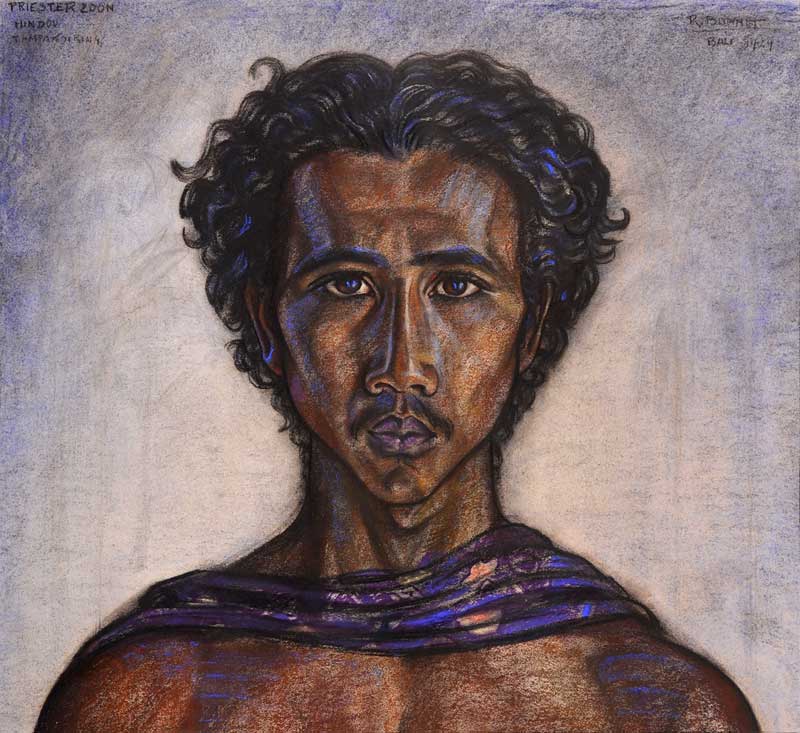

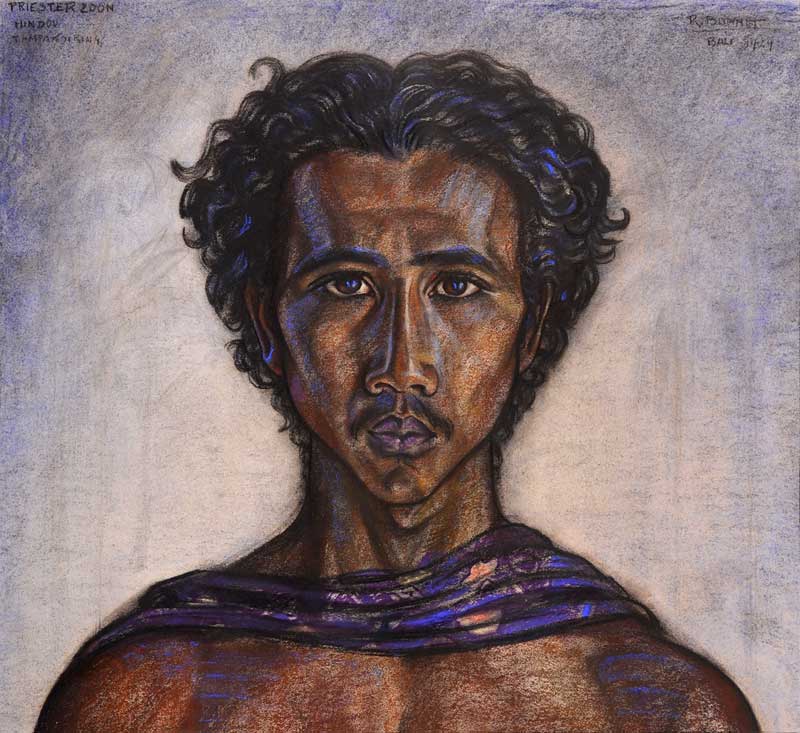

There is no attempt to sweeten or idealize the subject. This boldness is a direct carry over from Bonnet’s highly praised portraits of Italian peasants made before his arrival in Bali. The boy has a noble, self-assured demeanor but he is no classic beauty. Using dark angular outlines and dramatic shadows, Bonnet added an element of stylization often seen in European modern art during the first half of the 20th century. Nonetheless the boy remains a real breathing person, somebody we could meet on any street corner even today.

As many artists of his era Bonnet embraced the major principle of the Arts and Crafts Movement that all art was inspired by nature. So, too, he bemoaned the damaging effects of the Industrial Revolution. Bonnet sought refuge in Anticoli Corrado, Italy and artists’ village northwest of Rome. There he searched for inspiration in nature and the roots of western art. His two biggest influences were Renaissance drawings and frescoes. Eventually even the remote artists’ village proved too close to the beast as Bonnet sought an even more pristine environment free of modern influence. Bali was brought to his attention by W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp, another Dutch artist living in Italy, who had first visited the island in 1904 and written several books about it. Taking his advice Bonnet sailed to the Dutch East Indies in search of his muse and destiny.

Like his more famous predecessor, the gay German artist Walter Spies, Bonnet decided it was wiser to live in the village of Ubud, a safe distance from the watchful eyes of the Dutch colonial regime, which outside a few enlightened beings was hopelessly reactionary as far as politics and social issues were concerned. Both Spies and Bonnet were guests of Cokorda Gede Raka Sukawati, a prominent member of the colonial parliament, who understood that enlisting these two men could help realize his desire to make Ubud an important cultural destination.

While the question of what relationship Bonnet had with the anonymous son of the priest is irrelevant as far as the artistic merit of the work is concerned, it is nonetheless a potentially intriguing anecdote that gives greater insight into who Bonnet was and the time he lived in. Bonnet was 34 years old, not a boy but not old, and Bali represented a magical world where dreams could come true. Unlike the flamboyant Spies, who made little secret of his sexual bias, Bonnet was reserved even formal. Although his best friend Willem Hofker realized Bonnet was gay, they never mentioned the subject in a “don’t ask, don’t tell” arrangement. Unlike Spies, there are no tales of Bonnet cavorting with underage men, a habit that would earn Spies a jail sentence in spite of his many friends and connections.

Portraits in which the sitter stares directly at the viewer are rare because they are inherently provocative. When a stranger stares you in the eye most people avert their faces rather than acknowledge the person because the act raises questions about the relationship between the subject and the viewer. The act can be both an invitation for dialogue or confrontation. It is akin to what we experience when we get caught staring at a stranger in public – voyeur! Of course we especially do this when there is something remarkable – great beauty or oddness that attracts or repels or both! In Bonnet has left the work as a true living experience. The artist is long gone but the boy lives on. Bonnet was not a shallow man. He understood this.

In colonial times a native staring directly into the eyes of a westerner was strictly taboo! In the first half of the 19th century a British military officer who visited Bali wrote an article for a Singapore colonial rag announcing his outrage at the audacity of Balinese natives who would dare walk up to him with curiosity and stare straight into his eyes! In the British colonies such a surly chap would have surely been whipped.

This was not true of everyone. Beginning with Sir Stamford Raffles a growing number of officials and interested parties began to realize that the Balinese sense of independence and pride was a good thing. At one point some even proposed that Islam had effectively placed a debilitating film over the eyes and minds of the far more docile Javanese who stared politely down when spoken to by a superior. Of course such suppositions are gravely flawed because the strict hierarchy of Javanese society and often excruciating etiquette can be traced back to the puissant Hindu-Buddhist Empires of Medieval Java. Bali is also by no means a universally egalitarian society.

The artwork also belongs to the tradition of Thomas Hart Benton and Diego Rivera who sought to immortalize the natural nobility and pathos of peasants and the working class. It was an international movement. Bonnet would go on to create large fresco-like oils glorifying Balinese peasants. While his politics are unknown, what we do know is that he loved the Balinese and always strove to promote and protect them as best he could for more than 40 years. Indeed in comparison to Spies, who has been portrayed time and time again as a Great Lion of Bali, Bonnet has been accused of being dry and pedantic. Yet if one weighs their respective work and accomplishments the long term impact of Bonnet – the Puri Lukisan alone has proven far more enduring than the fabled glamour of his friend.

Perhaps the greatest insult of all is Bonnet’s depiction as the main protagonist in Nigel Barley’s tawdry historical novel Island of Demons. Aside from being riddled with all manner of errors, Barley has seen fit to portray Bonnet as some sort of gay Dutch hippie who after being seduced by Spies to a night of romance comes to the realization that this was a one time blessing. For the rest of the novel Bonnet pines for Spies’ enduring love with comedic-tragic results. Of course Mr. Barley is channelling his own homo-erotic fantasies but his liberty in portraying Bonnet is an utter travesty that borders on libel. Spies and Bonnet were never lovers and were not even remotely attracted to each other.

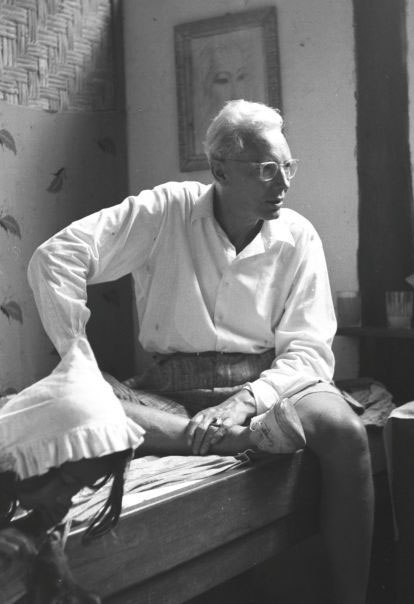

Dubbed a “Sunday’s Child” by his family, a reference to someone with a special sensitivity for art and beauty, Bonnet’s life was varied between elation and tragedy especially as he grew older. In 1938, like Spies, he was under investigation for homosexual activities. During the Second World War he was sent to a terrible Japanese prisoner of war camp and nearly died of illness and starvation. After release he was unable to return to his beloved Bali, which was gripped with violence and revolutionary fervour. When he did many of his old friends had died or fled the new order. Now hitting middle age his physical condition was vulnerable because of the camp and enduring hardship – hunger, dysentery, malaria, parasites, all manner of infections and moulds!

Once again at 62 he was forced to leave Bali for political reasons in 1957 just after he repeated this third refusal to sell a large oil painting to President Sukarno. His return to Holland was equally bleak. The art scene had changed forever. A new generation of young modern artists denounced him as an anachronism. As the nation rebuilt its shattered economy and shed its colonial legacy, few people were interested in Balinese culture.

In the end it was the Balinese themselves who honoured him for his many accomplishments. Passing away in 1978 almost the same time as his old friend Prince Cokorda, his end, however, was glorious. His ashes were returned to Bali and cremated with those of Cokorda Sukawati of Ubud in 1979. As for the priest’s son – no further information is yet available.