With the news that 11-year-old Indonesian pianist Joey Alexander’s first album, My Favourite Things, topped the jazz charts in the first week of release, the Indonesian jazz scene seems to be in quite a good place in the jazz firmament.

Joey is undeniably an incredible talent, a prodigy as confirmed when I saw him in concert in 2013. Much is made of his extreme youth but sadly for us, Joey has been fast-tracked for an O-1 visa “for individuals with an extraordinary ability” and can no longer be regarded as Indonesian.

However, there have been, and are, many outstanding jazz musicians here. In the 50s, Bubi Chen (1938–2012), the pianist widely recognised as the ‘Godfather’ of Indonesian jazz, spent two years in the USA studying jazz piano under the tutelage of Teddy Wilson, sometimes accompanist for Billie Holiday. Two young drummers, Demas Narawangsa and Sandy Winarta are currently studying jazz in the USA; pianist Nial Djuliarso studied at both Juilliard and Berklee College of Music. Moreover, several talented musicians, such as Sri Hanuraga, Adra Karim and Elfa Zulham, have completed their jazz studies at European universities. Indonesian jazz is a tale of generations, politics and class structure, a history as yet untold.

I arrived in Jakarta at the tail end of 1987 and as an inveterate seeker of jazz, progressive rock and ‘world music’, I soon discovered the pirate cassette scene. I travelled widely through the archipelago in my pre-family days, from North Sumatra to the Molluccas, and made a point of collecting cassettes recorded locally. I came to appreciate that each region had its own music traditions, with a range of particular instruments, often including electric keyboards. I also discovered that such jazz as existed appeared to be formulaic; piano, guitar, bass, drums and maybe saxophone, backing a pop singer whose melodies and lyrics, with the word ‘cinta‘ sprinkled generously throughout, were invariably sugary.

According to Professor Royke Koapaha at Yogya ISI, in the 50s and 60s classical music was considered high class and jazz “low class”; to be caught playing it invited scorn. There was also President Sukarno’s mid-sixties ‘war against the Beatles’ and other western influenced music. Was the jazz I was hearing ‘subversive’?

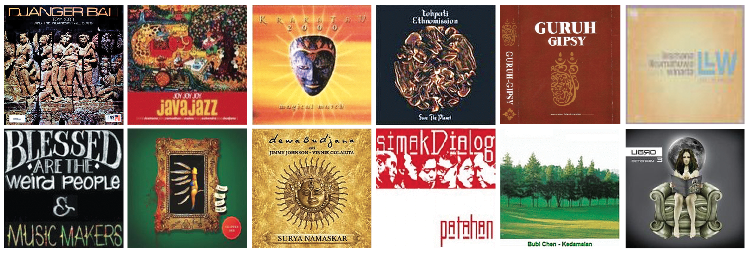

Soeharto’s accession to the presidential seat in 1966 let the shackles off anti-west sentiments. The following year, having played at a jazz festival in Europe, the Indonesian All-Stars, comprising Bubi Chen on piano and kecapi (Sundanese zither) Jack ‘Lemmers’ Lesmana (guitar), Marjono, saxophonist and suling (bamboo flute), Jopie Chen (bass), and Benny Mustapha van Diest (drums), recorded an album in Austria with Tony Scott, the American jazz clarinettist and arranger. Djanger Bali is now recognised as a seminal album in Indonesian jazz history.

After that, there appears to have been a lull in the jazz scene. Psychedelic music captured imaginations for a while, and then Jack Lesmana is credited with introducing jazz rock music in the early 70s. This was followed by a prog-rock scene which has lasted to this day. Notable names included Sukarno’s son, Guruh, who, in 1976, played gamelan on a recording with a group called Gypsy; the album, Guruh Gypsy, is now regarded as a classic.

In 1989, ethno-jazz re-emerged. Bubi Chen, “credited with adding an Indonesian flavour to jazz music especially at a time when President Sukarno despised western music”, may have been the catalyst with the release of his cassette only album, Kedamaian. Accompanied by zither and bamboo flute, his playing flows over Sundanese melodies. In the early 90s, Krakatau, a fusion jazz group led by classically trained pianist Dwiki Dharmawan, incorporated Sundanese percussion and wind instruments, with western instruments tuned to slendro and pelog scales. The group Java Jazz, formed by keyboardist Indra Lesmana, son of Jack, was to follow suit. Balinese guitarist Dewa Budjana, mentored by Indra, replaced the deceased saxophonist Embong, and the group forged a catalogue of tunes based not only on technical ability and melodic sense but also their different ethnic backgrounds.

The first JakJazz festival in 1988, coordinated by guitarist Ireng Maulana, was notable for easy listening artists such as Lee Ritenour and Phil Perry, with but a few truly creative groups such as Itchy Fingers from the UK and Kazumi Watanabe from Japan. Ten years later, President Habibie’s initiative to dissolve the Ministry of Communication may have been the trigger which released jazz, the music of creative improvisation, of play. With access to the Internet and the growth in Indonesia’s economy since then, ‘jazz cafes’ have proliferated urban centres and festivals are held throughout the archipelago. Universities and music schools have established jazz departments staffed by professional musicians, many of whom were mentored by their ‘seniors’.

Jazz is about community, not about individual celebrity status, and mentoring through the generations has been a notable feature of its current dynamism, for example: Jack Lesmana to Indra to Eva Celia; Benny to Barry and Utha Likumahuwa. Riza Arshad, founder of ethno-jazz group simakDialog, says that he is particularly proud to have played with Bubi Chen. Riza also studied with Jack and Indra Lesmana; and in turn he has mentored pianists Joey Alexander and Sri Hanuraga.

Recently, a few artists such as simakDialog, Dewa Budjana, and Tohpati have had self-produced albums released internationally on the MoonJune label based in New York. They have also recorded albums in the USA with A-list western jazz musicians. What is particularly encouraging is the release on MoonJune of self-produced albums by I Know You Well Miss Clara, Tesla Manaf and the power trio Ligro, who truly stretch the genre’s boundaries. However, few local jazz musicians have an outlet other than occasional gigs where fans can buy recordings.

IndoJazzia has been established to support the Indonesian jazz community at large by offering access to information and resources on a communal basis.

The website (http://indojazzia.net) also offers a portal to the many musicians seeking international exposure as well as jazz aficionados abroad newly aware of the astonishing creativity to be discovered here.

A start has also been made on a major project: ‘The History of Indonesian Jazz’. With early pioneers reaching the evening of their days, this is intended to be an audio visual documentary and book, with the possibility of the release of hitherto non-digitalised albums, concert tours and other associated activities.

We welcome all contributions. Please contact us via email: admin@indojazzia.net