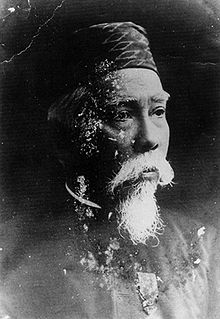

The first rather rambling title for this article ran nearly three lines as it tried to convey that Kassian Cephas (a) was the first Javanese professional photographer; (b) at the request of Sultan Hamengkubuwono VI (r. 1855–1877), was appointed as official photographer at the court of Jogjakarta; (c) photographed many monuments of Hindu Javanese civilization in Central Java.

Born in Jogjakarta, he became a pupil of Christina Petronella Philips-Steven, a Protestant Missionary in Jogjakarta. In 1860 he was baptized and took the name Cephas. Later, he began using Cephas as his family name. Cephas married Dina Rakijah, a Christian Javanese woman, at a church in Jogjakarta on 22 January 1866. The couple raised one daughter and three sons: Naomi (b. 1866), Sem (b. 1870), Fares (b. 1872), and Jozef (b. 1881). Sem, his eldest son, became a photographer and painter in his father’s studio. A biography of Cephas, entitled Cephas, Yogyakarta: Photography in the Service of the Sultan, by Gerrit Knaap, published by the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV), Leiden, 1999, presents a selection of 98 pictures: portraits of the royal family, court dances, town views, and of course the Borobudur.

Easy access to the court enabled Cephas to produce documentary work on its buildings, among others the Taman Sari Water Castle (now one of the main tourist attractions of Jogjakarta). He also recorded the various keraton (royal court) dances and other expressions of court culture. He was moreover able to engage in portrait photography of the members of the royal family and the sultan himself.

As official court photographer, he immortalized the court’s interactions with the colonial officers and visitors. An example of the latter is the recording of the visit of King Chulalongkorn of Thailand to Jogjakarta, in gratitude for which the King presented him with a case of three jewelled buttons.

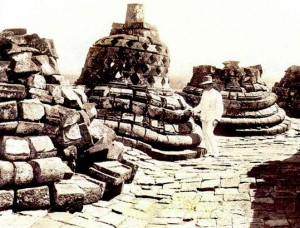

His most important work was, however, related to the many ancient buildings and monuments in Central Java. This includes, firstly, the Lara Jonggrang complex in Prambanan, which he photographed so precisely that these photos could later be used for the restoration of the temples. And secondly, the photographs of the hidden foot of Borobudur.

Borobudur was discovered in 1814 by H. C. Cornelius, a Dutch officer in the Engineering Corps. At the request of Lieutenant Governor General Thomas Stanford Raffles, Cornelis had been sent to investigate the existence of a big monument on a hill in the jungle near the village of Bumisegoro. It took Cornelius and his 200 men two months to cut down trees, burn down vegetation and dig away the earth and ash from Mount Merapi to reveal the monument. But due to the danger of collapse, Cornelis could not unearth all galleries. The report of his findings to Raffles included various drawings.

Hartmann, a Dutch administrator of the Kedu region, continued Cornelius’ work, and in 1835, the whole complex was finally unearthed. His interest in Borobudur seemed more personal than official. Hartmann did not submit any reports of his activities, in particular, the alleged story that he discovered the large statue of Buddha in the main stupa. In 1842, Hartmann carried out an official investigation of the main dome, but what he discovered is unknown and the main stupa remains empty.

The site served for some time, largely as a source of artefacts for “souvenir hunters” and income for thieves. In 1882, the chief inspector of cultural artefacts recommended that Borobudur be entirely disassembled and reliefs to be relocated into museums. This was based on his belief that the monument was largely unstable. The government ordered that a further thorough investigation be undertaken to assess the actual condition of the complex. The resulting report fortunately recommended that the site be left intact.

Borobudur did, however, remain a source of souvenirs; parts of its sculptures were looted, some even with colonial-government consent. In 1896, King Chulalongkorn, who visited Java and Jogjakarta, requested, and was allowed, to take home eight cartloads of sculptures taken from Borobudur. Several of these are now on display in the Java Art room of The National Museum in Bangkok.

Due to the lack of written records covering the construction of Borobudur, much of the monument is still enveloped in a cloud of uncertainty. And when, in 1885, a hidden structure under the base of the temple was accidentally discovered by Isaac Groneman, first chairman of the Archaeological Union, a new layer was added to this unknown.

The hidden foot was originally the first level of the temple; it contains 160 relief panels. Why this first level was closed and turned into a new foundation is not known. One theory states that during construction it was needed to prevent subsidence of the monument. Another is that the original base was incorrectly designed. Whatever the reason, the 160 panels (not all of them completed when the original first level was encased) were enclosed in a new foundation.

In 1891, at the request of Sultan Hamengkubuwono VII, the panels were photographed by his court photographer, Kassian Cephas. It should be emphasised that these photographs are the only ones in existence that depict the panels. The hidden foot was opened panel by panel, and after having been photographed, closed again. The budget for the exercise was prepared by the colonial administration, but for unknown reasons, Cephas received 3,000 guilders of the budgeted 9,000. Maybe it was felt that a native (photographer) operated at a different cost-level, or maybe the original plan to produce 300 photographs was considered excessive and unnecessary. In the end, 160 photographs of panels were produced, plus an additional four providing an overview of the site.

For a long time it was unknown what was depicted on the reliefs of the hidden foot. Only in 1929 was the French orientalist, Sylvain Levi (1863-1935), able to relate the panels to the Buddhist text of Mahakarmawibhangga, which had been discovered in Kathmandu, Nepal, in 1922. Apparently, the reliefs illustrate the theory of karma—the idea that an individual’s actions determine his fate, in the here and now, or in a future life! Quite a few could therefore be deciphered, but the meaning of others is still being discussed. The reading-sequence of the reliefs starts at the eastern stairs and skirts the temple clockwise. The panels are therefore to be read from right to left.

In the south-east corner, the hidden foot has been left open to offer a glimpse of what remains hidden.