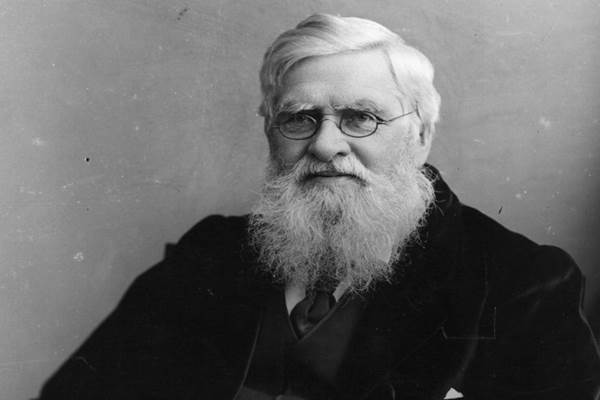

One hundred years ago, in November 1913, the famous explorer and naturalist, Alfred Wallace, died at the grand age of ninety.

Now his legacy is slowly returning to the public eye as he gains recognition for his overshadowed theories in the field of evolution. Aside from Tintin, of course, Wallace is my favourite explorer and for eight years between 1854 to 1862, he conducted research and collected specimens in the Malay Archipelago – the area now known as Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia. By coincidence, my favourite comedian Bill Bailey recently presented the fascinating documentary Bill Bailey’s Jungle Hero in two parts, about Wallace’s theories which were developed in Indonesia; Bailey makes some extraordinary and well-supported claims which are shaking up the establishment.

I was surprised to see Bill Bailey speaking Indonesian – calling himself orang lucu (funny guy) to the Sultan of Ternate as he presented a gift-box of French biscuits on this volcanic island where Wallace stayed. However, Bailey has a long relationship with Indonesia which he has explored for 15 years – he even married his wife on the island of Banda. As Bailey followed Wallace’s routes through Borneo, Sulawesi and the Spice Islands, he pulled out his copy of Wallace’s book The Malay Archipelago and explained some of the theories – including the Wallace line – a boundary between two very zoologically different regions in the Archipelago. However, as Bailey reached the Spice Islands, the documentary’s revelations began to intensify.

I was surprised to see Bill Bailey speaking Indonesian – calling himself orang lucu (funny guy) to the Sultan of Ternate as he presented a gift-box of French biscuits on this volcanic island where Wallace stayed. However, Bailey has a long relationship with Indonesia which he has explored for 15 years – he even married his wife on the island of Banda. As Bailey followed Wallace’s routes through Borneo, Sulawesi and the Spice Islands, he pulled out his copy of Wallace’s book The Malay Archipelago and explained some of the theories – including the Wallace line – a boundary between two very zoologically different regions in the Archipelago. However, as Bailey reached the Spice Islands, the documentary’s revelations began to intensify.

We all know that Charles Darwin developed the theory of evolution through natural selection, but what do we know of Wallace – the co-originator of this theory? In fact Wallace was the first to compile together the theory in written form, which he innocently sent in a letter to Charles Darwin; the letter was published in 1858 without Wallace’s knowledge alongside a paper by Darwin. In the introduction to this article of their joint breakthrough, Charles Lyell wrote: “These gentlemen having, independently and unknown to one another, conceived the same very ingenious theory to account for the…perpetuation of varieties.” Instead of sending it straight to a journal for publication, poor Wallace had unwittingly sent it to a rival. “He was robbed”, Bailey states.

Despite Wallace’s initial fame and having authored 22 books and over 200 scientific papers, over time his name has evaporated like steam. But thanks to Bailey’s efforts, a portrait of Wallace has been erected at the Natural History Museum beside a statue of Darwin and the ceremony was attended by Sir David Attenborough. There is also an ongoing project at the museum to upload all of Wallace’s letters on an online database so that researchers can discover more about this heroic naturalist.

Wallace’s dedication to research and his perseverance through rainforests in an era of head-hunters, poor medication and tropical diseases was quite admirable. Sometimes he thrived after obtaining enough specimens to support his research, but there were also times of dearth and deprivation. He was a humble man with financial difficulties – an outsider in the elite scientific circles of the time – perhaps this spurred him to become a socialist and in The Malay Archipelago, he criticised the “social barbarism” of Industrial Britain.

Fascinated by his story, I recently visited one of the villages on Gam Island in Raja Ampat, where Wallace stayed in 1860 where a Papuan friend of mine still lived with his family. The locals knew about Wallace’s activities as a cendrawasih (bird-of-paradise) specimen collector and his cousin offered to take me deep into his forest-garden on the limestone hill where the Red Bird-of-Paradise (which Wallace collected) often visited. We left before dawn, so as not to disturb the birds and after a one hour trek the sun was bursting above the sea as we reached the spot where the birds ‘played’ before disappearing into the forest to forage. Our guide pointed up to the dark leaves – we could see a male’s red plumes bounce from branch to branch, as well as its corkscrew tail wires. It must have been a thrilling sight for Wallace who had struggled to obtain more than two birds-of-paradise back on the island of Waigeo. In an era before film and photography, specimen collection was vital for scientific research and so

Wallace moved to Bessir (now Yenbeser) on Gam island where “eight or ten” of the men were experts in the art of ensnaring and preserving birds.

As we returned to the village, my friend’s wife had cooked fresh fish with rice over a wood fire. Drinking water was retrieved from a well and boiled. Puppies sniffed our feet as we savoured the lime sambal and a monitor lizard shot across the nearby beach towards a coconut tree. But as we enjoyed our food, I thought of Wallace who struggled to eat on the island: “The vegetables and fruit in the plantations around us did not suffice for the wants of the inhabitants, and were almost always… gathered before they were ripe. It was very rarely we could purchase a little fish; fowls there were none; and we were reduced to live upon tough pigeons and cockatoos, with our rice and sago, and sometimes we could not get these.” As his health deteriorated, he was forced to forage – eventually finding some wild tomatoes, pumpkins and ferns.

As we returned to the village, my friend’s wife had cooked fresh fish with rice over a wood fire. Drinking water was retrieved from a well and boiled. Puppies sniffed our feet as we savoured the lime sambal and a monitor lizard shot across the nearby beach towards a coconut tree. But as we enjoyed our food, I thought of Wallace who struggled to eat on the island: “The vegetables and fruit in the plantations around us did not suffice for the wants of the inhabitants, and were almost always… gathered before they were ripe. It was very rarely we could purchase a little fish; fowls there were none; and we were reduced to live upon tough pigeons and cockatoos, with our rice and sago, and sometimes we could not get these.” As his health deteriorated, he was forced to forage – eventually finding some wild tomatoes, pumpkins and ferns.

His book The Malay Archipelago is also a fascinating account of the people of Indonesia in the nineteenth century, and Wallace spoke fondly of the “honest” villagers of Bessir who housed him in a stilted hut next to white sand – a “dwarf’s house, just eight feet square” which he cleaned and stayed in for six weeks with his crew and “none of us grumbled at our lodgings.”

It is interesting to see how he perceived this magical archipelago over one hundred years ago. Already, in places such as Ternate and Raja Ampat, the locals still cherish their connections with Wallace, but hopefully he will be recognised beyond Indonesia and scientific circles and reach a larger audience across the world. So, in this centenary year of his death I raise a glass to the great naturalist Wallace and hope that his theories and adventures inspire future generations to come.

Further Information

Wallace, Alfred Russell, (1869) The Malay Archipelago, Macmillan: London

The A.R. Wallace correspondence project: http://wallaceletters.info/

Bill Bailey’s two-part documentary: Bill Bailey’s Jungle Hero, Wallace in Borneo and Wallace in the Spice Islands