“Turning around while the Creator said: That is how it descends to earth. The arrangement of the wind is very perfect in front of it. The Manurung Aji Paewang is probably good. It is brought down to earth.”

(“I La Galigo”, Buginese epic)

Travelling between Indonesian islands, it’s easy to get absorbed by the breathtaking features of the landscape, wildlife, and delicious food. It’s often forgotten that these lands are so much more than that. With every step we take, we could be walking on layers of history. Most places, no matter how ordinary or cosmopolitan they might look or feel, are a result of cultural and historical sedimentation of accumulated past human action that left traces, if you know where to look for them.

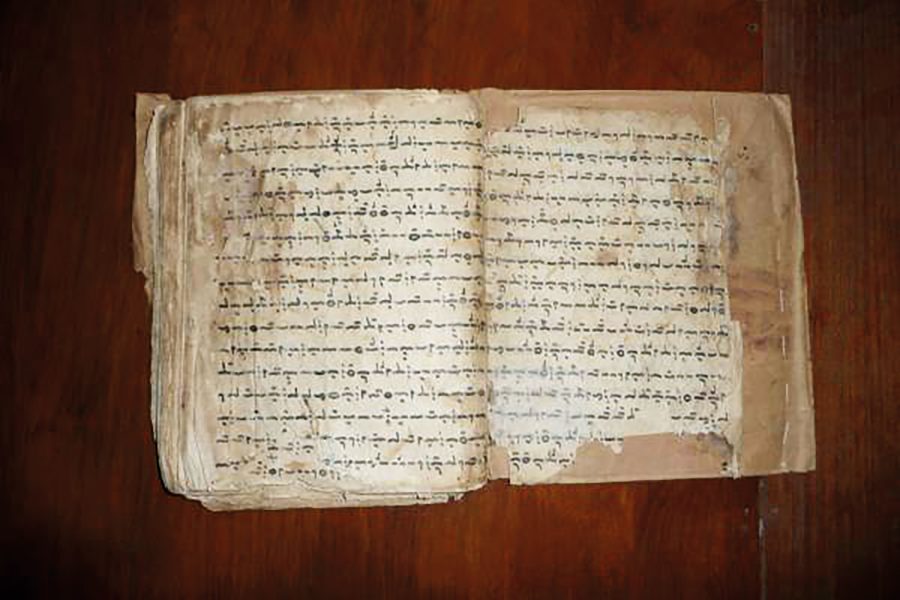

I wanted to start this article with a passage from the South Sulawesi Buginese oral epic story, I La Galigo, the longest literary work in the world, overshadowing works like Mahabharata or the Iliad. This epic, with origins lost in the mists of time, is a creation myth of the Bugis people written down in manuscripts, starting in the 18th century in the Ancient Buginese script, spoken currently by only 100 people or less.

‘I la Galigo’ Manuscript, Leiden University, Netherlands

Sulawesi is an island situated in the biogeographical region called Wallacea, at the boundary between Sundaland and Oceania; a land that’s home to early human prehistoric sites that have had revolutionary implications for the understanding of early human migrations.

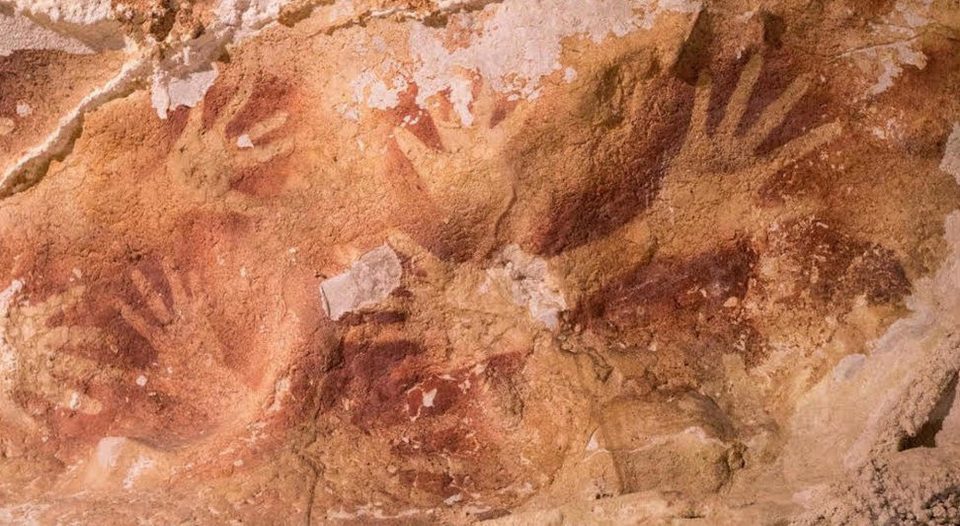

The most important prehistoric sites located in South Sulawesi consist of more than 20 karst caves, with mural paintings and hand stencils, including also previously unknown practices of self-ornamentation, use of ochre, pigmented artefacts, and portable art. These findings contributed to the search for the first human activities in the Late Pleistocene Wallacea, shattering our knowledge about the origins of art.

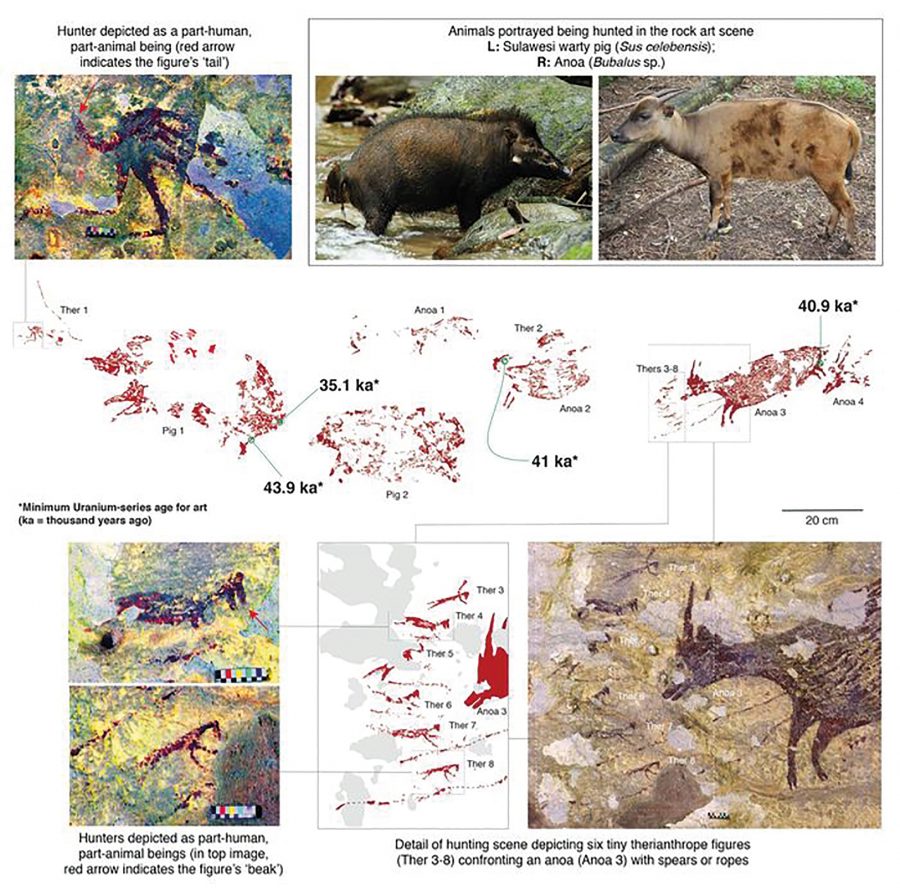

An hour’s drive north from the port of Makassar, the Maros-Pangkep cave complex has been known by the locals since time immemorial. Research started with the Dutch in the 1950s and was continued later in the 70s by British archaeologists, but it only made headlines in 2014 when M. Aubert and A. Brumm published their research. The two Australian archaeologists, currently based at Griffith University, used a new method to date the cave paintings based on traces of radioactive uranium present in the limestone cave formation’s ochre pigment. To their astonishment and disbelief, they found that the cave paintings date to 35,000–40,000 years old, making them as old, if not older, than the previously oldest known prehistoric cave art from Europe.

Maros-Pangkep Cave Complex (source: National Geographic)

Although I haven’t had the chance to explore Sulawesi and these caves, I became obsessed with their discovery, so I followed academic journals for articles written on the Maros-Pangkep cave complex.

European cave art, such as the Lascaux caves in France, is well known and has been long portrayed as images of the finest and most elaborate prehistoric art due to its conservation efforts. Mural painting inside caves is well known for the challenges it poses, its fragility making it urgent for measures to be implemented for its preservation. I found that the Sulawesi caves are in a quite bad condition, deteriorating faster than imagined although efforts have been carried out to manage the caves, mostly by the Conservation Centre for South Sulawesi Cultural Heritage (BPCB Sulsel). A few months ago, I decided to contact archaeologists in charge to get a more accurate picture of the caves’ condition.

Panels at cave Leang Bulu ‘Sipong 4 that date from the late Pleistocene (Source: National Geographic)

Adhi Agus Oktaviana, from the Arkenas Research Centre, wrote extensively on the Palaeolithic archaeology of Indonesia, including the Maros complex. He explained that every year, BPCB usually appoints one or several local people as caretakers of the caves on a yearly contract system and sets priorities for the protection of cultural sites according to their current fiscal year or in the year ahead. Further to our discussion, I contacted Rustan Lebe, a reviewer from BPCB Makassar who is conducting a study and monitoring the development of the damaged condition of several paintings of prehistoric caves in South Sulawesi and Southeast Sulawesi. It was revealed to me that from five cave samples, with a total of 340 individual paintings, 97 percent are damaged, and this is only based on a study back in 2015.

Needless to say, the Maros-Pangkep cave complex has been included on a tentative UNESCO list since 2009, though it’s still not accepted as a UNESCO protected heritage site. We can imagine that many problems hamper the UNESCO decision, and one of them would be the Indonesian government’s inability to provide a long-term sustainable plan for the area. As Dr.Budianto Hakim from the South Sulawesi Archaeology Centre explained, mining activities are a major factor in the damage of paintings for caves located in the cement industry areas, and the Sulawesi caves “will never be accepted as UNESCO Heritage sites, as long as the area is not sterile from cement activity or other types of mining.”

Painting of cave walls in the Pangkep area, South Sulawesi (photo: R. Cecep Eka Permana, 2005)

It’s only in the recent years that world heritage practitioners and local agencies have become aware that heritage places might also “belong” to ordinary people and to local communities who might have particular associations, feelings, attachments and so on to these places.

Very limited social studies have been conducted on the involvement of the surrounding community in South Sulawesi. This lack of understanding of the community situation makes it difficult for the government to determine long-term policies. Before we even begin to work on the preservation of the archaeological sites, the local communities’ struggle for recognition of their right to traditional land needs to be addressed. Denis Byrne, a Research Fellow in Heritage, describes that “the way that local places ‘become’ heritage places is not merely a normal aspect of community identity building; it is probably critical to the viability or survival of a community.”

Bugis, together with the Makassar and Toraja people of South Sulawesi, are indigenous Austronesian ethnic groups with a strong proud identity, and I sincerely hope that Indonesia will find a way to preserve their legacy and heritage for the future. Once we lose their culture, language and traditions we face the loss of an entire worldview.