“This is my earthly life, full of trouble and struggle, and many are my enemies, laughing at me…their words sharper than the Kris… Thou shall lift me up and again I will speak and fight. And then my enemies will be silenced and the demon will crash down. Lord, let me be a Wayang in your hands.”

Raden Mas Noto Soeroto, Wayang Songs, 1931

In 1913, Prince Noto Soeroto, a poet-prince of Jogjakarta, published a since long forgotten article in the first edition of Indonesia’s premier architectural magazine, The Dutch East Indies Home; Old and New (Het Nederlandsche Indische Huis Oud en Nieuw) dedicated to Pak Iko, an unknown Indonesian sculptor. Although the style is hopelessly flowery by today’s standards, its core message, the acknowledgement of the thousands of anonymous Indonesian artists, artisans and craftspeople, who carry on the nation’s ancient artistic traditions is as relevant today as it was a century ago. Soeroto begins his story with a eulogy:

In 1913, Prince Noto Soeroto, a poet-prince of Jogjakarta, published a since long forgotten article in the first edition of Indonesia’s premier architectural magazine, The Dutch East Indies Home; Old and New (Het Nederlandsche Indische Huis Oud en Nieuw) dedicated to Pak Iko, an unknown Indonesian sculptor. Although the style is hopelessly flowery by today’s standards, its core message, the acknowledgement of the thousands of anonymous Indonesian artists, artisans and craftspeople, who carry on the nation’s ancient artistic traditions is as relevant today as it was a century ago. Soeroto begins his story with a eulogy:

“Few will know who or what Iko is. Iko is one of the many who hide behind their art unaware of their privilege to serve their fellow humans through the creation of beautiful things”.

The reader quickly learns that Iko did not spring out of nothingness. Towards the end of the 19th century a growing number of aficionados began raising the alarm that the traditional arts of the Dutch East Indies were in severe decline for a variety of reasons. Their revival would become a celebrity cause among a small but elite group of scholars, administrators, ethnographers, artists, architects, collectors, Javanese royalty and colonial officials who set up such institutions as the Java Institute in Jogjakarta (its collection is now the Sonobudoyo Museum). The movement was also affiliated with the newly instituted “Ethical Policy”. Promoted by the newly elected Socialist government, the first in Holland’s history, it was based on the conviction that Dutch had a historic and ethical responsibility to educate and modernize their colony and subjects.

A sentiment better known in English as “The White Man’s Burden”, the title of a poem written by Rudyard Kipling in 1899, the noble cause was, of course, ethnocentric and paternalistic foremost because its premise was still mired in racial and cultural bias, the intrinsically evil premise upon which colonialism was founded. While colonialism remains indefensible, this does not discredit the many who played positive roles, in this case support of several grand traditions that might not have survived without their intervention. Two of the most notable successes that are still alive today are the silversmiths of Kota Gede, Java and Bali.

Unlike today’s many pundits who drone endlessly about the need to preserve culture and heritage with little or no knowledge of what is traditional or new, much less any workable plan to save them, the colonial government understood that any program to save the arts must begin with an expansive in-depth study of the arts and honest assessment of their current condition. Perhaps the greatest achievement to this end was the massive five-volume work Inlandsche Kunstnijvigheid in Nederlandsche Indië (the Domestic Arts of the Dutch East Indies, 1911-1930). Its two authors, the enlightened colonial administrator and art lover, J. E. Jasper, and partner M. Pirngadie, a Javanese artist, are among the great heroes of the movement. While, the books are, like Noto Soeroto’s article, dated, they not only served as the basis for developing effective programs to support traditional arts and artists but also still stand as pioneering standard works on the subject.

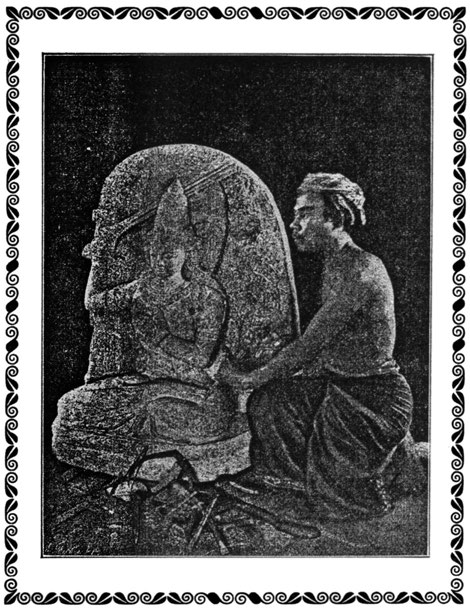

The story of Iko is illustrative of the spirit of the times. A young Sundanese sculptor, his talent was first noticed in 1905 by C. den Hamer, an official in the department of native education who strongly believed in promoting local arts. Over a period of years Hamer asked Iko to produce gradually more complicated artworks. This would culminate with a commission to recreate a life-size statue of Manjushri, the Mahayana Buddha of the Future. Its inspiration was one of the great masterpieces of the Majapahit Empire carved in 1343 and installed in Candi Jago in East Java. In 1861 it disappeared and ended up a few years later in the Berlin Museum. Iko’s model was a plaster cast that can still be seen in Jakarta’s National Museum. Tragically the original was either lost or destroyed in the Second World War.

The story of Iko is illustrative of the spirit of the times. A young Sundanese sculptor, his talent was first noticed in 1905 by C. den Hamer, an official in the department of native education who strongly believed in promoting local arts. Over a period of years Hamer asked Iko to produce gradually more complicated artworks. This would culminate with a commission to recreate a life-size statue of Manjushri, the Mahayana Buddha of the Future. Its inspiration was one of the great masterpieces of the Majapahit Empire carved in 1343 and installed in Candi Jago in East Java. In 1861 it disappeared and ended up a few years later in the Berlin Museum. Iko’s model was a plaster cast that can still be seen in Jakarta’s National Museum. Tragically the original was either lost or destroyed in the Second World War.

Iko set out with great vigour to recreate one of the chef d’oeuvres of Javanese art and succeeded magnificently. A crowned Manjushri sits it lotus asana calmly meditating with his eyes cast down to a vajra he grasps in his left hand before his heart cakra. His upheld right arm brandishes a long doubled edge sword above his head and behind his back. His lithe, muscled torso leans slightly to the right to balance the sword and create movement. Utmost calm and active engagement and the rapture of the Buddha’s imminent return are expressed with elegance and grace.

As in meditation Iko walked a troublesome path to reach his goal. The large piece of teak, we are told, split from internal fissures early on creating obstacles. Courageous and humble, Iko stayed the course until completion. Hamer was so pleased that he drew the attention of his circle of friends and acquaintances, both the sculpture and its maker. Iko would receive the ultimate contemporary honour for the magnificent statue which was offered as a gift to Wilhelmina Queen of the Netherlands and the Empress of the Dutch East Indies by J. H. Abendanon. It is still in the royal collection. In the words of Noto Soeroto it was, “A simple gift in the service of Art”.

After the article and honour Iko once again faded into the same anonymity that cloaks the thousands of Indonesian artisans like him. The next time you look at the stunning carvings, tapestries and artworks seen in many of Indonesia’s best hotels and restaurants or even your own home, stop and think about the person who made it as well as the humble circumstances and simple tools that dominate cottage industries. Remember too that the greatest of these artists often live difficult lives. In comparison, the great artisans of Japan are anointed “National Treasures”, a title that guarantees prosperity, honour and fame.

As one of the world’s greatest and last reservoirs of traditional arts and artisans, Indonesia has an important role to play on the world stage in the post-industrial age. So, too, handicraft and cheap wares pumped out for the likes of Pier One must be distinguished from the masters of their craft. It is time to stop talking about heritage and do something about it. The first step is to follow in the footsteps of Jasper and Pirngadie and embark on careful studies and assessments of the current situation. Identifying and honouring the creators of these ancient arts in the same manner as contemporary artists is a pre-requisite of their survival and success.