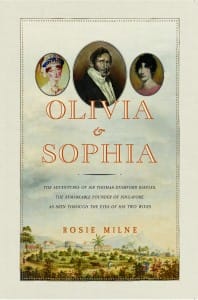

Author of Olivia & Sophie, Rosie Milne, explores what expat life was like 200 years ago.

My novel Olivia & Sophia explores the lives of two predecessors of modern trailing spouses. Olivia and Sophia both travelled from England eastward to Southeast Asia during the early 19th century, and when doing so must have been like travelling to the moon today. Each of them was a bold and admirable woman; they were respectively the first and second wives of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. He is remembered now as the founder of Singapore, but in his time he was the Governor of Java, and later, of Bencoolen, (Bengkulu) on Sumatra. Wherever Raffles went in the East, his current wife tagged along.

Writing about Olivia and Sophia made me grateful to be an expat wife now, and not 200 years ago.

For a start, there were the horrors of the voyage out, which could take anything from six to ten months. This was before sailing ships had stabilizers, and passengers were often prostrate with seasickness for much of the voyage. Imagine the lingering smell of vomit in damp clothes!

Except for the very rich, cabins were miserable, little dirty holes; dark, airless, and sometimes divided by nothing but slung canvas, making privacy impossible. In order to ensure supplies of fresh meat, milk, and eggs, animals and fowl had to be carried on the decks, adding to the general din and stink. And then there were the risks of shipwreck and pirates. Even the most nervous flier would surely admit that 15 hours cramped in economy from Heathrow to Soekarno-Hatta must be better than what earlier expats endured.

And what about travel within Asia? Bali-dwellers are probably accustomed to hopping to Lombok or the Gili Islands for the weekend. If you live in Jakarta, you probably think nothing of taking houseguests to Borobudur. But 200 years ago, Europeans were mostly confined in their colonies like rabbits in traps. Inland journeys were often by foot, through the clogging jungle.

Sophia, the first white woman to explore the interior of Sumatra, slogged up mountains and down waterfalls in full skirts – no hiking boots or breathable fabrics for her.

How would she have managed washing and going to the loo? What about rations? She found herself living off rice and claret. And there were no maps, so the adventurous were in constant danger of getting lost.

It’s not just ease of travel we take for granted today, but also ease of communication. Back then letters home took up to ten months to wend their way to England, and replies took up to another ten months to reach the East. Imagine a woman out here receiving the news her adult daughter had died, months after the event. That happened to Olivia – when she married Raffles she already had a daughter by an earlier relationship. Imagine a woman receiving a letter from her mother inquiring into the health of a child, after that child’s death. Four of Sophia’s five children died in Asia, and my novel imagines that she receives just such a letter. How lucky we are to have Skype, email, Facebook, and the rest.

And how fortunate we are that if we have five children, all five of them will in all probability survive to adulthood. Whereas back then fevers tore through infant bodies like tigers through chickens. How did women cope with the deaths of their children? For her part, Sophia relied on religion: a committed Christian, she regarded her children’s deaths as a lesson in faith from her merciful creator. Could you think like that? I couldn’t – though I had to pretend I could when I was imagining being Sophia.

It wasn’t only children who dropped like flies. Europeans out here 200 years ago simply didn’t know how to deal with the climate or tropical diseases. People fell ill in the morning and were dead by the evening. So many people connected to Olivia and Sophia died, that I found myself cutting many deaths, to prevent there being a funeral every page. But my poor subjects had to endure those frequent bereavements. How brave they were, and how lucky we are not to have to bury a friend, a child, or a spouse every other week.

Not to mention that modern Western medicines do not actively harm us, unlike the favoured treatment in Oliva and Sophia’s day: mercury.

This involved drinking salts of mercury, which made the breath stink, caused constipation, and made people drool like dogs.

Liver problems were particularly prevalent amongst Europeans out here, probably because of parasites, and because they all drank like fish, as the water was so bad. Olivia, who liked her cherry brandy, died of a liver complaint, after having suffered years of the mercury treatment.

And what of pregnancy? Ladies, imagine having to deal with the tropical heat, in your full skirts and woollen underwear whilst you were the size of a house. And, yes, women out here believed it was healthy to wear wool next to the skin! Furthermore, there was no air conditioning, no deodorant, and no running water – nothing to make living with the heat more tolerable.

And finally, there was giving birth. Sophia had no painkillers for her first four children’s births, although possibly she had ether for the last one. Her first child was born on a ship: imagine the difficulties of dealing with nappies! Her second child was born on land, but also arrived whilst she was travelling with her husband, with no nurse on hand, no friends on whom she could call for help, and only a botanist to assist. Not that she complained; women were expected to be stalwart, and she was.