“The memory of things gone is important to a jazz musician.” – Louis Armstrong

Joey Alexander’s nomination for two Grammy Awards has created a heightened international interest in Indonesia’s jazz scene, yet he is not the first child prodigy to emerge here playing jazz piano.

Jazz arrived in what was then the Dutch East Indies nearly a century ago, in 1919, and its entry represented a socio-cultural shift among the Dutch and Indo-European teenagers, much as the advent of rock ‘n’ roll did in the mid-‘50s in the USA. Because nothing happens in isolation, it is important to consider why.

According to the second complete census survey of 1930, the population of Batavia was 435,000 having grown from 306,000 in 1920, while the population of the Dutch East Indies was 60,727,233. Of these millions, just 240,417 were people with European legal status in the colony, and about 75 percent of those were ‘Eurasians’, the children of Dutch men who had taken ‘native’ wives for the duration of their contracts here.

There were also a number of foreign traders, including British, who were ‘in need’ of entertainment and amusement such as that experienced in Europe and the United States. This was provided by upmarket hotels that had their own house bands, theatres and a network of official Sociëteit Concordia, which offered theatrical and musical performances with dancing at weekends.

Jazz grew out of ragtime music (‘ragged’ rhythm), which originated in the red-light districts of African-American communities in St. Louis and was popularized by the publication of sheet music for piano performances by Ernest Hogan. Another African-American, Scott Joplin, registered Maple Leaf Rag in 1899; the earliest surviving recording of the tune is from 1906 by the United States Military Band.

Ragtime was popular in Batavia. For example, in May 1913 the Elite Cinema and Deca Park Theatre, which had live vaudeville acts, featured the American ragtime comedian and dancer Tom Richards.

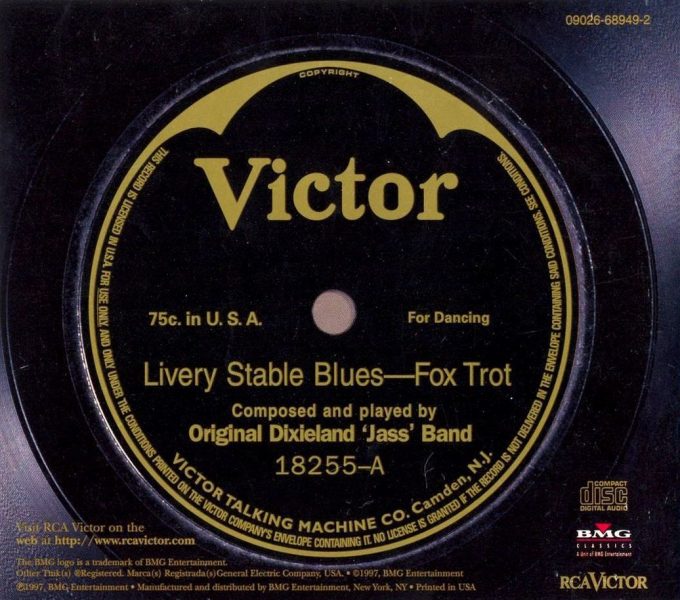

On 26 February 1917, the all-white Original Dixieland ‘Jass’ Band (ODJB) recorded two sides of a shellac 78rpm disk, Dixie Jass Band One Step/Livery Stable Blues, which are considered to be the first jazz recordings. Ragtime went out of style.

Just two years later, jazz (no longer ‘jass’) arrived in Batavia with the San Francisco-based Columbia Park Boys Club’s act – a group of 42 missionary boys. Their eclectic programme included singing, dancing, tumbling (gymnastics), with marches and jazz played on cornet, trombone, trumpet, and saxophone, with percussion. A reporter from the daily newspaper of the East Indies, Het Nieuws van den Dag dismissed the Boys Club show as a “sort of cocktail entertainment”. Although he found it amusing, the “loud and noisy music” gave him “stomach cramps”.

But the new music proved popular, particularly with older teenagers. As phonographs were already part of household furnishings, the heavy shellac discs were brought into the country from, it is suggested, Shanghai via Singapore. Live music surfaced too in upmarket hotels whose in-house staff bands, known as ‘string’ bands because banjos and violins predominated, soon began to include jazz in their repertoires for matinee and weekend dances.

It wasn’t long before high school and vocational college students decided to form their own dance bands playing the new music. However, it wasn’t in Batavia but in Makassar that the first band was started. In 1920, W.M. van Eldik formed the Black & White Band with his violin-playing 17-year-old brother-in-law Wage Rudolf Supratman, now better known as the composer of the country’s national anthem Indonesia Raya. They played at weddings and birthday parties.

The Batavia Jazz Band formed in 1922 with a line up of six banjoists, two C-melody saxophonists, a pianist, an acoustic bassist and drummer, all of whom had Dutch names. However, Pater who played the trombone and Geduld the cornet player were possibly from Suriname, the Dutch colony in the Caribbean. All were amateur, but their influences stretched to Ted Lewis and Paul Whiteman as interpreted from sheet music.

The following year the band folded and two of the banjo players, brothers Wim and Piet Bruyn van Rozenburg joined with four other students at King Willem III School to form The Royal Jazz Band, but on violin and alto sax respectively. They took their name from Koningsplein (King’s Square, now Monas) because they had a regular booking at the Railway Hotel on the east side, where Gambir Station is now.

Another band on the scene at the time was prosaically called The Original Jazz Band. It is now notable for its drummer: Moh. Aroef was the first recorded Indonesian jazz musician.

In 1926, a number of Filipino jazz musicians enlivened the scene, and 1928 saw the visit of a real American jazz band, that of drummer Jack Carter touring Southeast Asia after finishing a contract at the Plaza Hotel in Shanghai. Their live sound being so much better than recorded ‘platen’, they inspired the young local musicians.

A new band was formed at the end of that year with sax, trumpet and trombone, with Moh. Aroef on drums. They secured regular gigs in the restaurant of the Deca Park Theatre (north side of Koningsplein) on Saturday evenings after the film show, and at the Railway Hotel whose manager was Paatje Vos. At the end of 1926 he became manager of the newly opened Tjikini Swimming Pool at the Zoo (now Taman Ismail Mazurki), and the band, now called the Swimming Bath Orchestra, played the Sunday matinees, which started at 11am.

“The visitors first had a swim for half an hour and spent the rest of the matinee dancing to the lively music. At two o’clock they went home for their afternoon nap.”

Yes, it was a time of leisure for the very few.

Bands came and went as the personnel left school, were posted outside Batavia or returned to the Netherlands, so we jump to 1930 and the entry of Charlie Overbeek Bloem to the scene. Born in 1912, he was just six years old when he took his first step to fame by playing Paderewski’s Minuet in G at Schouwburg Weltevreden, now Gedung Kesenian.

Bloem was to prove a musical driving force not only in Batavia but also nationwide. At 18 he was leading a trio, the Jazz-O-Maniacs, which played in the King Willem III School hall. He was also a key player in The Silver Kings, named after a cigarette brand. They had gigs at elite hotels such as the Hotel des Indes, the Batavian Yacht Club and other society venues such as Sociëteit Concordia in Bandung, regularly broadcast live on the radio.

In 1936 the semi-professional band recorded two sides of a 78rpm disc for HMV, Dinah and Ma He’s Making Eyes At Me, which, sadly, doesn’t seem to have survived. In early 1938, Bloem resigned from the band and focussed as a solo pianist broadcasting live on Saturday nights on the government-approved radio network heard throughout the archipelago.

On December 7 1941, when Pearl Harbour was attacked, jazz in the Dutch East Indies came to an abrupt end as all able-bodied men were mobilized and despatched to their defensive positions to prepare for the Japanese invasion. The next chapter in A History of Jazz in Indonesia began in late August 1945 when Charlie Overbeek Bloem was released from the Japanese internment camp in Bandung.