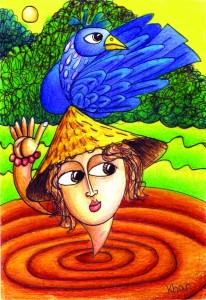

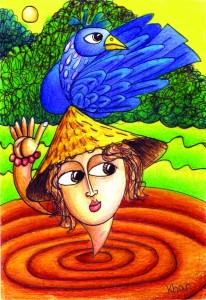

An excerpt from Looking for Borneo, images, words and music inspired by the book, Crazy Little Heaven.

Not far from here, at the end of an impossibly potholed jungle track, traditional Bahau Dayak ways are preserved in this rapidly developing region. The isolated village of Eheng sports a fine sprawling lamin or longhouse where families live the old way and continue to enact the rituals which ensure respect is paid to ancestors, and ancient spirits are appeased. On a previous occasion when visiting Eheng with my family, I was greeted with the evocative sounds of a village gamelan orchestra mingling with the beat of mallet and chisel as a Whuge tree trunk was transformed into a heavily carved, symbolic totem pole. I watched for a while. Human figures with grotesquely exaggerated genitals and facial features emerged from the raw timber entwined with snakes, dragons and classic swirling motifs.

I climbed a notched wooden pole to enter the raised longhouse. As my eyes adjusted to the dim interior, I took in a remarkable scene. A small group was huddled around playing the gamelan gongs in the slatted light inside. In one corner of the communal space which ran the length of the structure, a group of old men sat around a Dayak shaman chanting in an unintelligible local language. A large area was separated with hanging dry leaf strips and floored with rattan mats. Beyond this, women squatted beside a pair of large Chinese porcelain jars, busy in the preparation of a range of festive foods. Villagers wandered about, smoking and chatting with a sidelong glance or sometimes an open stare at our intrusion. In the centre of the cordoned area hung a large and brightly painted wooden box, decorated with a profusion of colourful rags and plaited reeds. Looking up to where this arrangement was attached to the ceiling high above, I could see a cluster of cheap china plates and bowls suspended upside down amongst the dust and cobwebs.

“What is all that for?” asked my son, Oliver, then eleven years old and trying to make sense of it all.

By this stage, the economic opportunities that our visit presented were being asserted and a range of carved and woven artefacts was spread out for our inspection. My attention was diverted from speculation on the meaning of it all, and I set about the more pressing business of souvenir shopping.“Beats me,” I replied, my Indonesian language not then good enough for me to find out.

It was not until some time later that the significance of this scene became clear.

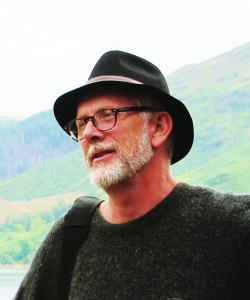

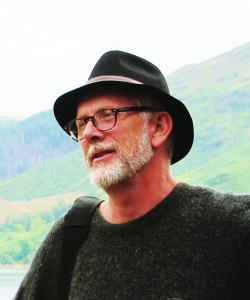

On a second visit to Eheng, a few months later, Tim and I met Michael Cope, an Australian anthropologist who for two years had been living on and off in the village and studying the Bahau people’s religion and changing society. Michael looked rather like a tall and bearded version of the scrawny kampung chickens that scrabble about beneath the longhouse, this appearance perhaps being the effect of a prolonged diet of nasi putih and local cigarettes. He was happy to have the opportunity for conversation in his native tongue with visitors interested in his research.

“Eheng,” he explained, “is a typically young lowland Dayak village. It was established around thirty years ago when the villagers migrated from the inland. Since that time only three traditional funeral ceremonies have been held. It just costs too much.”

The elaborate three-week-long rituals are apparently a financial burden few families can bear. To cover the costs of the funeral we had stumbled into on the previous visit, it is likely that the host family would have sold one of the priceless antique ceramic jars that were once traded upstream by Chinese merchants for precious jungle products, and have now become collectors’ items coveted by antique traders from the coast.

The totem pole or sepunduq I observed being carved was to be erected in the clearing in front of the longhouse, where it would serve as a hitching post for a sacrificial beast at the climax of the ceremony. In earlier times a human sacrifice would have been offered. After the funeral, the carved pole was probably sold to help offset costs. The colourful box hanging inside the longhouse had contained the disinterred and ritually washed bones of those family members whose spirits were to be released for their journey on the ship of the dead to a Dayak heaven.

“On the final night of the three weeks of rituals,” Michael went on, “those bones were taken from the box and given a wild party before they were put in their sandung.” As he talked he led us to the village cemetery where the sandung were to be found. A row of five or six carved wooden sarcophagi rested a couple of metres above the weedy ground on carved poles.

Such is the nature of the traditional Dayak culture, where the spiritual and the temporal are never far apart. The presence of both a Catholic and a Protestant church in the village, alongside the longhouse, indicates a flexibility of religious thinking that could perhaps be usefully emulated in other parts of the country.“The relatives and friends of the deceased sang beautiful songs to the dead on that night. It’s really very moving. The songs are incredible, quite haunting. I was at the last funeral held here. They sing songs which celebrate their lives in a very personal way. If the dead man liked a smoke, he is given lighted cigarettes. They give them their favourite food and a share of the grog too. They even dance with the skulls. The party would have gone on all night. It’s quite amazing.”

_____

Mark Heyward has lived and worked in Indonesia for over twenty years. His 2013 book, Crazy Little Heaven, an Indonesian Journey has become a best seller in this country. This story is an excerpt from a new coffee table book titled Looking for Borneo, words images and music inspired by the book Crazy Little Heaven.

As Bill Dalton says in the foreword: “Looking for Borneo is a celebration of the island of Borneo, its environment and its people. At the same time it is a call to action, a plea to save this special place from the ravages of development. A collection of writings, drawings, photographs and music inspired by Kalimantan and Mark Heyward’s acclaimed book Crazy Little Heaven, an Indonesian Journey, this new volume is a unique artistic collaboration and a fine contribution to the body of Indonesian travel literature.”

Looking for Borneo will be released at a special event at the Ubud Readers and Writers Festival, at the Ubud Botanical Gardens on the evening of Friday October 3rd. The event will feature an exhibition of Khan’s artwork and David’s photography, live music from Mark’s album by Qisie and friends, readings accompanied by music and images -— and traditional Dayak music and dance. All are welcome.