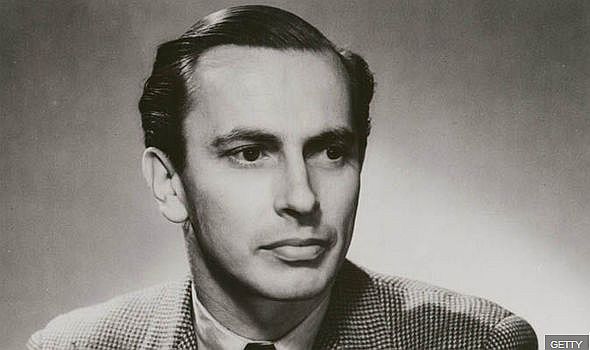

John Coast was 31 when he flew to Bukittinggi in 1948. His life’s journey until that point had been one of youthful idealism when he had flirted with fascism while a clerk with Rothchild’s Bank. Following the outbreak of the war against Hitler’s Germany, he enlisted in the Coldstream Guards who were sent to Singapore at the beginning of February 1942. Two weeks later he was captured by the Japanese invaders, and then spent the next three and a half years as a prisoner of war (PoW) working on the Japanese ‘death railway’ in Siam, as Thailand was then known.

After the railway was completed, alongside Dutch, Eurasian and Indonesian PoWs, Coast found himself in a camp with time on his hands. The “malaria-yellowed” minority were still fit enough to seek ‘entertainment’; Coast studied Dutch and Indonesian and came to appreciate Balinese dancing so much that he planned a post-war project.

“I wanted to take a really perfect Indonesian dancing company around the world to convince all those who saw them that the culture of Indonesia was a thing of excellence.”

The Dutch PoWs were certain that they would return to the Dutch East Indies to resume their paternalistic roles once they had been released. So they viewed Coast with suspicion, noting his developing anti-colonialist sympathies and his stated support for the nascent republican movement he was learning about from the Indonesians who had never had a country of their own.

The Indonesians claimed an international treaty, the Atlantic Charter, as the legal basis for their independence. This was a policy statement drafted by the leaders of the UK and the USA and issued on 14 August 1941, which defined the Allied goals for the post-war world. The key goals for Indonesians were: no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people, self-determination; restoration of self-government to those deprived of it; and disarmament of aggressor nations. The Atlantic Charter, with its signatories, led to the United Nations, which began with a conference in April 1945.

On 7 September 1944, Japanese Prime Minister Koiso had promised independence for Indonesia. On 15 August 1945, the Emperor Hirohito surrendered his forces and two days later, under pressure from radical and pemuda (youth) groups, Soekarno and Hatta proclaimed independence. Little of this would have been known to the POWs until their release in August and September 1946 when, according to Coast, the British POWs heard “with a mixture of amusement and sympathy, that the new Indonesian republican government was forbidding the return of our Dutch co-prisoners to the Indies where they said they had been so respected and popular.”

It was not until 27 December 1949 that the Dutch Queen Juliana signed the document transferring sovereignty to the United States of Indonesia. This followed the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference, which was held in The Hague from 23 August – 2 November 1949. John Coast was to find himself playing an integral part in the lead up to the conference, and that period forms the core of his memoir.

How he got there was a matter of happenstance. As can easily be imagined, the returning PoWs “were not in tune with the delightful, but rather grey, London of the winter of 1945. … So we ex-prisoners of the Far East found ourselves continually gathering together and talking about the years behind us.”

For Coast, that meant seeking out “the classical European ballet because of my prison-camp interest aroused by the classical dances of Indonesia.” Following a performance of the Sleeping Beauty, he determined to bring a Javanese dancing company to London “to show something of their exotic quality to this surprisingly dance-minded public.”

Needing to practice his Indonesian, in November he sought out some Indonesians. The key figure was Dr. Zairin Zain, who was to become Indonesia’s Ambassador to the United States in April 1961, when John Kennedy was in the White House. In 1945, he was an advisor to the Dutch delegation to the United Nations, then in London, and was able to give Coast an update on the situation. For example, as the Dutch had occupied Batavia, Soekarno and Hatta were transferring to Jogjakarta.

Zain also gave Coast an introduction to Dorothy Woodman, a “renowned figure in Left Wing politics“, Orientalist, and secretary of the Union of Democratic Control. Busy as she was with rallies against Franco, the fascist dictator of Spain, and “incessantly writing articles and pamphlets, she yet had time to be the supreme friend and contact-maker of all the young countries of South-East Asia.” These contacts included writers for the left-wing magazine New Statesman and members of parliament in the socialist government of Clement Attlee.

Zain first asked Coast to translate a pamphlet, Perjuangan Kita (Our Struggle), written by Sutan Sjahrir who was about to become Indonesia’s Prime Minister, for the meeting of UN delegates in London. And so began Coast’s journey towards his image “of this brilliantly coloured, brown-limbed, youthful and hot-bloodied land.”

His first step was to join the Foreign Office with the intention of becoming a press attaché in the Far East, and on 16 September 1946 he started “behind the desk of the Indonesian Information Service” with a hoped for posting of a few months in Jogjakarta, the seat of Indonesia’s first government. But first came a posting to Thailand, where he became “a typical bachelor around town” and very knowledgeable about the “sorority of birds of the night“.?And it is here in his narrative that a welter of information begins which may well boggle readers, yet is of historic importance.

Coast’s personal role as emissary and intermediary is the glue binding it together and one can glide through the pages, with the umpteen names tied in with enough “compromises, plots and counterplots, rumours and lies” to boggle all but academics.

That there are an additional 31 pages of appendices, a bibliography and index adds to the significance of this book, and much is owed to the editor Laura Noszlopy.?For this reviewer, a non-academic, what stands out are the descriptions of the places and people rather than the processes. His still relevant insights and ruminations resonate. Chapter 14, These Indonesians, closes with this: There can be no doubt at all that all colonizers treat their subjects consistently as inferiors, but the root of the trouble possibly is that those colonized do actually feel themselves to be inferior because they have been unable to stop themselves from being subdued.

Has there been a radical change of national mindset in the 64 years since those words were published? Many of us hoped that Jokowi’s pre-election mantra about changing the nation’s mindset meant freeing creative thinking, but we didn’t realise that ‘nationalism’ and ‘character building’ were what he wanted to perpetuate.

…………………………………………

Recruit to Revolution: Adventure and Politics during the Indonesian Struggle for Independence

Recruit to Revolution: Adventure and Politics during the Indonesian Struggle for Independence

John Coast (Edited by Laura Noszlopy)

Revised and updated edition published by NIAS Press 2015.?(First published by Christophers, London, 1952)?342pp.

ISBN: 978-87-7694-164-2

This book is only available for online purchase via Amazon where you’ll also find his account of his time as a PoW, Railroad of Death, a bestseller in 1946. There is a Periplus edition of Dancing Out of Bali, his account of his success in taking a troupe of Balinese dancers and musicians to Europe.