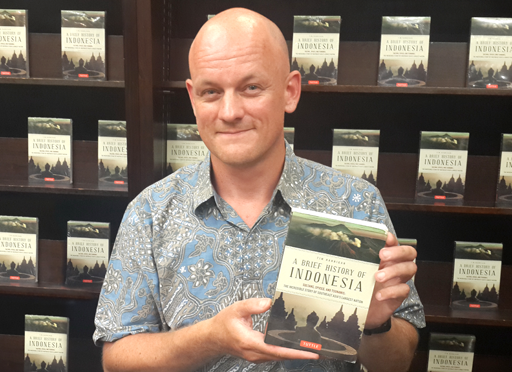

A Brief History of Indonesia by Tim Hannigan

pub. Tuttle 2015

pp.288

ISBN 978-0-8048-4476-5 (pbk)

ISBN 978-0-4629-1716-7(ebook)

The sub-title is far from the brief: Sultans, Spices and Tsunamis – The Incredible Story of Southeast Asia’s Largest Nation.

When Tim Hannigan first arrived in Indonesia “as an earnest young backpacker with a passion for history“, he was unable to find anything with a general overview; just academic tomes and guides to tourist ‘obyeks’ of interest. These guides, phrase books and beautiful coffee table books portraying landscapes, flora and fauna, and meals, are still the main stock of non-fiction reading to be found on the shelves of bookstores situated in malls and airport departure lounges.

But now Periplus stocks two paperback volumes of narrative history, both by Tim: Raffles and the British Invasion of Java, and now this one, the result of far less intensive scholarship, albeit with an extensive bibliography and index.

This book is less concerned with dates than with context. In our interconnected and interdependent world, the importance of what is now known as the Indonesian archipelago in the shaping of the world geopolitical map we know today is barely recognised by Indonesians themselves, let alone visitors.

The archipelago was formed as Asian and Australian land masses separated, so its early history was determined by geology and is unwritten except by archaeologists. Climate changes lead to migrations of early hominids; a great Ice Age had lowered sea levels, and what is now a nation was land-linked to Asia and sea journeys were shorter. The Java Man dates back some million years, and the recently discovered metre high Homo florensiensis in Flores proved that sea journeys were made at least 100,000 years ago.

The ‘Hobbits’ were followed much later by the Melanesians, who still predominate in the easternmost regions of the archipelago. Then some 7,000 years ago the Austronesians, “the greatest tribe of maritime travellers the world has ever known“, set forth from “the damp interior of southern China“. It took a further two and a half millennia for them to reach Sulawesi, and that’s when Indonesia’s history began: c.2,500BC.??There are no barriers to trade along the coastlines between the Red Sea and Africa in the westerly direction and to Japan and China in the other. The seasonal monsoon winds provided easy sailing through the Malacca Strait. During the equatorial dry season (summer), the winds carried ships with their cargoes to the north-west and to the north-east during the wet season (winter).

Lying midway along the trade route there was the incentive for traders to settle. Here it must be noted that until 1867 when the Straits Settlements on the Malay Peninsula were declared a British crown colony, their affairs were intertwined with those of South Sumatra and West Java in terms of trading and piracy.

The volcanic activity and tropical climate provided the fertility suitable for agricultural settlements, particularly in Java. As well as goods to sell or barter, traders brought their religions – Hinduism and Buddhism, and later Islam – and languages. These traders also sought the riches found here: tin from Palembang in South Sumatra which also provided pepper, and the spices, nutmeg and cloves, from the far Moluccas.

Before then, there were “Empires of Imagination”: Here and there some pretender prince, with ideas too big for the traditional role of the village chief, might have seized control of a federation of hamlets or a growing port. Once he had done so he would have found himself in need of a political concept to bolster his new position as head of a proto-state. The Indian idea of kingship was perfect for the task. Situated at the junction of the sea lanes in South Sumatra, from the 7th to 12th centuries the Buddhist trading ‘empire’ of Srivijaya (aka Sriwijaya) was able to dominate the surrounding states, including those across the Straits of Malaka. By the time its influence had waned some six centuries later, kingdoms in Java had already sought permanence through the construction of stone temples, such as the earliest on the Dieng plateau which was built by Shiva worshippers.

The Sailendra Dynasty in central Java, a trading rather than a maritime kingdom, possibly had ties with Srivijaya because of the religious connection, Mahayana Buddhism, as portrayed in their monument Borobudur, built during the 8th and 9th centuries. They were supplanted by the Sanyaya dynasty who took Shiva, the Hindu god as their key deity and erected Prambanan Temple and lots of smaller temples in the surrounding countryside.

In East Java, at the end of the 13th century, the Mongols, who were then ruling China, sent a number of fleets to extract tribute from the traders. In 1293, the final one was repelled by Raden Wijaya, who had invited them in the first place. He then “went back to his little village … and turned it into an empire called Majapahit. … Later Javanese kings, nineteenth-century European orientalists and strident Indonesian nationalists have all retooled its reputation to fit their own prejudices and purposes.”

The introduction of Islam is less well documented. By the early thirteenth century, there would almost certainly have been Muslim communities living in ports around the Straits of Malaka. Hannigan suggests that the creeping conversion could well have been a matter of “kingly pragmatism”, the need to work with the increasing number Muslim traders passing through or settled with local wives; the first converts.

It is in relatively recent times, the past 400 plus years that European powers – the Dutch, English, Portuguese, Spanish and French – named the “Spice Invaders” by Hannigan, came in search of the source and tried with varying success to monopolise the trade. However, events ‘back home’ was to lead to what is now an independent Indonesia. The storming of the Bastille in 1789 and the start of the French Revolution lead in political and economic terms to what has been termed the ‘Age of Enlightenment’.

Out of this came the idea of European intellectual and moral superiority and the spurious moral imperative – the idea that “we know what’s best for them” and the contemptuous notions of the ‘ignorant native’ and the ‘Asiatic despot’. One may surmise that the ‘inferiority complex’ engendered remains in the national psyche, and is the fundamental reason for the current rise in nationalism.

Sukarno once said: “Never forget your history.” To which I would add “especially that not written by the ‘winners’.” At the book launch in Jakarta, I suggested that this ‘Brief History’ be translated into Indonesian as an all-purpose supplement to the shallow versions of national history ‘approved’ by successive governments.

Tim Hannigan’s Raffles book has recently been translated into Indonesian and is available in Gramedia.