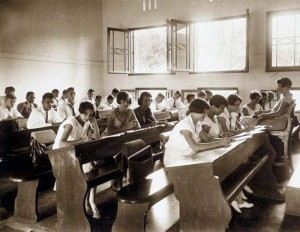

Indonesia’s historical baggage over the last century and a half means that as we tip headlong into this new fangled thing people call globalization, Indonesia’s educational infrastructure is struggling to catch up to the 1970s. Forget concepts like the Internet, creative thinking and meritocracy, many students are still being sat in lines to learn rote while the teacher, the epicentre of the learning experience, drones on and on, listing facts, dates and formulae to be remembered and regurgitated on demand.

While students in other countries are being taught to be comfortable in several different languages before first break, thinking here is dictated by old notions of master and servant. Witness the recent expulsion of five students from a school in Sulawesi for having the temerity to have some fun and post it online. The government strives for its noble intention of spending 20% of its budget on education, however it is worth bearing in mind the notion of learning for all remains in its infancy.

At the end of the 19th century, education was considered good enough only for the sons and daughters of the Dutch colonial masters and their Eurasian offspring. While there was a move for the indigenous elite to be educated to take over from the Dutch one day, the people out in the kampungs were studiously ignored.

In Surabaya for example, attempts were made at educating the populace with the opening of Mattschappij tot Nut van het Algmeen (which translates as Society for General Welfare), in 1853. This was a primary school with the aim of teaching Javanese kids a few basics but it closed down just seven years later.

Round about the same time a few places in the elite Dutch language schools were opened up to the offspring of the local elite, while in 1867 the government sought to develop local language schools at primary level though the students only received three years of learning before being thrown into the world.

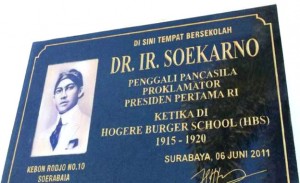

There seemed little desire to continue education. At the time there was a grand total of two secondary schools (Hoogere Burgerschool) on the islands, the Surabaya one opened in 1875 and by the turn of the century boasted a mere one local student. The teaching there was most definitely centred upon the system in the Netherlands.

There seemed little desire to continue education. At the time there was a grand total of two secondary schools (Hoogere Burgerschool) on the islands, the Surabaya one opened in 1875 and by the turn of the century boasted a mere one local student. The teaching there was most definitely centred upon the system in the Netherlands.

Despite the ‘expansion’ of the 1870s, by 1896 Surabaya boasted a grand total of 12 primary schools, eight of which were government run, with attendance extended to five years, while two were Catholic. For the vast majority of the population any learning came in the traditional pesantren where respected kyai taught students how to read the Koran.

As Europe was preparing for the First World War, the Dutch East Indies government was introducing segregated schools offering seven years of education with the final year in Dutch. The Hollandsch Inlandsche (HIS) and the Hollandsch Chineesche schools hoped to attract the wealthy Indonesian elite who tended to look down on local schools then, pretty much in the same way as they do today. For them, Dutch language proficiency was key.

In the years following the First World War, more and more children were going to school. In 1918 for example, just 407 students attended the two HIS; by 1929 there were 1,857 going to nine different schools. While the numbers of Europeans at school continued to rise and they remained by far the largest single percentage, the local population were beginning to take full advantage of the opportunities available to them. 19 new schools were added in Surabaya over that 11 year period with 15 of them aimed at the local communities.

The numbers looked spectacular, but they were coming off a low base. By 1930 it was estimated that only 14% of local children were in school, compared to 97% of the Dutch. There was still a lot of work to be done, but the financial crisis that gripped the world was felt in the Indies and the government reacted by cutting back on expenditure. In the case of education it meant concentration on Dutch schools and pulling back from the others, leaving a vacuum.

Into that space came organizations like Taman Siswa and Muhammadiyah. Taman Siswa was founded by Ki Hajar Dewantara in 1922 in Yogyakarta. A devout nationalist, he strongly believed in education as a way of empowering local youth while keeping them close to their Javanese roots and was influenced by Maria Montessori and Rabindranath Tragore.

As Howard Dick explains in his Surabaya, City of Work, “Just as Indonesian doctors had brought modern medicine to kampong families, nationalist organizations also brought modern education to kampong children… As youths many of these children would become prominent in 1945 in the fight for independence. The educated elite who led the movement for independence thereby helped sow the seeds of popular revolt”.

As Howard Dick explains in his Surabaya, City of Work, “Just as Indonesian doctors had brought modern medicine to kampong families, nationalist organizations also brought modern education to kampong children… As youths many of these children would become prominent in 1945 in the fight for independence. The educated elite who led the movement for independence thereby helped sow the seeds of popular revolt”.

Post war Indonesia was a mess as it came to terms with a Japanese conquest, a departing colonial master and the problems of establishing a new state. The colonial government’s retreat from education before the war meant a shortage of schools while investment in teacher trainers also suffered. In the heady days of Merdeka it was no longer ‘cool’ to study in Dutch while the best teachers, schooled as they were in the Dutch method, lacked the skills and empathy to teach in Indonesian.

Dick says, “The national government was too remote, too preoccupied with national and international politics and lacked cash to do what was needed.”

It wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 1970s that the central government, finally showing signs of stability after decades of chaos, was able to devote serious time and resources to education thanks to the influx of petrodollars. Schools started to be built again and the numbers of children attending primary school shot up while the government, unconsciously aping its colonial predecessor, seemed to adopt a hands-off policy to secondary school, allowing the private sector to take the lead with more than 70% of high school students opting for a private education.

Indonesia however, is still paying for that lost generation. Blighted by occupation and the birthing pangs of nationhood education has failed to keep pace with a growing population and a booming economy. A system that was painfully inadequate before World War II creaked and crumbled through 30 years of chaos and neglect. By the time investment did return and would start to have an impact, a whole generation went through an education that was painfully inadequate and that alumni, influenced by the events that surrounded their school days, are the ones now struggling to adapt to a time that is so vastly different to the one they grew up in.