Batavia, as Jakarta was called during the colonial days, was once styled the “Queen of the East”. This label was lost in the early years of the 19th century when it became known as the “Cemetery of the Europeans”. After the Dutch East India Company, VOC, went bankrupt because of mismanagement and corruption, and was formally liquidated in 1800, the town lost most of its raison d’être. It had been a town of traders and public administrators, with virtually no manufacturing establishments. With the demise of the VOC the inflow of respectable settlers all but dried up seriously affecting the population continuity. The sickly climate and abominable sanitation, had always taken a toll on large numbers of its inhabitants and with the replacements staying home the town slowly degraded.

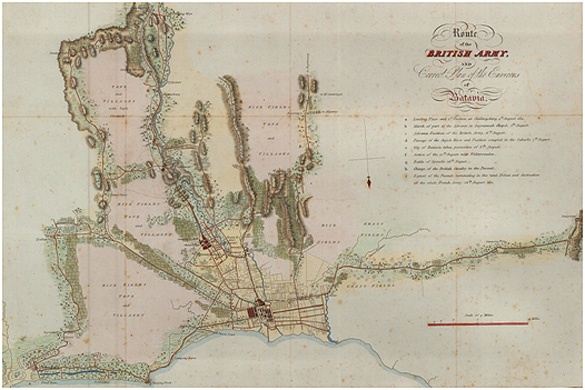

The general decline quickened because of the simultaneous depreciation of the Batavia Paper Currency. A devaluation of a currency, such as happened here, is typically followed by increasing poverty and widespread suffering. Merchants insisting on being paid in a more valuable legal tender—in this case the Spanish Dollar—and the civil servants and other employees still being paid in the old currency, strengthened the economic downturn. The situation improved only after the British took control of the archipelago in 1811.

The unhealthy conditions of Batavia had caused many of those who could afford it to move to higher grounds further south, that is, to Rijswijk/Weltevreden (Menteng), Meester Cornelis (Jati Negara) and Depok.

It was Governor General Daendels who in 1808 followed the privately induced moves by deciding to quit the dilapidated and unhealthy Old Town and build a new town center further south at Weltevreden. The Old Town (Kota) remained the centre of trade, warehousing and shipping, with Menteng housing the government offices, the military establishment and shopping. Interestingly, this situation remained virtually unchanged until fairly recently. Only the ever increasing home-to-office traveling time (residences of managers generally being in the south) and the availability of modern office facilities in the southern parts of the city, caused a relocation of the Kota-offices too.

Initially the reason to move further south was the very unhealthy conditions of the old Batavia. Located at the mouth of the Ciliwung and with many swamps and nearly stagnant ditches in its surroundings, the town not only suffered high rates of malaria, but also from pestilent air and poisonous water. The following excerpt is from Island of Java, by John Joseph Stockdale: … great degree of mortality which prevails there, especially among transient visitors, or recent arrivals; this is apparent to such a degree, that the English, who circumnavigated the globe, 1768-1770, and had experienced almost any vicissitude of climate, declared that Batavia was not only the most unhealthy place they had seen, but that this circumstance was a sufficient defence or preservative against any hostile attempts, as the troops of no nation would be able to withstand, nor would any people in their senses, without absolute necessity, venture to encounter, this pestilential atmosphere.

The health situation in Jakarta has greatly improved, although several foreign companies or legations still classify Jakarta as a hardship post and allow their staff biannual R&R leave of a few days in Singapore. The major problem of Jakarta nowadays is the traffic situation. Traffic jams are ubiquitous and unpredictable. Drivers seem to behave like a flock of starlings, without any visible or audible command, they suddenly all change direction: where for days the morning rush followed a certain road, this road could be all but devoid of traffic the next day as drivers had switched en masse to an alternative route.

Both the unhealthy conditions of the old Batavia and the endless gridlock of modern Jakarta are disconcerting and off-putting, to say the least, and highly frustrating as there is so little one can do about it. Staying away, yes! But once one has arrived there is no escape. And the frustration is augmented when one realises that traffic flow could be improved if only the system and procedures were regulated properly. Have you ever observed a knek (driver’s assistant who collects the fare, conductor sounds a bit too fancy) of a green-and-white Kopaja minibus, or orange Metro Mini, solve a gridlock by creating space inch by inch so that finally the plug can be removed and the traffic flows again… Don’t expect the same inventiveness and insight from the policeman, who would rather keep his stretch of road clean by sending you to the left when your desired direction is to the right or straight on.

The latest example of Jakarta’s fictional traffic regulations is the junction of Gatot Subroto and Rasuna Said/Mampang. In order to reduce the traffic on the intersection, drivers are now directed away from the crossing and are only heading towards their original destination after a final U-turn.

Highly frustrating, isn’t it! If staying away is not an option, my advice is: hire a good driver and sit in the back. Do some work, if you wish, or read and listen to music on your pod, pad or phone, or close your eyes and dream a bit. That last option is my favourite way to beat the traffic.

References:

The Conquest of Java, Major William Thorn, Reprinted in paperback by Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd, 2004

Island of Java, John Joseph Stockdale, Reprinted in paperback by Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd, 2003

Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch-Indië, Martinus Nijhoff, 1917

Wikipedias