Nearly all UN members have endorsed the 1961, 1971 and 1988 conventions on the prohibition of the main illegal recreational drugs. The objective of these mandates was, in the words of William Brownfield, US Assistant Secretary of State for Drugs, to “reduce the misuse and abuse of harmful products throughout the world.” And the way to reach this goal was to launch an all-out war against drugs. Now, half a century later, the belief that stamping out drugs is not the best way to manage the problem is beginning to take hold.

We are talking here about cannabis, the world’s illicit drug of choice. In the USA, four states have legalised it, as has Washington, D.C., while most European countries have decriminalised its use – but not drug-dealing. Uruguay is the first country to have legalised the whole chain, from growing to distribution and the consumption of cannabis.

In respect of other drugs (and there are quite a number of them) the legislation in Western countries is not as lenient, yet. Users of cocaine and crystal methamphetamine are sometimes still prosecuted, and heroin users might be jailed, but at the same time are provided with access to clean needles and methadone; a substitute to stop addicts from overdosing. In Amsterdam the policy goes one step further. Heroin addicts who can prove that they have tried to kick the habit several times, but failed, can get heroin to smoke or inject three times per day at a municipal health centre. The result is that addicts have disappeared from the streets, and those under 40 years of age are almost non-existent.

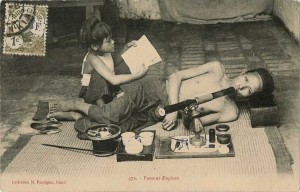

100 years ago in the Netherlands East-Indies, the main narcotic was opium. Used for either medical or recreational purposes, the substance was completely controlled by the colonial authorities through its 1893 legislation called the Opium Regie, or Opium Monopoly. Raw Indian opium was bought through an agent at the Calcutta auction with the British Government guaranteeing the quality of the product. This outsourcing was adopted as the cultivation of poppies was forbidden, for reason that in the wide expanse of the archipelago it was nearly impossible to control production. Moreover, it was questioned whether local cultivation would yield a product of reliable quality. The Government was thus the sole, monopolistic importer and processor of the raw opium, taking care of packaging and shipping for resale by leaseholders, too.

Like elsewhere in the world, the 19th century was fairly tolerant of opium smoking; it was not perceived as a menace to health and society. In 1884 a Royal Commission in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, questioned a girl of good family and education why she smoked opium. Her answer was: Why do people commence to drink? Trouble, I suppose led me to smoke. I think it is better than drink. People who smoke opium do not kick up rows; they injure no one but themselves, and I do not think they injure themselves very much.

Back in the Netherlands East-Indies, research in the mental hospital at Lawang could not find any connection between mental illness, or heredity, and the smoking of opium. And experts opined that moderate use of opium did little harm to Asians. The Lawang researchers reported that: …the typical representation of the damages of opium are highly exaggerated.

The writers cite examples of coolies who took a certain amount of opium on a daily basis and were still able to perform heavy physical tasks. Singapore’s coal harbour coolies, for instance, reached old age and were known as strong and industrious workers even though they smoked 10 to 20 times more opium than Javanese labourers.

I don’t know whether the writers were enlightened freethinkers and much ahead of their time, or trying to justify their own habits, but their statements are certainly different from what one would expect to read in a 100-year-old encyclopaedia. However, the article also contains statements and references to studies that oppose the above opinions. The authors themselves, for instance, mention that unrestrained smoking [of opium] will eventually ravage the body. But that of course refers to unrestrained smoking, rather than taking a certain amount of opium.

The Opium Regie was tweaked and adjusted frequently as the Government faced the difficulty of predicting how much to import and distribute to the various lessees and opium den operators. If too little was bought in Calcutta, the lessees – assisted and supported by large powerful groups with commercial interests in the trade – would smuggle the quantities needed to offset the shortage into the country. And when too much was distributed, the lessees would (illegally) enlarge the sales area assigned to them.

In the 20th century, the drive to eradicate opium-smoking gradually got stronger, and various methods to reach this objective were used. The number of regions where opium was allowed to be sold was reduced, as was the number of opium dens. In Java and Madura, for instance, the number of dens was reduced by 20 percent, or from 1,025 on 1 January 1905 to 823 12 years later. Great care was taken not to decrease their number too fast as this would undoubtedly lead to smuggling and illegal sales.

The dilemma the Government faced was immense. On the one hand the desire to curb opium-smoking was genuine. However, the revenue collected from opium was highly profitable. In 1916 revenue stood at 35,345,160 guilders, with operating costs (including raw materials, processing, packaging, shipping, cost of preventing smuggling, and pensions) at 6,933,646 guilders only, thus leaving a net profit of 28,411,514 guilders – the equivalent of about US$350,000,000 today.

It was the Second World War that brought an end to the Opium Regie and the profits.

It appears that the main reason for the lack of success of the anti-opium-smoking campaign was the profits derived from selling opium. Hence l’histoire se répète, as nowadays the big profits are still the main reasons that the war on drugs has been a failure. Only now, the profits are made illegally by large, well-organised criminal outfits who have the capital to easily buy their way around obstacles.

The ones getting caught (and executed) are typically the small-fry, the little mules, or at best some low-level organisers.

The heads of the large powerful groups with commercial interest in the trade are sitting back and enjoying their illicit profits.

An English language publication recently published an interesting Editorial Corruption Weakens Jokowi’s War on Drugs, in which it is stated that the core problem of Indonesia’s war on drugs is “…the corrupt officials, rotten penitentiary system and of course the judiciary system as a whole rather than just foreigners smuggling drugs into the country.”

It’s high time to try an alternative approach to curbing drug-use. Legalising drugs would knock the bottom out of the market and eliminate the immense profits. It would also eliminate the need for kick-backs and other corrupt practices. Rehabilitation of drug users, together with a clean-needle programme, rather than jailing, would also be a positive first step.

That, however, seems to be a distant dream as the new anti-drugs czar, Comr. Gen. Budi Waseso, wants to stop the rehabilitation services for drug users provided by his office (National Narcotics Agency, BNN). He also opined that, similar to the policy regarding illegal fishing in Indonesian waters, boats used for drug smuggling should be sunk, but with their crew!