Writing a biography is very challenging. Not only does it include issues of access and information—length and depth—but it also risks exaggerating a subject’s importance. Such is not the case with Fitriyanti Dahlia, an author who wrote life stories of two important Minang figures, Roehana Koeddoes: Tokoh Pendidik dan Jurnalis Perempuan Pertama Sumatera (Roehana Koeddoes: Sumatran First Female Educator and Journalist, 2001) and Zakiah Daradjat: Embun Penyejuk Umat (Zakiah Daradjat: A Muslim’s Soothing Dew, 2013).

To Fitri, a similar background to and an honest struggle of the subjects are the keys to writing biographies.

“I wrote biographies of Roehana and Zakiah because I am a Minangnese. They had a very clear struggle and straight journey of life, not to mention that no data about them are complete. Above all, despite their Minang background, Roehana and Zakiah not only fought for Minang women, but went beyond their tribe, region and religion. While Roehana received a non-formal education from her father, Zakiah luckily enjoyed formal school and high education,” she said in a recent interview.

She further explained that her passion for writing biographies is inseparably linked to her discontent with her work as a journalist, requiring her to write what is assigned and her dissatisfaction with many biographies, which mostly deal with government or high-ranking officials rather than ordinary persons.

“Several biographies written are so much about state officials or great persons, not ordinary people with extraordinary work like Roehana. To this day, thoughts and struggles of Roehana remain relevant, not only in Indonesia but also in other parts of the poor and developing world,” she continued.

Fitriyanti’s work, Roehana Koeddoes: Tokoh Pendidik dan Jurnalis Perempuan Pertama Sumatera (Roehana Koeddoes: Sumatran First Female Educator and Journalist), published by Jurnal Perempuan in 2001, is regarded as the most complete book ever written regarding a biography of Roehana. Roehana could indeed be regarded as a figure who had a major role in education-oriented reforms during her time. Her important breakthrough was made as she established Kerajinan Amai Setia on February 11, 1911 in Koto Gadang. This association had more than 60 erudite women whose goals were to advance various aspects of women’s life in Koto Gadang.

She was a pioneer in the publication of a newspaper by and for women, called Soenting Melajoe. She even became its editor and wrote for it on a regular basis. Soenting Melajoe played a locomotive role in fighting against Minangkabau’s male domination, which in many ways deleted women’s rights. This role was highly visible from the various articles made by Roehana and other contributors in the post-1914 editions, suggesting many Minangkabau male authorities had emasculated women’s rights, whereas in fact Minangkabau had a special place for women. The paper helped the use of Malay among Minang women. This constituted Soenting’s great achievement, following a soaring trend of Minang-educated women to speak Dutch.

Having conducted extensive research on and written biographies of two Minang heroines—Roehana Koeddoes and Zakiah Dradjat—Fitri highlights a significant message.

“Female authors often talk about womanhood and women’s agony in their works. To be honest, this makes it hard for them to develop and leave that world behind. Roehana and Zakiah, on the contrary, are never trapped in exploring women’s anguish to the full. Roehana came up with a breakthrough by establishing a school (Kerajinan Amai Setia) and newspaper (Soenting Melajoe) for women, while Zakiah entered the ‘world of man’, and occupies the high position of Directorate General of High Education in Religious Affairs Ministry. Both Roehana and Zakiah demonstrate their core competence rather than complain about women’s afflictions.”

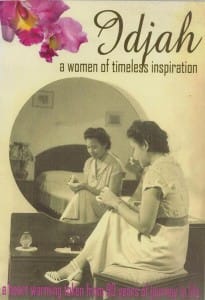

Born in Bukittingi on March 18, 1963, Fitri has been writing since young. When she was 12 years old, her pieces had been published in Pelita Daily. Along with biographies of Minang women, Fitri also has written and edited several other books; Perempuan Menyulam Bumi (Earth Embroidering Women, 2012); 100 Tahun Kerajinan Amai Setia (100 Years of Kerajinan Amai Setia, 2011); Meniti Hidayah-Nya: Mini Biografi Hj. Navitri (Passing His Guidance: Small Biography of Hj. Navitri, 2010); Idjah: A Women of Timeless Inspiration, 2010, Deadline: Kumpulan Cerpen (Deadline: Collection of Short Stories, 2008); Haji Amiruddin Siregar: Pimpinan Muhammadiyah Wilayah DKI dan Sekjen MUI (Haji Amiruddin Siregar: Muhammadiyah Chairman of Jakarta Chapter and MUI Secretary General, 2003).

At home, her daughter Annisa Maria Ulfah, 23, follows her path of intellectual tradition. When she reached the age of sixteen, Annisa published her first novel, Take Off or Landing, Awal atau Akhir (Take Off or Landing, Beginning or End).

“I’ve spoilt my daughter with lots of books since she was young. Without even asking, I always bought books for her every week. Annisa was familiar with tabloids, magazines, comics, novels in a quick manner. She was used to Kahlil Gibran since junior high school and possessed over 1,000 books,” she said.

“Reading comics, magazines, or novels should not be misunderstood for diverting children’s attention from school. Reading a lot serves to broaden their horizon of mind, so long as the books read are in proportion to their age, entertains and adds to their creativity. Never compare the kids’ current education system to their parents’ period. What must be done is that parents are required to adapt themselves to their kids’ system and trends,” she reminded.

In her attempts to encourage and disseminate a writing habit, Fitri, sometimes together with her daughter, travels across the archipelago to deliver what she calls ‘therapy for writing.’

“Writing is not to do with talent, interest and dreams, but it is a therapy of self-expression and introspection, expressing something beyond your reach. As you write what is going on around you, writing turns out to be a daily necessity. It looks like when you eat three times a day. There is nothing wrong with writing emotional articulation such as anger, abhorrence, sorrow, and others. Writing, to a serious extent, grows to be a therapy for the writer him/herself.”