There are a number of versions to this story. Depending on the narrator, the good people of Batavia were saved from a horrendous fate, or the matrix, the super system if you wish, rids itself of the awkward outsider and troublemaker. But whatever the twist given by the chroniclers, the storyline is simple: Pieter Erberveld was accused, convicted and executed.

He was the son of a German father and a native mother—some sources refer to her as a Christian Thai, while others maintain she was Indonesian. His father had come to Batavia and had started a leather tanning business. After having been appointed by the VOC (Dutch East Indies Company) as advisor on cadastral matters for the Ancol area of North Batavia, he became a landed burgher. That sounds better than it actually was, as in early 18th century Batavia, a freeman, however affluent, was about the lowest rung of the expat ladder.

The estate of several hundred hectares was left to his son, the unfortunate Pieter.

At this point we will need to separate the twists and follow them one by one. My sympathy goes to Pieter Erberveld, the victim of the powers that be, the powers that usually get what they want.

So this is the sad story where Pieter Erberveld is made the victim.

Governor-General Joan van Hoorn expressed the wish to purchase the estate Pieter had inherited. When he refused to sell his land, it was expropriated on the grounds that the papers were not in order. Simple.

He must have protested loudly and persistently because, in the end, that is some ten years after the expropriation, the VOC finally got fed up and accused him of a conspiracy to oust the VOC, massacre all expatriates of Caucasian descent, and proclaim himself Overlord of Batavia. This coup d’état was supposed to take place on New Year’s Eve 1721. Apparently the authorities had been informed of the conspiracy by a slave from Erberveld’s own household, and they reacted with speed.

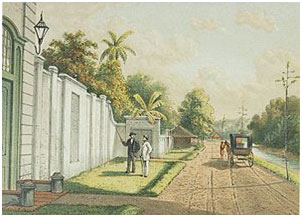

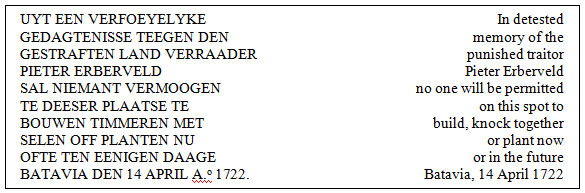

Erberveld and his co-conspirators—Raden Ateng Kartadriya, a functionary from Banten, and Layek, a young man from Sumbawa—together with 17 others were apprehended, tortured and convicted. The verdict was death, and in the case of Pieter Erberveld this was to be a rather protracted affair. He was drawn and quartered, and beheaded after his heart and other internal organs had been ripped out. His head was subsequently impaled on top of a wall erected in front of his old house, with the following inscription as a warning to possible sympathisers:

That, of course, was the official line. But, for the past 300 odd years a fair amount of questions have been raised as to the actual full facts of the case. Also from the Dutch side, and even long before Indonesia became independent.

The main question still to be answered (answers will not be found, by the way, as the relevant documents related to the case have been lost) is: why would Pieter Erberveld want to do that?

More than ten years after having been defrauded by the VOC, suddenly planning mass murder… to get even!

Another question waiting for an explanation is: would the authorities take immediate action on the words of a slave? And who was that slave anyway? The answer to the former is “probably not”. Bureaucracies, even those of private trading houses, are not known to make quick decisions, and here we are talking about the 18th century! People were used to life in the slow lane—a letter to HQ would take 6-8 months, a reply could thus be expected after one-and-half years. Wouldn’t they be suspicious and want to check why a slave suddenly denounced the master?

The information about the identity of the slave is even more confusing. One story is that the slave, Ali, wanted to marry Sarina from the same household, but the master, Pieter Erberveld, did not approve. It was said that Sarina was his own daughter and he didn’t want her to marry a slave. Another version is that she was his bed-warmer, and he didn’t want to lose her. Ali, angry and disappointed, is then supposed to have contacted the security apparatus, while yet another version maintains that it was Sarina who relayed the information… Again, why? Because she was not allowed to marry Ali who wanted to make an upright woman of her! Sounds implausible.

In Indonesia Pieter Erberveld has reached a semi-hero status and is used to illustrate the wickedness of the colonisers and the early efforts to gain independence.

I myself see him in a wider and ongoing context: the limitations of the individual and the systemic power of the matrix. Think in terms of John Lennon’s Working Class Hero. … “as soon as you’re born they make you feel small / by giving you no time instead of it all…”

The Pieter Erberveld memorial was destroyed during the Japanese occupation, but the commemo-rative tablet with the inscription was saved. A replica can be seen in the Museum Taman Prasasti, at Jl. Tanah Abang 1. Check it out, it’s a wonderful experience.