are to be sent to remote health clinics to continue the training.

With support from the Australian Agency for International Development, Tim and Lhani have organised a series of toxicology workshops in Bali, resulting in hundreds of doctors and nurses being taught how to diagnose and treat methanol poisoning. Local doctors with the know-how are to be sent to remote health clinics to continue the training.

Establishing the workshops at Denpasar’s Sanglah Hospital was not too difficult, as it has engaged in strong cooperation with Australian hospitals following the 2002 Bali bombings. Australian nurse Di Brown, who heads a sister hospital program between Sanglah and Royal Darwin hospitals, hopes to have teams of nurses assigned to remote areas to educate people about the dangers of methanol.

Many Indonesian doctors view all forms of alcohol poisoning as the same and attempt to treat it by getting the patient to drink water. Methanol poisoning can actually be treated by giving the victim pure ethanol alcohol, which stops the methanol from metabolising into formaldehyde and formic acid. A patient then undergoes haemodialysis to remove the methanol from the bloodstream. Many hospitals and clinics do not have such facilities. In Lombok, only one hospital has dialysis equipment and only a few individuals know how to operate it. Tim and Lhani are raising funds to help provide further necessary equipment and relevant training.

The couple has also been busy in Australia, running a campaign that warns school leavers bound for Bali and Lombok holidays about the risk of toxic cocktails.

In Indonesia, they are raising awareness by focusing on the hospitality industry, local communities and licensed distributors of alcohol. They also have a plan for airlines and travel companies to provide tourists with information on methanol as they enter Indonesia.

Tim, who has been visiting Indonesia for over 20 years, admits there are many challenges but he has already seen some positive results from the medical workshops, such as ethanol becoming more accepted as a form of treatment. “If there’s one positive thing to come from this tragedy, it’s that doctors will be able to save other lives,” he says.

For further information, including how you can help to raise awareness, visit the Facebook page of Life Saving Initiatives Against Methanol.