The Lombok Strait averages about a thousand metres in depth, though in places it is far deeper. And not only is the strait deep, it is treacherous. Its southern entrance is guarded by Nusa Penida and Lombok’s Bangko-Bangko, where the Japanese positioned their big guns in the Second World War.

Today’s surfers pit themselves against the big waves of Desert Point, described as one of the longest breaks on the planet and an ‘evil place’. Between the two points a sill reduces the depth to around 200 metres, creating racing currents and dramatic conditions, as the warm waters of the Pacific rush through to join the cooler Indian Ocean in the South.

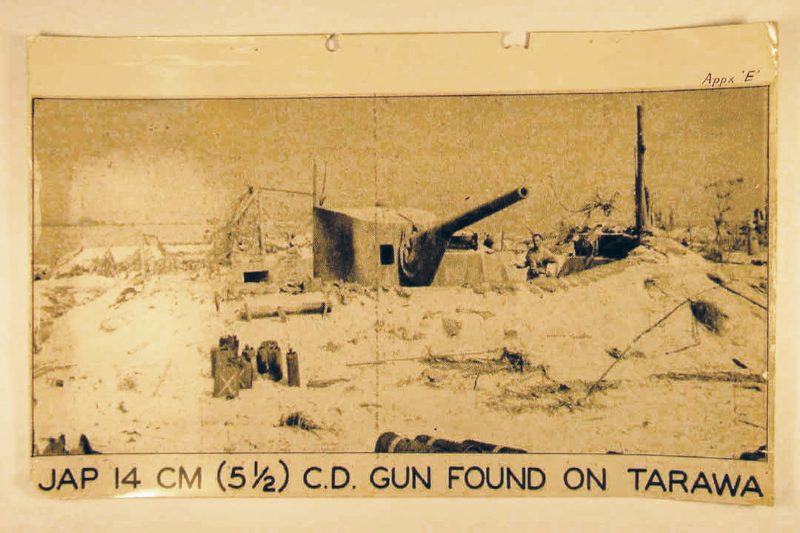

The Lombok Strait is the only deep water passage from the Indian Ocean to the Java Sea in this part of Indonesia, and was of great strategic importance in the Second World War. Most underwater passages by US, British, Dutch and Australian submarines from the big base at Fremantle were made through it. The fast and turbulent currents sometimes forced these submarines to surface. The Japanese navy knew this, and patrolled the channel. Their three six-inch guns, manufactured in Germany were positioned at Bangko-Bangko (also known as Cape Pandanan), where they could pick off sea traffic as it negotiated the treacherous passage. Similar gun placements on Gili Trawangan and Bali enabled the Japanese to triangulate their defence of the channel.

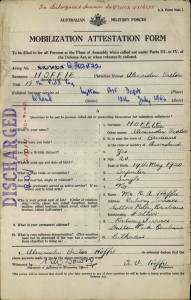

In the final months of the war, a band of four young men – Australian and British Z-Force commandos – went behind enemy lines to reconnoitre the south of Lombok: Lawrie Black, Alex Hoffie, Malcolm Gillies and James Crofton-Moss. Four went and two returned. An air operation had attempted to destroy the guns. Their mission, code-named Starfish, was to determine the condition of the guns, to gather intelligence on enemy defences, and if necessary to lay the ground for a demolition team which would follow to destroy the guns. In March 1945, the men travelled from Australia to Lombok on the Rook, a US submarine. Tensions and youthful spirits were high when a fight broke out between the Australian commandos and the American seamen in the confined space aboard. The stoush apparently involved a lot a talcum-powder and ended with a few bruises, a little blood and sore heads – but no disciplinary action.

The team was dropped south of Cape Sara, near the beautiful Selong Belanak Beach. While the submarine waited in the dark, the Australians floundered across the reef and made it ashore to the east of the point in a rubber dinghy, getting thoroughly swamped in the surf along the way. Stores were buried in pig holes, where reportedly the Japanese did not find them, though it transpired that the local Sasaks were well aware of the cache. The team returned to the submarine. After a second landing at Pengantap Bay, to the West of the first landing, more stores, the rubber dinghy, outboard motor and fuel were stowed in a sea-cliff cave. The team set off to explore the area, finding water and making camp before heading inland and north-west towards the gun emplacements.

The four men spent around six weeks on the island, managing to make friendly contact with the locals, with whom they met frequently, exchanging propaganda leaflets and cash for information and fresh supplies in the form of chickens, eggs and vegetables. A substantial amount of information was gathered and later reported back to Command in Darwin. After around three weeks, they moved camp to Batugendang Point, just south of the gun placements at Pandanan Point. A replacement radio was requested after the power pack for the first set burned out: it was duly delivered with more stores in a night-time airdrop in the bay below the new camp.

About a month after they first arrived, the party divided, Black and Hoffie heading off with some locals on a recce, while Gillies and Crofton-Moss returned to the first camp to collect stores and report home by radio. The two became separated, getting bushed in the thick scrub. James Crofton-Moss never saw his friends again. The remaining three managed to avoid the Japanese until the end, when they were finally discovered. They were sitting around their camp in the early morning, cleaning up their breakfast dishes, when a snapped twig alerted one of the men.

The alarm was raised, there was a clatter of dropped dixie bowls and, as the three ducked, grabbed for their weapons and ran off into the bush, a storm of gunfire followed them.

Malcolm Gillies was wounded and captured. The remaining two, Black and Hoffie, made it out a few days later, having found their way back to the first camp and south to the coast. After several attempts, they made radio contact with the base in Darwin. Recovering the rubber dinghy from the cave, they rendezvoused with a Catalina seaplane offshore, and were safely returned to Darwin.

Alex Hoffie died fifty years later in 1996, Lawrie Black in 2009. Malcolm Gillies and James Crofton-Moss lie in the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Ambon. Both were captured and beheaded by the Japanese. The remains of the Japanese guns can still be found, covered in tropical vines and rusting away on the ridge at Bangko-Bangko. The guns are very difficult to locate, so overgrown that a machete is required to cut away the weeds. The headland is thickly covered with low, dense and thorny scrub; little wonder that Crofton-Moss and Gillies became disoriented.

Alex Hoffie died fifty years later in 1996, Lawrie Black in 2009. Malcolm Gillies and James Crofton-Moss lie in the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Ambon. Both were captured and beheaded by the Japanese. The remains of the Japanese guns can still be found, covered in tropical vines and rusting away on the ridge at Bangko-Bangko. The guns are very difficult to locate, so overgrown that a machete is required to cut away the weeds. The headland is thickly covered with low, dense and thorny scrub; little wonder that Crofton-Moss and Gillies became disoriented.

A studio portrait of Gillies in uniform can be found on the Special Forces ‘Roll of Honour’ website. The pensive looking young man stares off to the right of the frame. One wonders what he endured during the month between his capture and execution. Tales of derring-do, night-time escapades in rubber dinghies and talcum-powder battles pales somewhat when you look into the eyes, as it were, of this young man.

It was only three months later that the Americans dropped their bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the war and the lives of one-hundred-and-twenty-nine-thousand Japanese citizens. Lest we forget…

—

This story is an excerpt from Mark’s new book, a work in progress. Tentatively titled The Glass Islands, the book will be available in 2016 and will feature more of Mark’s unique style, weaving tales of travel in eastern Indonesia with anecdotes and personal reflections on the people, cultures, politics, history, environment and myths of the region. He can be contacted at [email protected]