The Indonesian government claims that its high taxes on alcoholic beverages discourage heavy drinking but the reality is that many people are turning to illicitly produced liquor, sometimes with deadly consequences.

Every year, dozens of people across the archipelago are killed by consuming drinks adulterated with toxic substances, especially methyl alcohol, which is normally used as an industrial solvent and antifreeze, and sometimes as a racing car fuel. In the first 15 weeks of this year, the Indonesian media has reported more than 50 deaths from tainted alcohol.

Drinking as little as 5ml of methanol can destroy the optic nerve, hence the term ‘blind drunk’, while 30ml can be lethal, although some people have survived ingestion of 100ml.

Methanol occurs naturally in humans, animals and plants, so the body can cope with miniscule quantities. The liver converts methanol into formaldehyde, which is then oxidised into formic acid and either eliminated in urine or broken down to carbon dioxide. But if an excessive amount is consumed, the resulting formaldehyde build-up will be toxic. It can take up to 30 hours after drinking methanol-tainted alcohol to experience the full symptoms of poisoning. If ethyl alcohol (beverage alcohol) is present in the mix, it slows the entrance of methanol into the metabolism. After the initial period of inebriation, symptoms include blurred and painful vision, headache, nausea, dizziness, muscular pain, respiratory difficulties and convulsions. Within a few more hours, the results can be coma, organ failure, blindness, brain damage or death.

These dangers are well known, but many of Indonesia’s relatively low number of alcohol drinkers and some impecunious expats cannot afford heavily taxed liquor. Instead, they opt for the traditional brews that various regions have been making for centuries, or they may unwittingly buy a toxically tainted cocktail or counterfeit spirit.

Local concoctions come under a variety of names, a few of which are interchangeable. The best known drinks are: cap tikus (literally ‘rat brand’, a distilled fermented sago wine – a North Sulawesi specialty) brem (fermented glutinous rice wine), tuak (usually palm wine, but also refers to a fermented rice and sugar drink), arak (distilled fermented red rice, or distilled palm sap), ciu (distilled fermented sugarcane molasses – a Javanese specialty), lapen (a contraction of ‘langsung pening’ or ‘instantly dizzy’, this brew from Yogyakarta is a palm-sugar wine, and also refers to high-strength alcohol mixed with water and syrup) and sopi (distilled Koli palm-sugar wine – a Maluku specialty).

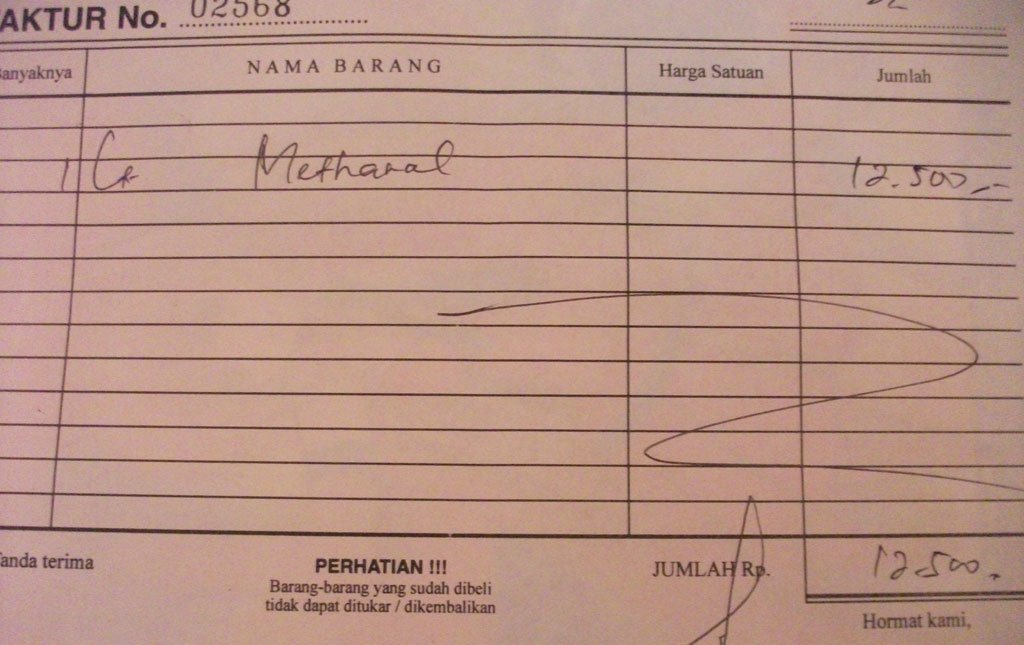

These cheap drinks are for sale at roadside stalls, mostly unregulated and unmonitored by the Health Ministry’s Drug and Food Control Agency. They are usually safe to drink in moderation, with alcoholic content ranging from 5% to 70%, and at worst will cause only a hangover. Problems start when unscrupulous distillers, resellers or imbeciles decide to increase alcoholic content by adding either ‘rubbing alcohol’ or methanol. Rubbing alcohol, which contains approximately 70% pure, concentrated ethanol, is primarily used as a disinfectant and surface cleaner, and can be bought cheaply at any pharmacy. Methanol can be bought from chemical suppliers for Rp.15,000 per litre. Bleach can be used to remove dye from methylated spirits. Some stallholders market their moonshine as jamu (traditional herbal remedies) in order to avoid upsetting religious groups or local authorities opposed to alcohol.

Health and trade authorities in Bali have regulated the traditional liquor industry in order to collect taxes, but there remains the risk of getting a drink from a tainted batch. In April, a Japanese man living in Jimbaran died after drinking methanol-laced arak. One of the worst cases occurred in June 2009, when 25 people, including foreign tourists, died after drinking toxic arak in Bali and Lombok. In September 2010, three Russian technicians working on Indonesia’s Sukhoi fighter jets in South Sulawesi died after drinking methanol-adulterated drinks. In June 2011, four Russian sailors died after consuming alcohol bought in South Kalimantan. Some countries have travel advisories warning of the potential dangers of Indonesia’s local spirits and suggest that tourists stick to bottled beer.

While the deaths of foreigners usually make the news, the vast majority of fatalities are young Indonesian men, often keen to prove their masculinity by downing dangerously strong drink at parties where hosts cannot afford expensive spirits. Victims tend to be from a low socio-economic background, generally pooling money to buy ingredients for a lethal cocktail to alleviate despondency. Yet alcoholism is not a huge problem in Indonesia, the chief exception being Papua province, where unfortunately there is a dearth of data on alcohol abuse. According to World Health Organization data, only 0.6% of Indonesian adults are high risk drinkers, which is defined as consumption of five or more standard drinks for males and three or more standard drinks for females on a typical drinking day. This data might not account for people drinking methylated spirits mixed with condensed milk. The government doesn’t provide statistics on alcohol consumption in rural communities, where some people engage in binge drinking at festivals and wedding parties.

Police and Customs officers occasionally raid producers and vendors of illicit spirits, especially ahead of Ramadhan, seizing thousands of bottles, which are sometimes steamrolled for the TV cameras. Some school students caught with alcohol earlier this year claimed to have bought it from police.

Aside from tainted local drinks, another problem is the counterfeiting of imported brands of spirits, as well as local brands such as Mansion House. Jakarta Police last year raided six illegal liquor factories that were producing thousands of bottles of spirits being sold as the real thing. The bogus brands included Chivas Regal, Johnnie Walker Gold Label, Martell VSOP, Hennessy VSOP, St-Rémy Authentic, Jim Beam, Jack Daniel’s, Pepe Lopez Tequila, Smirnoff No.21, Absolut Vodka, Bols Amsterdam 1575 and Gordon’s London Dry Gin. The operators mixed 90% strength industrial alcohol with bottled water and a variety of ingredients, including syrup, energy drinks, colouring agents and alcohol flavouring essences. The counterfeit liquor cost about Rp.40,000 per bottle to produce and was then sold to small cafes, bars and stores for Rp.70,000 to Rp.200,000 per bottle, whereas the genuine stuff would retail for about Rp.500,000 or more. Getting hold of the right empty bottles accounted for at least half of the production costs. These were bought from staff of nightclubs and restaurants for Rp.20,000 to Rp.30,000 each. The message for bar owners is simple: supervise the smashing of your empty spirits bottles lest they end up being refilled with counterfeit liquor. In China, many distributors and manufacturers of foreign liquor require the return of their bottles.

Some fakes can be spotted by printing errors on labels, plastic seals over bottle tops, blemished or chipped bottles, cloudy content, and most revealingly, by taste. One Central Jakarta cafe used to host a regular quiz night, with the winning team receiving a bottle of ‘imported’ spirits, but the usual victors complained it was definitely fake and made them ill. Police encourage the public to report any vendors selling extremely cheap spirits because it could contain lethal ingredients; however, it could simply be genuine stuff smuggled in with the complicity of crooked officials.

Workers in Jakarta’s counterfeit liquor factories are often part of syndicates but police seem to have trouble arresting ringleaders. Officers are more adept at nabbing small-time liquor vendors lacking a permit. In January a 72-year-old man living in a shack by the railway in Tanah Abang was arrested for selling vodka and wine. By comparison, when police in Palembang, South Sumatra, in April found a warehouse stocked with 3,000 bottles of illicitly produced liquor, the owner of the operation was let off with merely a warning.

There’s no easy solution to Indonesia’s problem of methanol poisoning. Alcohol taxes could be lowered and traditional liquor regulations tightened, but some people will likely continue to tempt fate with potentially lethal booze. Banning alcohol would only perpetuate the black market’s dominance and lead to more methanol use.

Kenneth Yeung enjoys an occasional drink.