Loggers, the big logging companies that is, are no longer contributing to deforestation in Indonesia. The reason: the Decree of the Minister of Commerce No. 25 of 2016, which stipulates that all timber must meet the standards of the Timber Legality Assurance System (TLAS), or in Indonesian Sistem Verifikasi Legalitas Kayu (SVLK). And the decree is being followed.

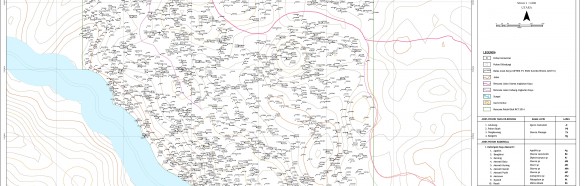

Before a tree can be cut and the log moved out of the concession area and onto the market, a number of stringent conditions have to be fulfilled. The most exacting of these is the logging plan. This plan needs to be submitted to the Ministry of the Environment and Forestry before logging can start. It contains a map (Peta Sebaran Pohon) of the blocks to be logged during a certain year, showing the location of the trees to be felled, coded with their lat-long coordinates.

Trees to be preserved are mapped the same way. Their identification is done in cooperation with the communities of forest dwellers and villages bordering the forest. These communities act as guides, indicating which areas are of special social or cultural value, for instance, burial grounds or dwelling places of ancestors. Trees with economic value, for example where resin is tapped, or honey collected from the hives of wild bees, also enter the to-be-preserved list.

The logging plan is in fact a geographic information system (GIS) and is the medium of control for sustainability. When a tree is felled it is recorded in the GIS and the log is marked with the appropriate code. Inputting this code into the GIS will reveal the date the tree was felled and its origin. Using the same code again is thus not possible.

The computer program makes use of high-resolution maps – scale 1:1,000 – that have been agreed upon by the stakeholders. This is of great importance, as inaccurate or disputed geo-spatial data would likely contain overlaps, thereby rendering the system null and void. Room for cheating is all but non-existent as both the suppliers and the consumers of logs are reluctant to use logs that lack certification.

It is said, however, that on a limited scale, illegal logging is still carried out, but only to supply small regional markets.

The success of this certification system is undoubtedly the main reason why on April 21 President Joko Widodo; the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker; and the President of the European Union, Donald Tusk; issued a joint statement that the EU and Indonesia have agreed to implement the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) licensing scheme to reduce illegal logging and promote the trade in legal timber. This licensing scheme was preceded by the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA), which was signed by the same parties in 2013 and ratified in 2014. A FLEGT license is issued after complying with the TLAS/SVLK conditions.

Although the European market takes less than 10 percent of Indonesia’s timber exports, TLAS, VPA and FLEGT have indeed contributed to the gradual implementation of sustainable forest management practices, and consequently to a reduction of illegal logging. Unfortunately, however, this is a first step only.

Much remains to be done on the long road to ending deforestation and the degradation of forest resources and land.

Large tracts of forests are still slashed and burned as an easy and cheap way to open land for oil palm and mining estates. Mitigating the effects of these activities will not be easy. It will require 1) a clear strategy agreed by all stakeholders; 2) effective monitoring; and 3) strict law enforcement by the government.

The outline of the strategy is known. But implementation is hampered by the complexities of the issues involved and the large number of stakeholders with widely differing and often irreconcilable ideas and objectives. How, for instance, can the needs of the forest dwelling communities for a sustainably managed natural forest be made compatible with an oil palm estate’s requirements of tens of thousands of hectares of clear-felled land? Legal and illegal land clearing for agricultural purposes is a major cause of deforestation. Both large estates and individual smallholders are the main perpetrators and the favoured crop is oil palm.

Apart from losing biodiversity and the habitat of protected species such as elephants, tigers and orangutans, the worst damage inflicted upon the environment by oil palm estates results from the slash-and-burn land-clearing method used to prepare the land for planting. Every year, hundreds of thousands of hectares go up in smoke and the negative effects are not only felt in the respective provinces, but also in Singapore and Malaysia. It would appear that incompetence or unwillingness of estate managers is to blame for this. Yields of oil palm estates and smallholders in Indonesia could be doubled from 30 to 60 tonnes per hectare if better agronomic practices were applied.

Increases in production could thus be achieved without burning and clearing more forestland.

Similar to the case of timber certification, the initiation of sustainable production methods is also bringing change to the oil palm sector, albeit slowly. The drive to strengthen sustainability of production was initiated from inside the industry. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was established in 2004 in Malaysia. The organisation evolved from the initial 47 members, largely from the industry itself, to 1,346 voting members, including 33 environmental and social activist groups and 612 manufacturers of consumer goods. RSPO is based in Zurich, Switzerland, and Indonesian producers and groups are among its members.

During the 12 years since its creation, RSPO has initiated certification of environmentally sound behaviour, which several major food and candy makers in the US and Europe now demand from their palm oil suppliers. More will certainly follow, as pressure is mounting on the buyers to monitor whether their suppliers adhere to internationally recognised standards and certification systems for sustainable production.

Mining companies too need large tracts of land. As most mining in Indonesia involves open-pit mining, the environmental consequences are typically horrendous, as first the overburden has to be removed, vegetation and all. And although the contract states that this has to be put back in place when the operations end, the reality is more difficult. Second, disposing of the mine tailings is a difficult and expensive process, and often causes environmental accidents resulting in toxic material spilling into the surroundings.

Whether the mining sector will eventually adhere to rules and regulations of environmental sustainability remains to be seen. The environmental management plans do outline and specify the various measures needed to safeguard the environment, but unfortunately examples of [accidental] environmental catastrophes, such as the discharge of toxic matter into the environment, are still far too common. Total avoidance of mining disasters would require the closure of the mines, which is not really a viable solution.