Tobacco companies in Indonesia could face challenging times, as regulators tighten. But with power and resources, cigarette firms have cause to be optimistic.

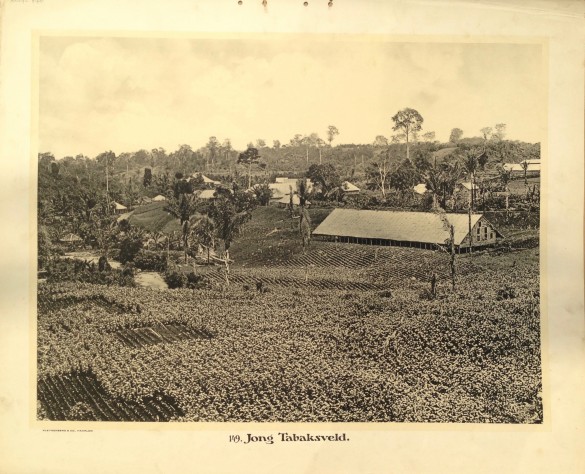

When it comes to the oldest businesses in Indonesia, farmers and plantation-related industries are among the first to ring the bell. Acknowledging the country’s fertile soil, Dutch colonials in Indonesia implemented new crop cultivation systems to gain revenue and fund operations at large in the archipelago. The likes of quinine, pepper, rubber, coffee, oil, and tobacco were among the chosen commodities to fuel the Dutch economic growth.

Although Dutch colonization in Indonesia has been over for quite some time, most of the commodities they cultivated still thrive today. Tobacco, however, could be facing stricter laws in the years to come, despite serving as a historical economic pillar in the country.

Introduced by Portuguese merchants in the 1600s, it wasn’t until 1863 that a Dutch businessman named Jacobus Nienhuys began building the nation’s tobacco sector. Tobacco brands began cropping up in the early 20th century, with the most famous one known as Bal Tiga (Three Balls). The brand came about following the invention of kretek. The cigarette made with a blend of tobacco, cloves, and other flavours was discovered by a man named Haji Jamhari, a native of Kudus in Central Java.

Jamhari, who suffered from chest pains, tried carrying out an experiment to reduce his pain by rubbing clove oil on himself. Believing the oil made him feel better, he aimed to achieve a deeper relief by smoking hand-rolled cigarettes after adding dried clove buds and rubber tree sap. His story spread quickly amongst his neighbours, and kretek soon became available in pharmacies. In those years, the substance was seen as more of a home-industry product. Cigarettes were hand-rolled, then wrapped in a dry corn husk without any branding or packaging.

After Jamhari made his revelation, the first mass production line of kretek was introduced by Nitisemito, a fellow Kudus local. He introduced cigarette papers in place of corn husks, created a brand name, and started doing promotional campaigns. Bal Tiga became popular and propelled the region’s economic growth for years to come. However, the competition was so fierce that Nitisemito eventually faced financial failure with the firm before he died in 1953.

Although Bal Tiga closed its doors, many tobacco brands that operated during the same period still managed to survive. Names like Sampoerna, Bentoel, Djarum, and Gudang Garam became the largest tobacco conglomerates in Indonesia. Witnessing the industry’s growth over the decades, international tobacco firms began eyeing the Indonesian market. In 2005, US-based Philip Morris International acquired Sampoerna. Four years later, UK-based British American Tobacco acquired Bentoel Group. As of 2014, there were more than 3,000 cigarette brands owned by 672 companies across the archipelago. This makes tobacco one of the most lucrative industries in the region, and a bona fide staple in the Indonesian economy.

As the fifth-largest producer of tobacco leaves in the world, cigarette prices are dirt cheap in Indonesia. With just US$1 smokers can buy their favourite pack of cigarette. Selling single-stick cigarettes is also common in the country, enabling the poor and even children to get their hands on tobacco. Mix this dynamic with a low excise tax and loose regulations, and the result is that one in every three people in Indonesia smoke. The country is now the second-largest smoking nation after China, and the fourth-largest in the world. It is even reported that Indonesian children, some as young as five years old, have taken up smoking.

These stats mean one thing for Indonesian tobacco companies: there is a large domestic market for the taking. However, it also means Indonesia’s tobacco control authorities have their work cut out for them.

During the New Order era (the period when Suharto was president), big tobacco firms profited greatly, and regulations remained laughable. After the regime collapsed at the turn of the century, the government implemented restrictions to address the nation’s tobacco epidemic.

Some of the policies identified tobacco as an addictive substance in the 2009 Health Law. The law also addressed cigarette advertising in the electronic media, the restrictions on tobacco sponsorships at sporting events and concerts, pictorial health warnings in cigarette ads and packaging, as well as smoke-free areas in public places. Anti-smoking groups emerged to remind the government to do its job and regulate the substance.

Today, Indonesia’s tobacco regulations are still considered weak by advocate groups and lobbyists. Although the tobacco tax increased this year, the government is also making a controversial move by finalizing the tobacco bill, which was initially rejected by the Health Ministry last December. Many speculate that tobacco companies are the brains behind the bill itself, and as such, it will only benefit the tobacco industry more in Indonesia.

In an interview with Indonesia Expat, Dr. Kartono Mohamad, a representative from the Tobacco Support Control Centre (TCSC) Indonesia, expressed disappointment with local regulations.

“Tobacco regulation in Indonesia is still weak, mainly due to naivety of politicians and decision makers on the magnitude of the dangers of smoking,” says Mohamad. “Society and government are still more fixated on the myths propagated by the tobacco industry rather than looking at the reality […] The seduction of money from the tobacco industry too [comes into play].”

With a long history of success, big tobacco names have strong political and economic resources in Jakarta. Tobacco tax has become one of the leading sources of Indonesia’s excise revenue.

This year, the country aims to pull in Rp.139.82 trillion (US$10.3 billion) from tobacco tax. Politically speaking, there is much speculation that big tobacco firms have strong connections to policy makers, and cash flows illegally into coffers in exchange for political favours.

In addition, big tobacco names routinely launch social programmes to build a good image in Indonesia. Some firms offer educational scholarships and sports-related scholarships to local youth societies. Many believe these efforts allow cigarette conglomerates to thrive, as regulations remain loose.

Though the myriad of anti-smoking groups seem to pose a threat in Jakarta, the tobacco industry has its own supporters. Alfa Gumilang, a representative of Komunitas Kretek (Kretek Community), tells Indonesia Expat, “We no longer need to add regulations that advocate against [the] tobacco industry because regulations that exist today are already quite a lot. There is no need for FCTC, [a] tobacco diversification plan, significant tax increases, prohibition of scholarships for smokers, [or a] health insurance ban for smokers, etc.”

With power and support – and so long as Indonesia is still among a few countries that have not signed the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) – big tobacco families remain optimistic about the Indonesian market.

As for regulations, Mohamad suggests the government should implement rules that will not harm tobacco farmers. In his eyes, laws can offer exemptions to farmers who might face economic hardship if the country makes moves to scale back tobacco production. There are also ways for tobacco farmers to shift their operations toward other commodities, he says, adding that those in charge could also be educated about not destroying the environment with farming activities.

Mohamad thinks tobacco leaf imports should be tightened up significantly, and that the government should pay more attention to educating the current tobacco labour force, guiding them towards a new line of work.

Gumilang offers his opinion on that matter: “If the government wants to create new regulations, it is time to create those which specifically provide protection for tobacco farmers, provide credit and technological assistance to them, and protect them from imported tobacco.”