Indonesia has held its ranking at 47 in the world talent competitiveness index, making it the lowest ranked Southeast Asian country when it comes to developing, attracting and retaining talent in the country.

The rankings, compiled by Swiss business school IMD through its World Competitiveness Center, are based on both historical data as well as surveys with thousands of executives from 63 economies, based on three categories of indicators namely investment and development, appeal and readiness.

The index ranked Indonesia 47 as per the previous year, below neighbours Singapore (13), Malaysia (28), Thailand (42) and the Philippines which managed to leapfrog over Indonesia to 45, up ten spots from last year.

Despite managing to retain the same spot as last year, Indonesia sees a decline in the scores of all three of its indicators. For investment and development, IMD ranked Indonesia at 56 after scoring notably low in public expenditure on education, pupil teacher ratio and female labor force. The most encouraging score it received in this category was for employee training, for which it was ranked 19 in the world.

The readiness category, which assesses an economy’s ability to nurture skills among its populace that match those needed by its economy, includes an acknowledgement towards Indonesia’s impressive labor force growth. However, it scored badly in almost all other indicators, particularly student mobility inbound and educational assessment.

Out of the three indicators, Indonesia’s strength lies in its appeal factor, which considerably boosted by its favorable personal income tax rate, which is ranked at 4.

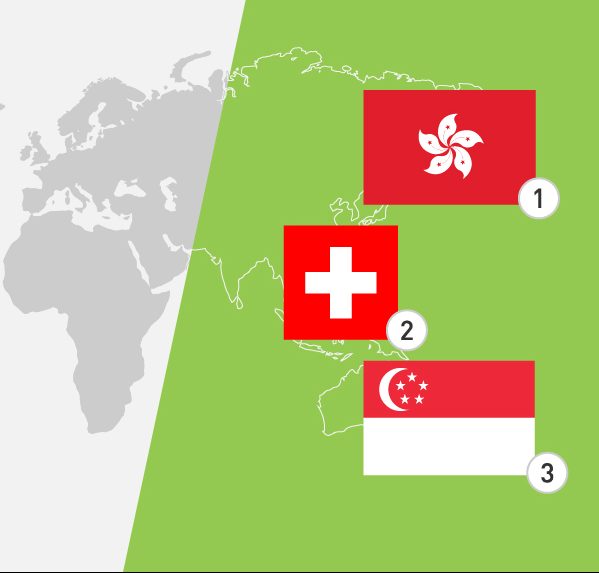

The top three spot in the ranking is occupied by Switzerland; and according to Dr Arturo Bris, the director of the IMD World Competitiveness Center, has a “perfect combination” of developing local talents and attracting foreign ones.

“The education system is extremely focused on readying people for what the economy needs – technical education and innovative skills. But for other jobs such as dentists, nurses and services professionals, they open up their borders to foreign talent,” Dr Bris said, as quoted by The Straits Times.

The key to having competitive talent, he explained, is having the right government policies to support the development of talent in the country.

“The problem is when policies become inconsistent with the country’s talent management model,” he said. “If the government shifts its immigration policies in response to pressure from the local population, it will also need to shift towards more investment in public education,” he said.