Where I come from people never die. Before you rush to buy a house next to mine, I don’t mean people live forever, I mean that English people will never say a person whose vital signs are at zero is ‘dead’. In polite company people who are close to the deceased will say they have ‘passed away’ or ‘gone to a better place’ or are ‘no longer with us’. In informal settings people will say euphemistically that they have ‘shuffled off this mortal coil’ or ‘popped their clogs’ or are ‘pushing up the daisies’. This is all to do with the traditional English ‘stiff upper lip’ and speaks volumes about our desperate need to avoid any type of sentimentality or emotion.

Some say this is not very healthy, that we should cry hard and release our grief. Some say we should wail and scream and beat our chests as they do. Some say we should prop the body up in a corner and get rat-arsed like the Irish do. But for the English, after a silent funeral, it’s off to the nearest relative’s house for a quick cup of tea and a cucumber sandwich then out of there ASAP. But apparently for some of us, funerals used to be very different.

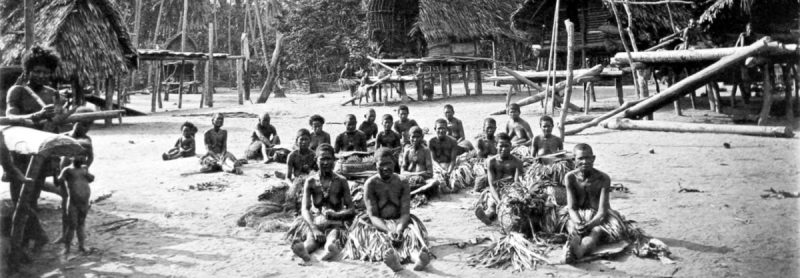

Up to and including the early part of the 20th century, the Fore tribe of Papua New Guinea (and some other peoples around the world) used to eat their stiffs (as far as our best anthropologists are aware) because they believed it was the best way to create a permanent link between the living and the dead. I guess the digestive system sorted the good bits from the bad bits and all the things they didn’t like about Aunty Doris got left steaming behind a bush and all the good bits became nutrition.

Unfortunately for them though, scoffing dead people from the same tribe, social group or society known as endocannibalism can cause a form of spongiform encephalopathy known as kuru (the bovine form is what we call ‘mad cow disease’).

In the early 1900s there was a major outbreak in Papua New Guinea after some members of the Fore tribe chowed down on a bloke from up the road who had developed the disease spontaneously, and the outbreak lasted until only a few years ago

The disease was unique to the Fore people and their closest neighbours and was caused by eating the chap’s infected organs – and worst of all it was orally transmissible. Because the men ate the choice cuts of meat and the women were left with the brain and other organs where the majority of the culpable prions resided, the disease mainly affected females and in some areas 25 percent of the women died as a result of it.

What is interesting is that, according to an investigation led by an Australian medical researcher called Michael Alpers, some of the people of the Fore tribe never contracted the disease even though they shared a ‘Chappy Meal’ with people who subsequently developed the disease and died horrible deaths. When he dug deeper, he found that these lucky people were immune because they had a particular gene profile that completely protected them. “Marvellous!” he thought. “From these people I can develop a vaccine that will stop this disease from spreading to the rest of the world!”

But Alpers got a shock. When he compared the gene profile of the uninfected Fore people to those of everyone else on the planet, he found that the immunity was far from unusual. Many people from other parts of Asia, from Europe and Africa, had developed the same immunity and had the same gene profile. His conclusion was that at some point in our history, maybe around half a million years ago, it was they who were eating our dearly departed and the Fore tribe who were not. We had developed immunity, the Fore tribe had not. For that reason the kuru disease stayed confined to the Fore people and never spread outside the area even though it was orally transmissible.

So, half a million years or so ago according to this theory, funerals in the area that we now call England may have been very different, especially the catering. Makes cucumber sandwiches seem even more boring!