The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Conference of the Parties, 20th Session (UNFCCC COP 20) was held in Lima, Peru, during the first half of December 2014. The results of the conference offer a glimmer of hope for the future.

At present the world has warmed 0.8°C since pre-industrial levels (1750). It is, however, predicted that under current conditions, the increase could reach 4°C. The results of the Lima conference do, however, offer hope. The delegates from the nearly 200 countries and territories that attended have agreed on a framework for setting national pledges to achieving a global climate deal at next year’s summit in Paris.

The main stumbling block remains the financing of the programme. The richer nations are not only requested to lead the way in making cuts in emissions, but also to help finance the programmes of the developing countries—the agreement calls for “developed countries to provide financial support to “vulnerable” developing nations”.

At a global scale, the key greenhouse gases resulting from human activities are: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases (F-gases). Methane and nitrous oxide are mainly caused by agricultural activities, while fluorinated gases result from industrial processes and the use of a variety of consumer products. But the main contributor to greenhouse gases is CO2. The way in which land is used is also an important source of carbon dioxide (17%), especially when it involves deforestation and degradation of land, like the draining of peat swamps.

Forests and land can also absorb CO2 through reforestation, improvement of soils and landscapes, and other similar activities. It is in respect of this land use and forestry-related carbon dioxide emission that Indonesia has an important role to play.

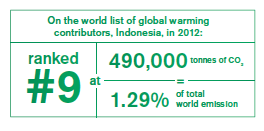

On the world list of global warming contributors (2012), Indonesia ranked ninth at 490,000 tonnes of CO2, or 1.29% of total world emission. It can be safely assumed that these emissions are mainly due to deforestation and changes in land use, rather than the burning of fossil fuels. The numbers one and two in the world emission rankings—China and America—contributed 24.65% and 16.16% respectively, mainly due to their burning of fossil fuels for the generation of electricity and transportation.

Global emissions in 2012 resulted in a concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere of 397 parts per million (ppm), or a 43% increase over the pre-industrial level of 278 ppm. The current annual increase in CO2 concentrations is about 2.2 ppm. This means that the CO2 concentrations will exceed 400 ppm this year or next. And 400 ppm constitutes a threshold. Contrary to earlier climate models, which assumed that concentrations below 550 ppm would—with a relatively high certainty—limit global warming to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, recent climate research argues that the 2°C limit can only be reached when concentrations are kept below 400 ppm. Heated arguments about the projected levels of these concentrations and their effect on global warming are continuing unabated.

One of the programmes designed to reduce Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions, therefore significantly contribute to a reduction in global warming is REDD+ (Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation, with the “+” standing for sustainable management of forests, and conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks). This partnership programme has been concluded with Norway and provides financial rewards, initially USD1 billion, for Indonesia’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Payment will depend on verification of the efforts and corroboration of the results achieved.

The first phase of REDD+ was the collection of data in nine pilot provinces. Progress has been much slower than initially projected; currently the achievements have drawn down less than 5% of the total pledged, caused by bureaucratic red tape and confusion when new projects are initiated, combined with a lack of direction and prescriptions on how to implement a programme of this magnitude and complexity.

Anto Haryuatmanto, GM of PT Waindo SpecTerra, a company specialising in spatial information, informed me that the main difficulty is the lack of a map that is accepted by every stakeholder as representing the actual situation on the ground. Maps differ in respect of land use and vegetation cover, forest boundaries, watersheds, and road alignments. Consequently, authorities and agencies at national, provincial and district level do not accept the maps used by their peers, or the maps used by their technical counterparts at other levels, each stakeholder insisting that its version is the correct one.

Conflicts, such as overlaps of conservation forests and oil palm estate permits, are thus insolvable. As the map shows, forests—only 50 years ago covering 90% of Sumatra and Kalimantan—have been squeezed out.

When contracted for the REDD+ pilot project in the province of Riau, Waindo SpecTerra started with producing a new and highly accurate map for each district, using remotely-sensed data and GPS-supported ground verifications. Detailed discussions were then held in the districts to explain the techniques and methodology used to produce the maps. Juxtaposing the existing maps with the new one and highlighting the differences quickly led to an acceptance of the new map.

A second obstacle remains, which could be described as the absence of political will. REDD+ directly involves a fairly large number of stakeholders: 1) government authorities at all levels from Jakarta to the villages, 2) agro-estates, 3) logging companies, 4) smallholder farmers, and 5) indigenous forest dwellers. The first four generally prefer a dead tree to a living one, because a tree, once felled, can be sold for timber, burned to make room for plantation crops and the expansion of smallholdings. Indigenous forest dwellers are the only ones with an interest in preserving the forests. Their voices are, unfortunately, hard to hear, as the money is in the other camp. The REDD+ compensation for leaving a tree standing will thus be weighed against the profits derived from cutting it down.

During the next phase of REDD+ the amount paid as compensation [per hectare] for not disturbing forest and land will need to be set with the extractive uses in mind.

For more info, visit www.reddplus.go.id