A young investment banker sat opposite me at a recent meeting in a Jakarta high-rise building and coughed repeatedly without covering his mouth. I try not to be critical of the cultural quirks of Indonesia, but there’s nothing quirky about people coughing in your face.

I handed the banker a small pack of tissues from my bag, telling him that ebola and other diseases can be spread by coughing and sneezing. He cheerily assured me that he didn’t have ebola. Then a woman in the room, another banker, said she had read via Facebook that ebola was invented and patented by America so that vaccination companies could make huge profits.

Ebola is not an airborne disease – meaning it does not remain suspended in the air for long periods. It is generally transmitted by direct contact with a sufferer’s infected bodily fluids. Doctors say it can be spread by coughing and sneezing if infected droplets land on another person. It is not spread via mosquitoes.

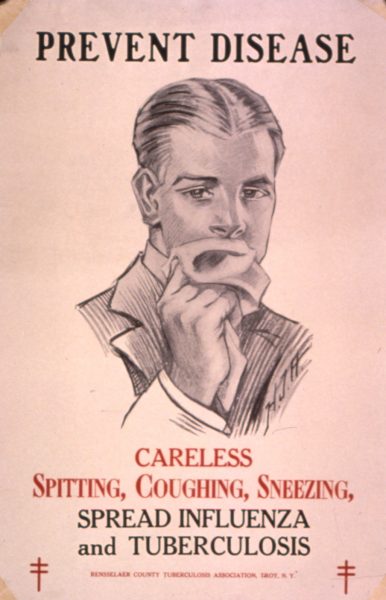

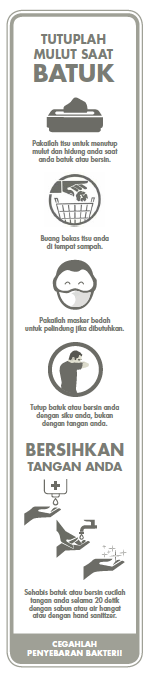

Indonesia has the impressive pass rate of 99.5% for its national high school exams. Despite such phenomenal cleverness, no one seems to be teaching people to cover their mouths when they sneeze or cough – preferably with a tissue or handkerchief, as many germs can also be transmitted by hand. Instead, there is an almost national obsession with masuk angin – the belief that being exposed to wind causes aches and pains, which can be remedied by having a coin scraped over the skin.

Anyone who watches local commercial television will be assaulted by noisy adverts for various “health” products, often involving an animated depiction of the medicine miraculously making the body stronger, the brain smarter or the skin whiter. Yet where are the public health awareness announcements? Well, there’s no revenue to be made by advising people how to minimize the spread of disease.

Ebola is the latest entry on the growing list of this century’s pandemic panics, which started with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in 2003, then bird flu in 2004, swine flu in 2009 and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012.

These health scares have not collectively claimed thousands of Indonesian casualties; hence there is some apathy toward ebola. The leading causes of death in Indonesia are: stroke, tuberculosis, cancer, traffic accidents, diarrheal diseases, heart disease and diabetes. So why all the international panic over viruses? Because a pandemic could wipe out millions. The 1918-19 influenza pandemic killed anywhere from 20 million to 40 million people worldwide, including about 3 million Indonesians.

These health scares have not collectively claimed thousands of Indonesian casualties; hence there is some apathy toward ebola. The leading causes of death in Indonesia are: stroke, tuberculosis, cancer, traffic accidents, diarrheal diseases, heart disease and diabetes. So why all the international panic over viruses? Because a pandemic could wipe out millions. The 1918-19 influenza pandemic killed anywhere from 20 million to 40 million people worldwide, including about 3 million Indonesians.

More recently, Indonesia topped the global human death toll for H5N1 bird flu. The World Health Organization recorded 638 human cases of bird flu over the past decade, resulting in 379 deaths, including 161 in Indonesia. H1N1 swine flu had a greater global impact, causing 19,633 human deaths over a 2009-10 pandemic, though Indonesia had few fatalities.

Ebola was identified in 1976 in Sudan and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). It was named after a river and was originally transmitted to humans from animals, possibly fruit bats, which are thought to be its natural hosts. The current outbreak in West Africa is causing consternation because ebola has a high risk of death, killing up to 90% of those infected. By comparison, the fatality rate for SARS is 10%, swine flu 21%, MERS 41% and bird flu 60%.

Some dedicated conspiracy theorists believe ebola is a myth or was invented to profit from vaccines and by stealing Africa’s oil and diamonds. The sort of cretins who think the 9/11 terror attacks on the US might have been an inside job because they read somewhere that no aircraft wreckage was found at the Pentagon – even though aircraft wreckage was found there.

Claims that ebola was patented in the US are true, but the motive was not to unleash misery upon Africa or to make money from a vaccine. The US government’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was in 2010 granted a patent for a strain of ebola known as Ebola Bundibugyo – whereas the strain currently spreading is Zaire Ebola. The CDC holds patents for various disease microbes so they cannot be patented by commercial companies that would then try to impose fees or lawsuits on researchers. The US Supreme Court last year ruled that naturally occurring genes are not patent eligible, which means researchers are less likely to be sued by big pharmaceutical firms. Vaccines for ebola are presently still in experimental stages.

The current ebola outbreak has been hitting Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, killing about 5,000 people. Further outbreaks have occurred in Nigeria and one case in Senegal. Indonesian doctors have warned there is a risk of the disease being transmitted through people travelling from Africa and the Middle East. Specifically, doctors said the virus could spread through the annual haj pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia.

The Religious Affairs Ministry in August declared it unnecessary for the government to issue a travel advisory about ebola to haj pilgrims. The ministry’s Director General of Haj Affairs, Abdul Djamil, said any warning could cause panic so should therefore be avoided. Nevertheless, many pilgrims were advised of the danger of contagion.

Saudi Arabia has banned entry to people coming from Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia in an effort to protect this year’s approximately 2 million haj pilgrims. Australia has also suspended entry visas for people from ebola-affected countries, resulting in accusations of racism and discrimination.

Indonesia’s new Health Minister Nila F. Moeloek last week said at least 72 Indonesians are working in the ebola outbreak area and should be monitored when they return, and quarantined if they have any symptoms.

The initial symptoms of ebola are fever fatigue, muscle aches, headache and sore throat. Next comes vomiting, diarrhoea, rash, impaired kidney and liver function, and sometimes internal and external bleeding. The early warning signs are also common for malaria, dengue fever and typhoid, so diagnosis of ebola has to be confirmed by lab tests.

Although ebola is not known to be in Indonesia, plenty of other diseases can be spread by coughing, including flu viruses, the common cold, strep throat, mumps, measles and tuberculosis. Common places for transmission of such diseases include shops, offices, public transport and schools.

Jakarta’s busway has stickers advising men not to grope female passengers. But there are no stickers advising people to cover their mouths when sneezing or coughing. An increasing number of Indonesians, mostly women, are wearing disposable facemasks in public to guard against disease transmission and/or inhalation of polluted air.

Last week in a fruit shop, I observed a woman sneezing vigorously, uncovered, as she examined some apples, which then glistened with her spray of saliva. President Joko Widodo’s call for a mental revolution has been hailed as a breath of fresh air. A good place to start would be teaching people to cover their mouths when coughing or sneezing, and to then wash their hands.