Meet Jacob Vredenbregt. The humanitarian, educator, and art collector from the Netherlands.

Somewhere hidden in Ciputat is a walled estate. Inside the estate is a set of unique buildings surrounded by orchards and ponds. It is a hidden jungle in the metropolis, given back to Mother Nature. “I bought this land, gave it water and plants and let nature have its way with it,” says Jacob Vredenbregt.

Shortly after the Second World War in Europe had ended, Jacob applied for voluntary service and was eventually sent to Indonesia to fight for the Netherlands in its attempt to reinstate the country as a colony after Japan had annexed it in 1942 and left it after the war. A long journey in a crowded boat followed and the first land he set foot on was Tanjung Priok, North Jakarta. They stayed there for two days and moved on to their final destination, Surabaya.

Not long after arriving in Indonesia he was shot and captured as a prisoner of war. Peculiarly, this is the time in which he fell in love with the culture and its people. Regardless of his status as a prisoner, he had considerable freedom at certain times, which allowed him to converse with locals and learn the language.

After being released and upon his return to the Netherlands, he was already convinced to go back to Indonesia, emotionally touched by the way he was treated. So when he was asked to interrupt his law study at the University of Utrecht and return to Indonesia to provide jurisprudence for an agricultural conglomerate, it was not a difficult matter.

The new government of the Republic of Indonesia had laws and regulations written in Bahasa Indonesia and they could not find anyone in Indonesia who could read and apply these accordingly. He soon became a protector of the working class, because most of them were not familiar with the new collective labour agreement and thus easily manipulated.

“The communists of the time had no intentions to better the work conditions of labourers,” says Jacob, “they were out to destroy the companies and reinstate them according to true Marxism.”

Due to his knowledge of the law, his drive for justice, and literary experience with Karl Marx,the labourers finally got the salary they deserved. “Of course, in the end I was the one who lost. They didn’t renew my visa and I had to return to the Netherlands,” utters a mournful Jacob.

Meanwhile, he had managed some amazing achievements. Jacob firmly believed in education for everyone and made it compulsory for all the children of the employees within the companies he worked for to attend school. Buildings were erected to provide classrooms and teachers were drawn. Thanks to Jacob thousands of children were educated, an incredibly valuable asset to the local communities.

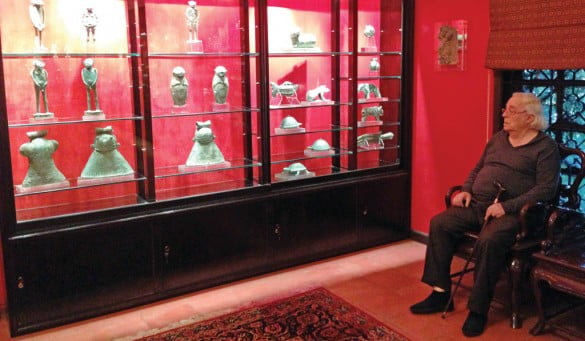

His second love had sprouted during his second stay in Indonesia. During his subsequent visits to towns and villages, he came across various special works of art and not only started collecting these, he also made an effort to know what they were and why they were special. It could have been a stroke of luck or wisdom, but he managed to buy items which increased in value dramatically over the years, making it easier to expand the collection with a wide variety of special and valuable items.

Back in the Netherlands, he decided not to finish his previous law study and enrolled in cultural anthropology at Leiden University. “I had enough of law and was far more interested in the immensely diverse culture in Indonesia. This made it much more logical for me to study anthropology and non-Western sociology and I chose Southeast Asia as a broader area, with Indonesia in particular.”

After five years of dedicated studying, Jacob had to write a thesis and his choice fell on a tiny ethnic group on the island of Bawean, off the coast of Java. Finally he was able to return to his great love; Indonesia.

Due to the political unrest in 1965/66 Jacob was forced to return to the Netherlands, yet again against his own will. He still had to finish his thesis and was allowed to defend his findings in the summer of ’68. After becoming Dr. Jacob Vredenbregt he left Europe again, but this time it would finally be for good.

Jacob had a fruitful career as a teacher at multiple universities in Indonesia. He taught in English and Bahasa Indonesia, wrote a dozen literary novels and scientific books, stayed in Vietnam and Cambodia for a while and finally decided to settle down in Ciputat, Jakarta. He bought an empty plot, designed a spacious house and surrounding garden and still lives there to this day.

Nowadays his art collection is jaw-dropping, featuring paintings, statuettes, figurines, instruments and ornaments. Whenever he was travelling through Southeast Asia there would always be spare time to look for art. He bought whatever he liked, making his collection incredibly diverse, unique, and worthwhile to look at. The most amazing thing is that every object has its own story, and Jacob remembers them all. At the respectful age of 87, he still comes across as witty and vivid.

“The government is planning to place a new road right through my land and they’re buying me out. I’ll have to move soon, but I don’t have a new place yet,” Jacob says. When asked if he is sad to move from his old house in Ciputat he says, “No, of course not. I see it as my next adventure. I enjoy every day while I’m still young.”