Imagine a world without coffee! Even if you are not a coffee drinker, imagine the shopping centres and high streets without the ubiquitous coffeehouses, coffee shops, cafes and other outlets specializing in the sale of espresso, cappuccino, latte, café noir, mocha, café macchiato, or just java.

But several centuries ago, coffee was prohibited in quite a number of countries.

Even in the country of its origin, Ethiopia, coffee was banned by the country’s Orthodox Christians until 1889, as it was considered a Muslim drink. And on the grounds that it was an intoxicating drink, Muslim ulemas (scholars) in 1511, had done the same but overturned their decision some 30 years later. In Europe, King Charles II outlawed the coffeehouses in 1676 because of their association with rebellious political activists, but two days before the ban would take effect, he backed down due to the uproar that followed his decree. And for nationalistic and economic reasons, Frederick the Great banned it in Prussia to force people back to beer. Prussia, without any colonies where coffee was produced, had to import all its coffee at great expense. Luckily (my personal opinion) we have overcome these restrictions to enjoy the brew.

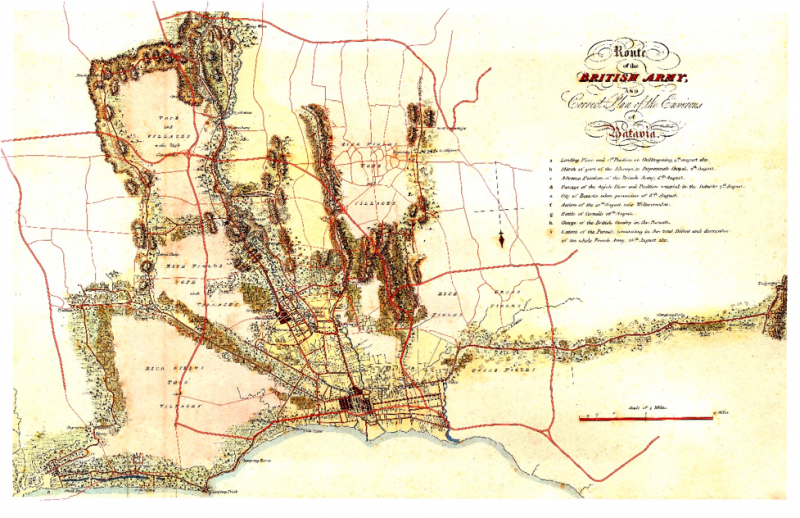

Originally from Kaffa, a kingdom in medieval Ethiopia, coffee (Coffea arabica) was brought to Arabia, to be more specific, to the present-day Yemen, where it was cultivated and exported through the port of Mocha. Starting in 1616 the Netherlands East India Company (VOC) bought their coffee there and took it to Batavia (present-day Jakarta). Coffee soon became a valuable and very profitable trade commodity, and in 1696 the first seedlings were brought to Batavia for planting in Java.

This first batch, planted on the estate of Governor-General Willem van Outshoorn, was shortly thereafter lost in a flood. The experiment was, however, repeated and in 1706, the first introductory sample of locally grown coffee could be exported to Amsterdam, together with one coffee plant. And, believe it or not, this seedling, nourished and multiplied in the Amsterdam Botanical Gardens (Hortus), became the grandparent-stock of the Arabica coffee plants in Brazil and the Caribbean. At least that is the story according to the Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch-Indië. Wikipedia tells a different story and credits the French with bringing coffee seedlings to Martinique, from where it spread to Mexico, Haiti and other Caribbean islands; while Brazil got its Santos coffee from the Isles de Bourbon (the present Réunion).

Around 1878, disaster struck, as in the coastal regions of Java the Arabica variety became susceptible to coffee leaf rust (Hemilea vastatrix) and had to be abandoned. When in about 1900 the Robusta variety (Coffea canephora), which was resistant to the disease, was imported from the Congo, the lower altitudes could be brought under cultivation again.

Before 1800, the VOC had imposed the growing of coffee on the population in the area around Batavia and in the mountainous region of West Java (Parahyangan). The district heads (Regent/Bupati) were contracted to each year deliver a certain amount of coffee beans. The VOC did not get involved in the cultivation, but the regents had to ensure that the population planted coffee, maintained the gardens and delivered the required amount of good quality coffee. During the second half of the 18th century, cultivation of coffee was extended into Central Java, but on a rather limited scale only. The main push into the rest of Java and the other islands was started by Governor-General Daendels (1808-1811) and subsequent administrators.

In the Batavia area coffee was most successfully grown in Rijswijk (now Duri Pulo, a short distance west of the Presidential Palace) and Meester Cornelis (some five miles south-east of the Palace, now Manggarai). The population apparently did not object to the forced cultivation. And the same applied to West Java, where the requested volumes and quality were delivered on time. In the other parts of Java and the outer islands—in particular western Sumatra and Maluku—the population was, however, less taken with the scheme of mandatory cultivation. The lure of additional income did, in the beginning, stimulate the population to grow coffee. In 1724, some one million pounds of coffee could be shipped to Amsterdam. But when carrot became whip, and the requested volume was increased to four million pounds (1727) and six million pounds in 1736, the people’s enthusiasm decreased considerably. The regents received six stuiver (five-cent piece) per pound, which had to cover purchase, and transport of the coffee to the VOC warehouse. The actual purchase (at farm gate) was done by the village heads. One can thus imagine that the price paid to the farmers was but a fraction of the one received by the regent.

Not only coffee was an enforced crop, but also sugar and indigo. This system of enforced cultivation, the Cultuurstelsel (Cultivation System), had been introduced in 1830 and forced farmers to grow export crops on 20 percent of their land, or alternatively provide 60 days per year of unpaid labour on public projects for the common good, instead of growing rice and other staple foods. At the same time, the collection of taxes was turned over to collecting agents, who were paid by commission. Unsurprisingly, the systems were widely abused: prices paid to the farmers were minimal, the weight of the purchased produce was tampered with, the 60 unpaid-labour days were often extended, or spent on private projects of the regional colonial officer or the regents. And the tax collectors ruthlessly squeezed the farmers dry to increase their commission. No wonder the system created widespread hunger and dissatisfaction.

The rise of a more liberal outlook and parliamentary questions about poverty and famine on Java, and the desire to allow private commercial interests to be involved in the production of export crops, led, in 1870, to the abolishment of the Cultuurstelsel. But because of its profitability, the cultivation of coffee remained enforced till the early 1900s.

Among the individuals who most passionately (and effectively) contributed to the rising liberal and self-questioning mood, was Eduard Douwes Dekker. A colonial civil servant since 1838, he was in 1857 appointed Assistant-Resident in Lebak, western Java, where he started to openly protest about the exploitation and maltreatment of the natives by the regents, and the misconduct of the colonial authorities.

He resigned before he was dismissed and returned to the Netherlands. There he continued his protestations in newspaper articles, pamphlets and in 1860 published his book Max Havelaar; or, The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company, under the penname Multatuli.

Deprecated and discredited by his superiors in the colonial administration, he is now listed as a hero in the Indonesian annals for the period of the Dutch East-Indies, 1800-1945—together with prince Diponegoro, the initiator and commander of the Diponegoro war against the Dutch in Jogjakarta / Central Java, and Teuku Umar, the guerrilla leader in Aceh.

The coffee cultivation on Java and elsewhere in the archipelago was, fortunately, not brought to an end by the mismanagement and misconduct of the colonial administrators. Production in 2012-13 of coffee in Indonesia was some 12.7 million 60-kg bags, of which nearly 11 million bags were exported.