Through the window of early photography, Scott Merrillees has brought the long lost world of Jakarta back to life in his book, BATAVIA in Nineteenth Century Photographs, which presents the most comprehensive photographic record ever published of the city from the late 1850s, when the earliest known photographs were taken through to the closing years of the 19th century.

Published by Southeast Asia specialist, Archipelago Press, an imprint of Singapore-based Editions Didier Millet, the book’s 155 rare photographs – many never before published – were sourced from leading institutional and private collections in Europe and Australia and from the author’s personal collection, all carefully reproduced in original sepia tone.

The sophisticated photographs found in this volume are all the more surprising, considering that they were taken during the age of the wet collodion plate, a thin piece of glass coated with a wet and sticky chemical emulsion that was sensitive to light. The glass plates were a very early form of photographic “negative” and are now almost non-existent and impossible to find. They often broke because they were very thin and fragile or were wiped clean by the photographer so they could be re-used. The glass plate negatives were used to print photographs on very thin paper coated with a solution, including egg whites (i.e. “albumen”) and thus were known as “albumen prints”.

Reproduction quality and clarity are so detailed that you can make out pebbles, shadows and tire marks on the road, ripples and reflections on water, blades of grass along a pathway and the leaves of trees finely etched against the sky. In an 1880 photo of the Museum of the Batavian Society of the Arts and Sciences, the present-day National Museum, the open windows without bars reveal priceless collections visible inside.

Of particular note are the captivating albumen prints from the Woodbury & Page collection, which includes images of Batavia’s landscape and colonial buildings. Working in partnership, Walter Woodbury and James Page established a photographic firm in 1857 that continued to produce and sell images long after Woodbury’s return to England in 1863, and Page’s untimely death in 1865.

Extensively researched, the meticulous annotations are remarkable because in this early period, photographs were very seldom dated. Determining a date to a scene required voluminous and maddeningly difficult research. The author excerpts eyewitness accounts from travelogues, photo albums, logbooks, ship passengers, financial reports, contemporary magazines, newspapers, lexicons and biographies in English, Dutch, French and Indonesian.

Extensively researched, the meticulous annotations are remarkable because in this early period, photographs were very seldom dated. Determining a date to a scene required voluminous and maddeningly difficult research. The author excerpts eyewitness accounts from travelogues, photo albums, logbooks, ship passengers, financial reports, contemporary magazines, newspapers, lexicons and biographies in English, Dutch, French and Indonesian.

Notwithstanding the exponential and unchecked expansion of today’s megacity, an unexpectedly high number of Batavia’s 19th century landmarks survive to the present day, although the structures have often been completely rebuilt, roofs reshaped and ornamentation eliminated over the last 150 years; the Chicken Market Bridge over Kali Besar in Kota, the Portuguese Church on Jl. Pangeran Jayakarta, Jakarta’s oldest building still used for its original purpose, and the Yin De Yuan temple on Jl. Kemenangan, one of the oldest surviving Chinese temples in Jakarta. It would be fascinating to see these old buildings in “before and after” format placed adjacent to the same scene today.

In one photograph of Koningsplein (today’s Medan Merdeka), the reader can almost feel a refreshing breeze blowing unimpeded across the huge open empty grassy plain, an area so gigantic that it took 1.5 hours to walk around. In those days, visitors even complained that the city was spread over so large an area that it was “uncozy,” lacked “cohesion” and that one needed to take horse carriages everywhere because of the great distances that had to be covered!

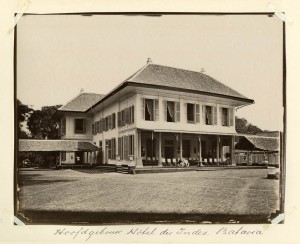

In the chapter entitled Molenvliet (Mill Way), now Jl. Gajah Mada and Jl. Hayam Wuruk, is a wonderful series of portraits of Batavia’s premier 19th century hotels – such as the grand Hotel des Indes – accompanied by details so intimate and kinetic that the reader, looking voyeuristically back in time, can hear the tinkling of china in the bustling dining rooms, the clip clop of horses out in the broad forecourts, the splash of the water fountains in the spacious gardens as orchestra music is carried on the evening breeze. These internationally known hotels were the choice of visiting dignitaries and the centre of splendid functions for the elite of Batavia’s colonial society.

The native population of the time must have been awestruck at the goings-on of the wealthy merchant class and at the imposing colonial edifices with stately white columns and government buildings such as the Stadhuis (Town Hall), now the Jakarta History Museum. With just two exceptions (those of the renowned painter Raden Saleh and his wife), people are not the explicit subjects of the photographs. The overwhelming emphasis in the book is on the topographic and architectural landscape of the city.

The native population of the time must have been awestruck at the goings-on of the wealthy merchant class and at the imposing colonial edifices with stately white columns and government buildings such as the Stadhuis (Town Hall), now the Jakarta History Museum. With just two exceptions (those of the renowned painter Raden Saleh and his wife), people are not the explicit subjects of the photographs. The overwhelming emphasis in the book is on the topographic and architectural landscape of the city.

Unfortunately, many handsome buildings, such as the Harmonie Society club house, completed in 1815 – famous as a venue for grand balls and state functions – were demolished to widen streets or make way for office or shopping complexes. One wonders how much more attractive the city would be today, and what an asset their presence would mean for the tourist industry, had these graceful old edifices been spared.

The photographs are given a deeper dimension in the text with impressions and commentaries from visitors, officials and travellers. We learn of many intriguing insights over the span of decades into how hotels, restaurants, social clubs, haberdasheries, bakeries, watchmakers, jewellers, lavishly appointed shops and department stores came into being, rose to prosperity and ultimately suffered misfortune, their European owners and native staffs disappearing namelessly into the mists of time. The rise and fall of an establishment’s fortunes is often accompanied by a rich chronicle of the lascivious scandals and gossip of the day. Detailed biographies of successful Dutch entrepreneurs as well as the genealogies of their forbears who settled, lived and died in the East Indies through generations are also provided.

Scott Merrillees’ unquenchable curiosity and dedication has resulted in a collection of achingly nostalgic photographs of excellent quality that succeeds admirably – both in image and words – in transporting the reader back to a Jakarta of an earlier age that is now little understood and has largely vanished.