In more simple times, the old adage “Possession is 90% of the Law” was the rule. If you owned the work of art, you also owned the copyright. While this meant little for the vast majority of art, collectors and institutions that owned Iconic Images like the “Mona Lisa” or van Gogh’s “Starry Night” often reaped enormous sums of money by selling the reproduction rights.

As brilliantly illustrated in the Robert Hughes’ television series “The Mona Lisa Curse”, huge profits made by a new breed of speculator-collectors on works of art they bought for a pittance from struggling artists provoked cries of foul play led by major artists such as Robert Rauschenberg. He demanded that the artist-creator also receive a share of the windfall profits gained from their intellectual property.

While some countries, like Holland, enacted new laws that stipulated that living artists receive a percentage of subsequent sales of their works, for the most part the old ways continued unchanged. There is one exception in regard to intellectual property right as many countries passed laws saying that unless a work of art was sold by the artist with a contract stating that he had sold both the art piece and the copyright, then the copyright remained with the artist. These laws were largely based on those governing the copyrights of authors and their heirs which, unless specifically contractually stated, extended until 50 years after the death of the writer. A similar law exists in Indonesia.

While noble in intention, like many laws, few artists ever benefit from their rightful copyright simply because outside of a handful of better known works by better known artists, there is almost no demand. Ironically artists are often overjoyed to have their work reproduced in the media for absolutely nothing because it is a form of promotion. Further even if they decided to pursue their rights, the legal costs, and time involved, are so prohibitive that it would become a futile exercise.

The pre-World War Two modernist painters and sculptors are a good illustration of this phenomenon. Produced for the foreign market, the vast majority of these remarkably original works of art were exported long ago. While the Pita Maha artists association regulated both the quality of the work and transparently sought to guarantee that they were not only sold for a fair price, but also that the majority of the sum paid ended up in the pockets of the artist, in many cases the artists received little for their art, much less their original ideas. So, too, the prices of these remarkably works of art rose incredibly in the last years and have been the subject of numerous books. Copyright was certainly not paid and it is even doubtful if the heirs even received a copy of the publications.

National Governments, including Indonesia, have also claimed the rights of reproduction of iconic artworks such as Borobudur’s Buddhas and Prajnaparamita, the Buddhist Goddess of Supreme Wisdom, which has appeared on the covers of numerous books. Again, while these ideas are noble and well intentioned the results are often messy and counterproductive because serious publications honouring great art and artists are an important element in keeping their legacy alive.

For example, although I authored a major book on the art and life of the Dutch artist, Willem Hofker, who can be described as one of the most poignant of the expatriate artists who lived and worked on the island before the Second World War, copyright has been used to prevent my publishing a new edition incorporating extensive new information I have gathered in the last decade.

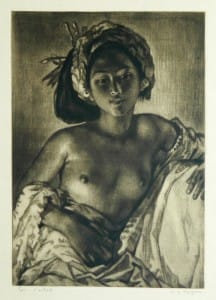

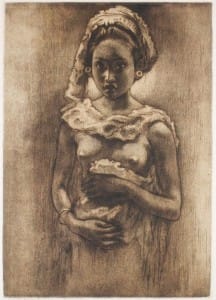

The problem is that the family was not pleased with the information I included, concerning his relationships with his models in an essay published on Hofker in the 2009 catalogue of Bali’s Pasifika Museum. I had learned years ago when I interviewed Gusti Mawar, one of his most beautiful models, of his love of Balinese women, and in this case their torrid affair, which certainly helps explains the heavy current of eroticism in his paintings of her.

As a result, the family decided to exclude me from a forthcoming book on Hofker that will not only be sanitized and censored, but also authored by a self-important newcomer Gianni Orsini, who has never spent much time in Bali or Indonesia and nevertheless presents himself as a major expert on the field. Notably he never met Maria Hofker or any other of the major players of the time. His long-winded digressions recently published in two Christies’ catalogues are predictably full of speculative fluff, effusively romantic odes to Bali and very little content since his knowledge is limited at best. My attempt to produce a book based on more than 20 years of research in Bali and Holland has been prevented by their using control of the copyright to prevent any other publication. I guess it does not matter since few, if any, ever read the texts anyway!