Nowadays Kemang is a favourite residential area of foreigners, and a trendy hangout hotspot with a wide range of restaurants, bars and cafés. Not so long ago it was a collection of hamlets or possibly a single sparsely populated village inhabited by orang Betawi. The area was pleasantly green and airy because of its fruit orchards and paddy fields.

That was some 40 years ago. Since then Kemang has gentrified. That is, the original inhabitants sold the land, parcel by parcel, to finance a hajj or another marriage. Trees were cut and sawahs (rice fields) filled, and modern houses appeared that were rented out to foreigners.

Ibu Titi, who provided me with information on Kemang and the Betawi, seemed a little sad. She was born in Kemang and witnessed these changes personally. After selling most of her family’s land, she now lives in a house on the edge of Kemang, a house that regularly floods after heavy rains and the overtopping of the nearby Mampang River. The flooding only started after the construction of the large apartment complex across the river—the floodplain that previously had been an empty space where her sons played football. She does however agree that selling the land enabled her to pay for the education of her children and to go on a hajj.

Kemang is also the area where I saw the Betawi ondel-ondel—large 2.5 meter-tall figures with a headdress made from dried coconut leaves that have been shredded lengthways and wrapped with colourful paper. When I saw them for the first time I found them rather frightening. Maybe because it brought back scary childhood memories of Der Struwwelpeter (Shockheaded Peter), a German children’s book written in 1845 by Heinrich Hoffmann. The book’s ten stories and illustrations tell children not to be naughty to avoid dreadful punishments.

The book’s title story is about a boy who refuses to brush his hair and cut his nails. Unkempt, he is then shunned by all. The book’s illustration of Peter came to mind when I saw my first ondel-ondel. I was glad to hear that Ibu Titi’s daughter was also scared of these Betawi puppets. Ondel-ondel typically appear in pairs, the red-faced male accompanied by a female with a white face. Traditionally the figures were paraded to protect villages from evil spirits and disasters and to solicit opium. However, when opium use was forbidden by the colonial administration, the ondel-ondel dancers started asking for money.

Since Indonesia’s independence and especially since the administration of Jakarta Governor Ali Sadikin (1966-1977), the ondel-ondel have become the mascot of Jakarta and a standard part of official celebrations, weddings and the welcoming of guests of honour. In 2009, a large set of ondel-ondel was prepared to welcome the Manchester United football team. Each of the dummies had a sash with the name of a player draped over its shoulder. The team unfortunately canceled its visit and a match against a selection of Indonesian players after the JW Marriott hotel bomb blast.

There are Betawi people, the Betawi village of Kemang, and the ondel-ondel—a prominent side of the traditional Betawi culture; but who are these orang Betawi?

The region that is now Greater Jakarta was a part of the Tarumanagar Kingdom from the fourth to seventh centuries. For the next six hundred years it was ruled by the Sunda Kingdom and, in 1527, General Fatahillah of the Demak Kingdom conquered the settlement where the Portuguese had established a post and renamed the town Jayakarta. The Dutch arrived in 1596 and were granted permission to build a trading post. In 1617, Jan Pietszoon Coen built a second lodge, and the Dutch were ousted by the ruler of Jayakarta with the help of the British who eagerly provided this service. Coen returned in 1619 and razed the town of Jayakarta. On its ashes, Batavia was built.

The name Betawi is derived from Batavia. It is therefore not surprising that under the previous kingdoms the area’s inhabitants were never identified as Betawi—the word didn’t exist yet. Those who migrated into the area were identified by their original ethnicity: Javanese, Sunda, Balinese, Makassar, and the like.

The Betawi are thus the most recently formed ethnic group in Indonesia and consist of a mixture of Javanese, Sunda, Malay, Ambonese, Bugis, Makassar, Arabs, Chinese and other non-Indonesians. For many inhabitants of Batavia their original ethnic roots have been lost over generations due to progressive creolisation.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the Batavians started to call themselves orang Betawi. The new group was officially recognised in 1930 and the Batavia population census of that year included a column Betawi.

The many loan-words in the Betawi language, unsurprisingly, reflect these different influences. It is now a very popular informal language among urban youngsters, but because it is perceived as a rough and not very polite language, Ibu Titi and her family and many other people nowadays prefer to speak Indonesian at home.

Betawi cuisine stands out and is decidedly tasty. Betawi specialities are widely available as they are sold by the ubiquitous street vendors. For those who are hesitant to try the food from the kaki lima carts, a restaurant in South Jakarta offering a wide variety of Betawi food is Boplo on Jalan Panglima Polim IX. The restaurant has branches in different parts of the city as well.

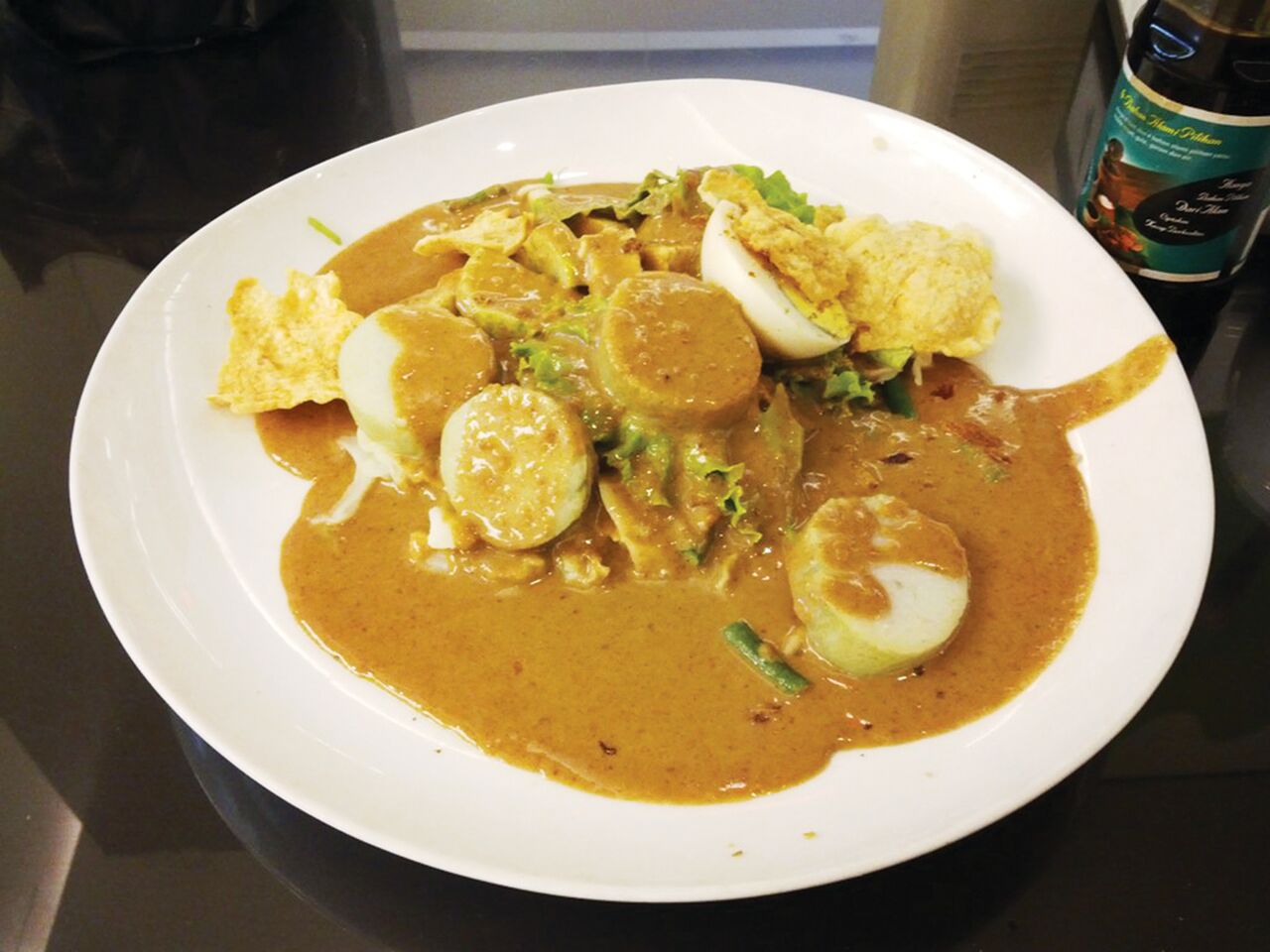

Boplo is famous for its gado-gado, a salad à la Betawi with a spicy sauce made of peanut, garlic, palm sugar, chillies, salt, and toasted shrimp paste. Their Soto Betawi is also worth a try. This soto (soup) is different from, for instance, soto ayam as coconut milk (santan) is used in the soup.

Another special Betawi delicacy is kerak telor, an omelette with sticky rice which is sprinkled with sweet grated coconut, dried salted shrimp and fried shallots.

But don’t forget to try ketoprak-lontong (rice steamed in a banana leaf) with vermicelli, tofu and bean sprouts in a peanut sauce; its spiciness to be decided by the customer. Most of the above dishes are accompanied by deep-fried prawn or shrimp crackers.