Belgian reporter Tintin is one of the world’s most enduring comic book characters, especially in Indonesia,

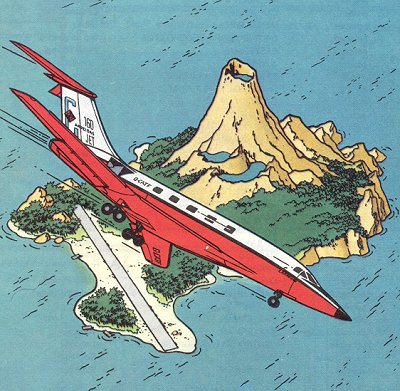

which was the setting for his 22nd adventure, Flight 714, a tale of hijacking, alien abduction and separatist rebels on a volcanic island.

Tintin first appeared in 1929, the creation of cartoonist George Remi, who used the pen-name Hergé (a reversal of his initials G.R.). He completed 23 Tintin books before his death in 1983. Adherents of political correctness condemn Tintin’s earliest adventures; the first, set in the Soviet Union, for its amusing anti-Communist propaganda and a couple of Chinese stereotypes, and the second, in the Congo, for its racism and big-game hunting. Both books were merely the work of a naive youth following the imperialist line of the Belgian Catholic church. In subsequent adventures, as Hergé matured, Tintin became respectful of other cultures and wildlife, notwithstanding the odd Jewish stereotype (rooted more in humour than anti-Semitism) and a scathingly accurate portrayal of the Japanese invaders of China.

Hergé never visited Indonesia but his meticulous research ensured his depictions of the country were fairly accurate when Flight 714 was published in 1968. The title refers to a Qantas flight from London to Sydney with a stopover in Jakarta. There, Tintin and his companions board a millionaire’s private jet, which is hijacked and lands on the fictitious island of Bompa in the Celebes Sea. The island has an unlikely mix of fauna, notably a komodo dragon and a proboscis monkey. The former is found only on six islands in East Nusa Tenggara and the latter is indigenous to Kalimantan. Fans obsessed with finding realism in fiction explain that sailors must have picked up the monkey and dragon separately and let them escape on Bompa.

More realistic are the illustrations of Kemayoran Airport, which was Indonesia’s first international airport and operated from 1940 to 1984. The old air traffic control tower still stands in the northern part of Central Jakarta, along with some of the terminal and tarmac, while the rest has disappeared to make way for development. The tower is a protected heritage building but has fallen into neglect. The Tintin Indonesia Community is campaigning to have the tower renovated and preserved as an aviation museum.

Precisely when Tintin was first published in Indonesia is a mystery. A low quality, black and white edition of one adventure was reputedly printed in the 1960s but no one has been able to produce a copy. In 1975, now-defunct publishing firm Indira began printing Tintin and won legions of Indonesian fans. Indira’s text was translated from the English-language versions of the books, so readers grew up knowing the characters by their Anglicised names. Tintin’s whisky-loving dog Milou (named after Hergé’s first girlfriend) was Snowy, while Professor Tryphon Tournesol was Cuthbert Calculus.

In 1970s Indonesia, all comic albums had to be vetted by the police to ensure they did not promote communism or other ‘subversive’ values. Old editions of Tintin thus have a signed police stamp on the final page, declaring the book authorised for circulation. Notable censorship was inflicted on Tintin’s fifth adventure, The Blue Lotus, which takes place mostly in China. Because of the Suharto regime’s ban on Chinese characters, the book’s calligraphy, which included several jokes, was entirely excised. Scenes of opium smoking were untouched.

When publishing giant Gramedia in 2008 acquired the rights to Tintin, it made fresh translations from the original French editions, resulting in changes to the names of some books and characters. Snowy became Milo, while Calculus was renamed Lionel Lakmus after ‘litmus paper’. The moustachioed detectives Thomson and Thompson (who don’t appear in Flight 714) reverted to Dupont and Dupond. Some of the catchphrase curses of Tintin’s alcoholic friend, Captain Haddock, were changed.

The Gramedia editions are smaller but sturdier than the Indira albums. Some older fans feel the new translations are weaker and have lost part of the humour. Another change is the text, which used to be hand-lettered but is now a uniformly lifeless digital font, as is the case in all modern editions worldwide. The Indira editions have become collectables, especially those in hardcover.

Gramedia’s edition of Flight 714 contains a careless error in the lead-up to the book’s funniest scene. The chief villain is trying to get the kidnapped millionaire to reveal the number of his Swiss bank account containing “more than 10,000 dollars”. The correct figure should be “more than 10 million dollars”.

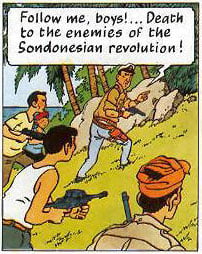

Most of the Indonesians in Flight 714 are ‘Sondonesian’ separatist rebels, hired as mercenaries. The chief villain promised to support their fight for independence, but considers them “poor deluded fools” and plans to kill them after they have done his dirty work. Much like how real separatists have been manipulated in Indonesia. Some commentators claim the rebels were based on East Timor’s pro-independence fighters. That’s impossible, given the Sondonesians speak Malay (not Tetum) and in 1968 it would be another seven years before Indonesia annexed East Timor. More likely the Sondonesians were modelled on Maluku separatists, whose independence struggle was not quashed until the 1960s.

There’s a fascinating level of detail in Flight 714’s illustrations, right down to wrecked planes and ships from World War II on the island. The main complaint about the book is that its ending is a literal deus ex machina – a pretentious way of saying an unlikely new plot device is suddenly introduced to resolve a problem.

The only other Tintin book set in Southeast Asia is Tintin in Thailand, an inevitably vulgar parody published in 1999. The Hergé Foundation sought to have it banned, not least because of the profanity and sex.

Tintin’s actual values of selfless egalitarianism and humanism are shared by the Tintin Indonesia Community, which moved quickly in response to this month’s Jakarta floods to provide assistance to victims.

Hergé’s last completed book, Tintin and the Picaros, could serve as a good analogy for the Indonesian political scene. Rival generals fight for power and a palace coup is staged but the masses remain poor no matter who is in power.

Kenneth Yeung is a lifelong Tintinophile.