She was promised a well-paying job as a waitress-receptionist in Batam. The establishment, although Chinese-owned, was fully halal, so, no need to worry.

A few weeks later she was “liberated” when the police raided the place and arrested the owner for trafficking.

She was angry. “Prostitution!” she exclaimed. “For that, I could have stayed home! Sialan! And they haven’t paid me a single Rupiah!” She was from Indramayu, a district on the north coast of West Java with a high incidence of prostitution.

I worked in Indramayu many decades ago. Our project guesthouse there was managed by a housekeeper, Didi, who had been a sex worker at some point. She had been recommended by the owner of the house, the Chief of police of the town. She was a good-looking woman in her early forties and a wonderful cook. She had been married when still a teenager. Following local tradition, the wedding took place after a particularly good harvest—Indramayu is one of the country’s rice baskets—and also true to type, her husband divorced her when the money ran out, and after pawning her earrings.

She tried many things, from keeping score and racking the balls in a pool hall, to bridal make-up and outfit rental, but to make ends meet it always ended in prostitution. With the money she had earned as a housekeeper, she opened a little restaurant that hit the mark and slowly grew. First, the interior was renovated, then AC was installed, and finally, she also catered lunches at several government offices.

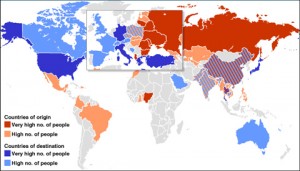

Didi was lucky and cleverly grabbed chances when they presented themselves. I don’t know what happened to the Batam girl. Most likely there are hundreds more like her, trafficked from their home village to Batam or Brunei, Singapore or Seoul. It is of course a global problem, not specifically related to Indramayu. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that at any one time there are some 2.5 million people who have been trafficked and are being subjected to sexual or labour exploitation – not only girls and young women, by the way.

About one-third of trafficked people are boys and men who are used for their labour, for instance as domestic servants, agricultural workers, or others. Two young men, Vietnamese, were recruited to work in a major hotel in London. They borrowed a considerable sum for the journey and the contract arrangements. Upon arrival at Heathrow, the agent took their passports. They worked for two months without receiving a penny. When they eventually protested to management, their families in Vietnam were threatened. Too frightened to contact the Vietnamese Embassy or the police, they finally made it to the Citizens Advice Bureau office via a Vietnamese-speaking person they met on the street. Police, anyway, are often useless as they will insist on documents to prove the identity of the person making a complaint. Without a passport what can you do?

About one-third of trafficked people are boys and men who are used for their labour, for instance as domestic servants, agricultural workers, or others. Two young men, Vietnamese, were recruited to work in a major hotel in London. They borrowed a considerable sum for the journey and the contract arrangements. Upon arrival at Heathrow, the agent took their passports. They worked for two months without receiving a penny. When they eventually protested to management, their families in Vietnam were threatened. Too frightened to contact the Vietnamese Embassy or the police, they finally made it to the Citizens Advice Bureau office via a Vietnamese-speaking person they met on the street. Police, anyway, are often useless as they will insist on documents to prove the identity of the person making a complaint. Without a passport what can you do?

Another form of forced labour is bonded labour or debt bondage. While the least known form of slavery, it is the most widely used method of enslaving people. The ILO estimates that in the Asia-Pacific region alone, some 12 million people are in forced labour, the majority in debt bondage.

Entire families are kept like cattle on farms in India and Pakistan; migrant agricultural workers are forced to remain on ranches in Brazil, and women are forced into domestic and sexual slavery in Europe. The system provides cheap and expendable labour.

Similar to forced labour is descent-based slavery. It is a situation where people are born into a slave class. Typically, people born into slavery are not allowed to own land or inherit property and are denied an education. Any child born is automatically considered ‘property’ of the master and can be given away as gifts or sold. This exists mainly in Mauretania, Niger and Mali.

Similar to forced labour is descent-based slavery. It is a situation where people are born into a slave class. Typically, people born into slavery are not allowed to own land or inherit property and are denied an education. Any child born is automatically considered ‘property’ of the master and can be given away as gifts or sold. This exists mainly in Mauretania, Niger and Mali.

A specific class of slavery is formed by child labour. In most poor societies children are, from an early age, needed to contribute to the family income or provide domestic services that free an older family member to earn an income. Children fetch water, the older ones take care of their younger siblings, herd the livestock, clean in and around the house, and the like.

Millions of children, however, do extremely hazardous work under harmful conditions. They have no chance of receiving any formal education and their personal and social development is severely thwarted. Often they even put their health and even their lives at risk.

Millions of children, however, do extremely hazardous work under harmful conditions. They have no chance of receiving any formal education and their personal and social development is severely thwarted. Often they even put their health and even their lives at risk.

Based on the ILO statistics, some 215 million children, aged between 5 and 17, are considered child labourers; about 115 million of these are found in the hazardous work class, and 8.4 million children are in slavery: debt bondage; child soldiers, prostitution and pornography; and other illicit activities.

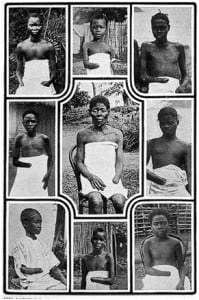

News reports on tribal and regional conflicts in Congo and Uganda always mention child soldiers and the atrocities committed against women. Amputations of hands and feet seem to be a well-established way of intimidating the communities, together of course with rape and murder.

Nothing new here. One hundred years ago the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR) used the same tactics to ensure a constant supply of free labour to collect rubber. The ABIR Company was a company which harvested natural rubber in the Congo Free State, the private property of King Leopold II of Belgium. The company was founded with British and Belgian capital and was based in Belgium.