“If the word of God had come down to the Indonesian archipelago, this is where it would have remained.”

– John H. McGlynn, Co-founder and Chairman of Lontar Foundation

For much of the world, Indonesia is an exotic country next to Bali, and Java is where coffee comes from. It’s viewed as a land of smiles, of gamelan, spices, volcanoes, komodo dragons, and photogenic rice terraces.

It’s also seen in the international media as a country of natural and manmade disasters; tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods, plane crashes, deforestation and occasional terrorism.

There are few foreigners who make the effort to dig deeper, to discover what makes Indonesia tick. One Jakarta expat who has, and has also done more than most of us to make Indonesia tick, is John McGlynn.

Although we have friends in common, we hadn’t previously met nor had I visited the Lontar Foundation’s centre in a backstreet of Pejompongan, Central Jakarta. From the outside, it is a modern looking house, but once inside I was impressed by the comfortable decor; dark wooden floors creaked, several alcoves were lined with full but tidy wooden book shelves, and there were enough comfy rattan chairs to provide the familiarity of a well-run library. I was impressed too by the large oil paintings which couldn’t readily be categorised as ‘Indonesian art’, but added to the ambiance.

The purpose of our meeting was to discuss Lontar which is noted for its translations into English of Indonesian ‘literature’, an often capitalised word which, as a non-academic, I viewed with some trepidation. I was taught to analyse ‘classic novels’ rather than to consider the stories and the background circumstances of the writing. However, John defines ‘literature’, in the broadest sense of the word, “as ranging from research reports, academic treatises, and patent schemes all the way up to film scripts, comic novels, and poetry.”

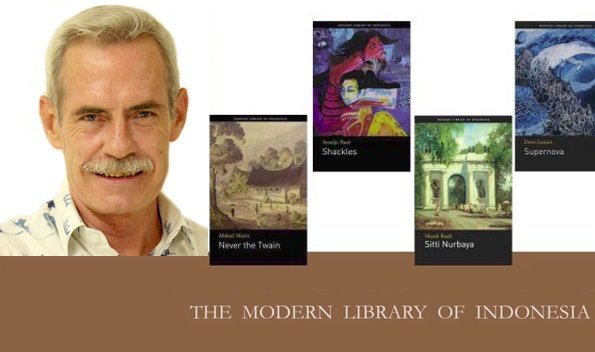

John first came here in 1976 to study Indonesian, which he did first in Malang and later in Jakarta, at the University of Indonesia. In 1978, he returned to the the USA to complete his university studies, gaining a Masters Degree in Indonesian Literature at the University of Michigan in 1981. Thereafter, he returned to Indonesia and it was while working as a freelance translator that he, along with Indonesian writers Sapardi Djoko Damono, Goenawan Mohamad, Subagio Sastrowardoyo and Umar Kayam, decided to found Lontar in 1987.

Lontar is primarily John’s ‘baby’. As Pak Goenawan has said, “John works single-mindedly for our purpose; to bring Indonesian literary expressions to the world.”

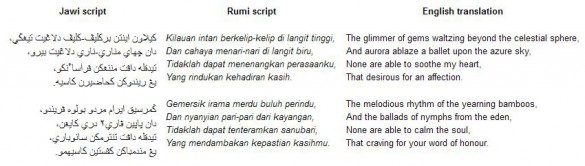

Even for a polyglot, that’s no easy matter. The lingua franca during the Dutch colonial era was Malay, the language developed throughout the region by traders over a thousand years. It was originally written in an Indic script and then, after the coming of Islam to the archipelago, in an Arabic-based script called Jawi.

Then in 1901 the Dutch linguist Charles van Ophuijsen introduced a more systematic spelling system, one that conformed with Dutch spelling practices. In 1947, after the revolution of Indonesian independence, this spelling system was replaced with Ejaan Yang Disempurnakan (Improved Spelling). The EYD system thus represents the third orthographic change.

Indonesian grew with Javanese, spoken by the majority, and other regional languages added to the complexity. It was not until 1972 that the EYD system was agreed with Malaysia, which had English and its own regional languages contributing to the mix, and hence Soeharto became Suharto, and Djakarta became Jakarta.

All this was largely irrelevant to most Indonesians, the large percentage of whom could not read or write. In rural Indonesia and urban kampungs the fantasy worlds of such Hindu classics as the Ramayana and Mahabharata stories were related by a visiting dalang (puppet master) who relayed their moral values, and during Soeharto’s Orde Baru often inserted his political messages.

In 1870, some of the Dutch-founded schools opened the doors for bumiputera (native Indonesians), albeit a privileged few. Moreover, it was not until 1950 that a six-year programme of compulsory elementary schooling was introduced to newly independent Indonesia.

Hence, when Soeharto assumed power in 1966 the literacy rate was c.50%. The adoption of ‘The Functional Literacy Program’, which ran from 1966 to 1979 and was followed by other programmes, raised the literacy rate for adults to c.83% and for children to c.90% in 1998, the year Suharto (was) stood down. However, their aim was for economic, productive reasons rather than for freedom of thought.

By contrast, writing, especially fiction, offers the context of ‘place’ and, in John’s words, “the better books have real people in them” and can therefore be subversive – much of Indonesian literature has the nationalist struggle as the historical background. Post-independence, with the bureaucracy and military at their disposal, Presidents Soekarno and Soeharto imprisoned and exiled writers. The dawn of reformasi in 1998 and the growth of the internet and other communications technology has seen many more Indonesians speaking out via text messages, blogs, social media and novels.

However, what John wrote in the essay Silenced Voices, Muted Expressions for an anthology of New Writing From Indonesia: Indonesian Literature Today published by the University of Hawaii in 2000, still holds true today. He wrote: “Having grown up under constraints of freedom of expression and inquiry, an entire generation has been traumatized into becoming a society of silence and avoidance. Not until today’s young people have unlearned the ways of repression and a new generation has been educated to respect and defend its right to freedom of expression will true openness and democracy come to Indonesia.”

There is also the need to foster a love of reading in early childhood which John believes should start at home. However, although I think that schools have a greater role to play, many parents and teachers still have the mindset inculcated during Soeharto’s regime, and only those who are enlightened, rather than blinkered with prejudices or self-interest, will encourage the freedom of thought engendered by easy access to fiction.

Good writing comes from wide reading, and access to it. So one of Lontar’s goals is “to stimulate the further development of Indonesian literature.”

In addition to its library of printed materials containing more than 3,000 books and other texts related to Indonesian literature, the foundation maintains a digital library which provides preservation and access to materials produced and gathered by the foundation over its 20+ year history including:

– Videos from the Indonesian Writers Series, Indonesian Performance Traditions, and Wayang Kulit/Shadow Puppet Theater Series

– Audio interviews and recordings with Indonesian authors and witnesses from significant events in Indonesian history.

– Archival photographs of traditional manuscripts, colonial-era postcards, and historical images from the New Order to the present.

Frankfurt Book Fair 2015

John says that the aim of Lontar is to “promote knowledge of Indonesia through its literature”, and it is natural that he is a member of the ‘Indonesian National Committee for Preparing Indonesia as Guest of Honour in Frankfurt – 2015’.

The first Frankfurt Book Fair was held soon after Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable type printing press in around 1439. Revived in 1949, it is now the world’s largest and most prestigious book fair. Since 1986 a country, or region, has been chosen as ‘Guest of Honour’.

However, with several government ministries and a large number of departments involved, as well as the Goethe Institut, Lontar and others, he thinks preparations should have been started earlier than the end of last year, if only to have a larger range of books at Frankfurt.

Over the years, John has worked with more than 100 translators and is well aware of the time required to produce a literary translation that “is both felicitous to the original text and appealing to the target audience”. However, a worrisome fact is that of those 100 translators “no more than a dozen are both truly fluent both in Indonesian and English.”

John further notes that “for the rest, a heavy dose of editing is usually required.”

However, some good news has recently been received; the Ministry of Education and Culture has established a translation funding program, the ‘I-Lit (Indonesian Literature in Translation) Program’.

For those who like to carry many books on their travels, the Kindle is ideal, John says, but we both agreed that with such devices something is lost. Printed books are shared, and one can learn a lot about folk by browsing their shelves of well-thumbed books.

Lontar books are available in Indonesia at Periplus bookstores and abroad through Amazon as print-on-demand paperbacks. They are also available as e-books through Book Cyclone.

Website: http://lontar.org/