Many of you reading this will not often consider yourself a type of migrant. ‘Expat’ is the socially preferred term for someone who chooses to flee their homeland and pursue their fortune on foreign shores. Expats and migrants alike roam in search of streets paved with gold – but there’s a subtle difference.

When you arrived in Indonesia, chances are the red carpet was rolled out. You stayed in a top hotel while you organised your new home, car and domestic help. Your employer did what it could to ease your transition. Your family may even have visited to help you settle.

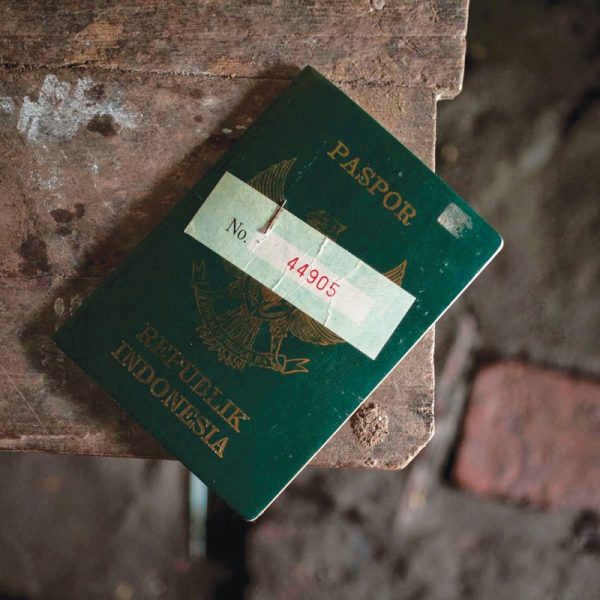

Consider the reverse journeys made by today’s Indonesian ‘expats’. The majority of them would not identify with the word – they were not met by the welcome wagon. Theirs is an altogether tougher existence.

Imagine sleeping on a hard floor, stomach empty, after yet another 21-hour work day, underpaid – if at all – and hundreds of miles from loved ones. These are the least of the complaints Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, an Indonesian migrant domestic worker formerly in Hong Kong, suffered at the hands of her employer. The worst were beatings with household objects until she could no longer walk.

PRIDE AND PRESIDENT

In February, Sulistyaningsih’s tormentor, Law Wan-tung, was found guilty of 18 of 20 charges, including grievous bodily harm. Perhaps it was this in part, which prompted President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo’s surprising comments on 14 February that Indonesia’s export of domestic workers is a matter of “pride and dignity” and should be altogether stopped. Jokowi asked the Manpower Ministry to create a clear, time and target-bound plan to halt the industry once and for all – a move supported by Nusron Wahid, the head of BNP2TKI (Badan Nasional Penempatan Dan Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja Indonesia, the National Body for Placement and Protection of Indonesian Workers). Further, according to Antara at the time, Jokowi found it “really shameful” discussing the matter in bilateral talks with Malaysia.

Strong words, Mr. President. Arguably, an honest day’s work is the polar opposite of ‘shameful’. It’s not the first time such views have been expressed, with the previous government’s decision to suspend migration to Saudi Arabia in 2011-2013, coming amid Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s similar sentiments.

But what does Jokowi propose as an alternative to the thousands of migrants seeking to go abroad every year? Does he have a handle on exactly how many people this impacts? And does he understand the root causes that drive them away in the first place?

THE NUMBERS GAME

Nobody actually knows for certain how many Indonesians are working abroad in foreign countries, legally or otherwise. Latest press estimates since Jokowi’s comments put the figure anywhere between 6.5 million (The Diplomat), to 4.2 million (Bloomberg), to the more conservative 2.3 million, of which over half are undocumented according to Jokowi as quoted in The Jakarta Post.

Up to six different bodies seem to be responsible for various slices of data on the subject: primarily the BNP2TKI itself, but also the Manpower and Transport Ministries. The problems with this are obvious: firstly, no clear laws bind these parties to share, compare – and, crucially – validate their data. Worse, the BNP2TKI’s official 2014 figures are a measly 10 percent of the latest estimate from the UN’s International Labour Organisation (4.3 million, 2009).

In destination countries, documented migrants may be recorded by embassies and manpower ministries, but again, cross-referencing this data to Indonesian sources does not happen, and even if it did, it would not account for the untold millions of illegal Indonesian migrants.

Perhaps then, administrative though it may be, Jokowi’s first move should be to task one body with the responsibility for coordinating accurate records of both documented and illegal migrants, and working with foreign governments and organisations like the ILO to properly understand the numbers.

DESIRABLE DESTINATIONS?

Assuming the percentages (if not the numbers) of Indonesian migrants in each destination country identified by the BNP2TKI are correct, 2014’s top five (Malaysia, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong and Singapore) account for 75% of all migrants.

First is Malaysia with 30%, where up to half of the estimated 2.3 million are undocumented. The draw across the Malacca Strait is obvious and age-old. But Malaysia’s pole position for Indonesian domestic workers is potentially in jeopardy. Not only are wages across the border lower than in rival countries – roughly Rp.2,500,000 per month versus almost double elsewhere – political tussling is affecting supply.

Since 2011, a memorandum of understanding between Malaysia and Indonesia fixing the total cost of hiring an Indonesian maid has bounced back and forth without proper enforcement. This allowed Indonesian agencies to charge higher fees, which desperate Malaysian employers accept. Recent reports suggest the memorandum has finally been signed, though its efficacy remains to be seen. Perhaps the cultural similarities that make Malaysia attractive to many may not be enough for our neighbour to hold on to the lion’s share of this market.

Taiwan’s higher wages will not be enough to ward off Jokowi’s plans to stop sending maids there. But wages of up to Rp.6,500,000 will be hard to replicate at home for unskilled workers. Hong Kong competes at a similar level and should benefit from regulations that require employers to pay the minimum wage, but reports of Indonesian maids accepting less than this until they ‘prove themselves’ abound, as do stories like Sulistyaningsih’s of underpayment. Singapore lags slightly behind, although in January the Indonesian Embassy there announced an increase in the minimum wage to around Rp.4,800,000. This is still considerably more than most domestic workers can earn at home: the official minimum wage in Jakarta is now Rp.2,700,000, but many maids here earn much less.

Saudi Arabia, with wages of up to Rp.4,000,000, was in first place in 2011 until President Yudhoyono’s ban, which lasted until 2013. To date, the two governments are still wrestling over agreements to protect both workers and employers, with the future of the market in the Gulf Kingdom remaining uncertain – tensions are certainly high. The Saudis’ propensity to execute Indonesian citizens on death row without proper forewarning (as on 14 April with Siti Zeinab Duhri, an Indonesian maid convicted of murder amidst uncertainty about her mental health) does not help.

ALTERNATIVES AT HOME

The reasons Indonesians choose to migrate abroad to work in a domestic capacity are clear. They believe they can provide a better life for themselves and their families back home. Indeed, remittances in 2013 amounted to Rp.88.6 trillion according to the BNP2TKI, a sum that increases year-on-year.

In the face of the figures, it is clear Jokowi has set himself a gargantuan economic task. How can local employment compete with the wages unskilled workers currently achieve abroad? This is surely the biggest question the President needs to address in his plan to halt export. But underneath the numbers – as with almost every issue in this country – lie social and political factors.

Indonesia needs to educate its educators in order to upskill its workforce and siphon the supply of domestic workers into higher-paid roles in different industries (provided these jobs are available). This unearths myriad, complex issues with the woefully inadequate education system, for one – another article in itself, in which the spectre of corruption would inevitably appear.

Meanwhile, as Indonesia moves towards middle-income stability, work can continue on the economic foundations needed to keep workers at home. There is no harm in the government working with host countries on improving the safety and protection of Indonesian migrant domestic workers – and indeed, as we have seen, there is already evidence of this in Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. But this, combined with higher wages, will surely only serve to make the migrant’s life even more attractive.

Therefore, it is really on the home front that Jokowi must do battle, if he wishes to save his countrymen from the ‘shame’ of domestic work internationally.

Until then, we can only hope today’s Indonesian migrants are safe, healthy and fairly compensated – and that if they are not, help is accessible. But as many of us know, in an expat’s life, there are no guarantees.