There are countless horror stories of expats who invested in property and started businesses in Indonesia only to lose everything. Some naively trusted an unscrupulous real estate agent or lawyer or business partner, many had a vengeful spouse take everything after a marriage breakup, and others were chased out of town by business rivals.

Local media recently reported the case of a British man who in 2005 spent over $3 million to buy 2.86 hectares of an area north of Kuta in Bali to be developed into 40 luxury villas that he was told would sell for $1 million each. Nick Hyam claims he was swindled by local lawyer Rizaldy Watruty and Canadian expat Gina Machura, who were involved in the deal, because the property was overvalued and he never received any land title deeds. But Denpasar District Court this month cleared the two of embezzlement and fraud charges. Hardly surprising.

A foreign individual cannot directly own land in Indonesia. Period. Anyone who says otherwise is selling something or doesn’t know what they’re talking about. The 1960 Agrarian Law states that Indonesia’s land is a “gift from God” to the Indonesian people and the nature of this relationship is eternal. The land is a “national treasure” to be controlled by the state for the maximum prosperity of the people.

At best, foreigners can invest in property through several means, most safely by forming a foreign investment company (PMA), which can own titles to build on or utilize land for decades. Alternatively, the PMA can be used as a legal entity through which nominee agreements can be made. Under this method, a foreigner can nominate a “trusted” Indonesian citizen or company to buy freehold land for them. This is extremely risky, especially if the foreigner does not have a PMA, as without it they have no means of legal recourse in the event of a dispute.

When property disputes go to court, the judiciary is notorious for handing down verdicts to the highest bidder. Foreigners rarely win and if they stay and fight, their opponent may find a way to have them deported on trumped up charges. Just because you possess “right to use” documents for a property, the judge presiding over your case may not necessarily know the law, let alone care to uphold it unless there’s something in it for him.

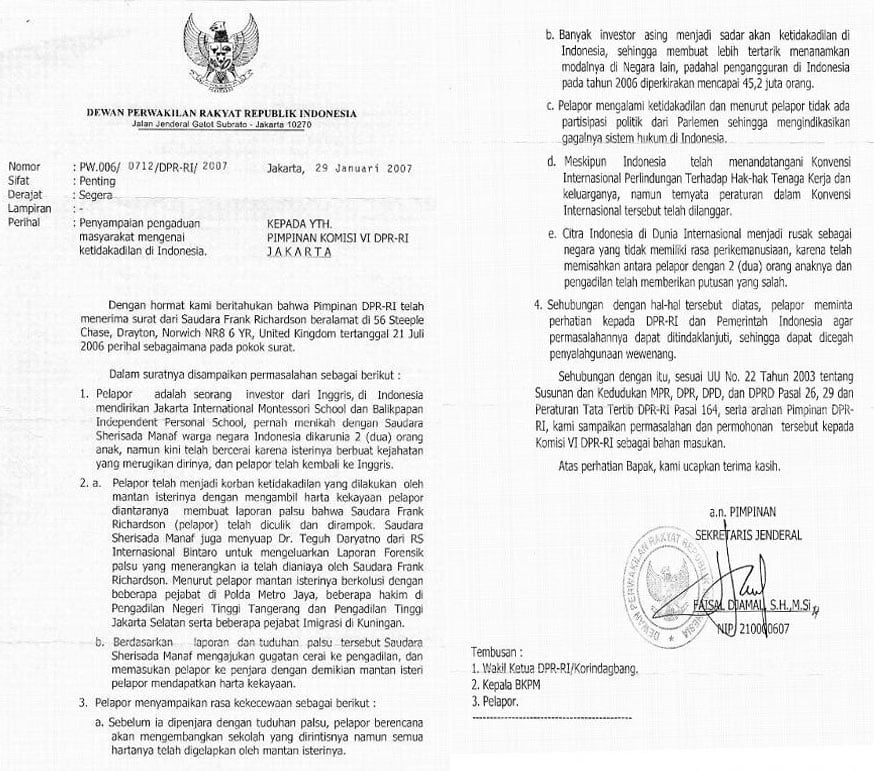

Englishman Frank Richardson learned the hard way that a foreigner can’t win when things start to go wrong. He had married Indonesian Sherisada Manaf in London in 1986. They moved to Indonesia in 1990 and in 1995 founded the Jakarta International Montessori School and later opened the Balikpapan Independent Personal School. There had been difficulties in their marriage for several years, but after Richardson declared that he wanted a divorce, he was arrested in 2002 on charges of assaulting Sherisada, who is a cousin of Jakarta Governor Fauzi Bowo and later became a Democrat Party official. Richardson, who was deported, says the charges were fabricated so that Sherisada could take the schools, their assets and custody of their children.

His advice to expats is to not be naïve and understand that normal ethics do not always apply. “Do not be too trusting of one’s Indonesian business partner or Indonesian spouse. That is not to say none can be trusted, but that there are many that one should be wary of,” he says. “Also, do not put all one’s eggs in the Indonesian basket; but ensure one has assets and funds securely kept overseas and be ready to leave the country, should one have to.”

Rather than just feel sorry for himself, Richardson has started a website called Open Trial (www.opentrial.org), which aims to expose and counter judicial corruption. “The best thing we can do to help ensure one does not fall foul of the Indonesian legal system is to help to strengthen the rule of law in the country through foreign and local businesses in Indonesia coming together and pressing for change. This is not something one can achieve alone; but I do hope that both Indonesians and expats will at least try to do this using the auspices of Open Trial.”

German Harry Bleckert in 2001 opened in Bali an internet cafe and web hosting/design company registered in his Balinese wife’s name, with himself employed as business development manager. Frustrated by the poor performance of local internet service providers, he decided to become a wireless service provider and in 2004 obtained a franchise agreement with a national ISP licensee. After purchasing necessary technical equipment, he began wooing prospective subscribers with his cheaper rates, much to the alarm of a major competitor. Days before the launch of his wifi service, police raided his office and seized the equipment on the grounds that it was unapproved. Later the company was accused of having equipment that was a “health risk” and an “environmental hazard”. Rather than pay bribes to end the harassment, Bleckert reported the matter to the Corruption Eradication Commission. Police responded by arresting his wife on charges of “unlawfully operating illegal telecommunications equipment”. Bleckert was later charged with criminal defamation for accusing the police of corruption. He fled the country with his daughter, and was later joined by his wife after she was released by Bali High Court.

In such cases, getting into lucrative niche businesses in Indonesia can upset existing operators, so it’s essential to go through all bureaucratic hoops to obtain correct documentation for every aspect of the business. An Indonesian PT (limited liability company) being run in proxy by a foreigner must stay within the limits of its initial activities and cannot start doing something else. If that happens, competitors will easily be able to engage the police and prosecutors to earn some money by shutting down the foreigner’s business, even if everything seems to have been done by the book. In Bleckert’s case, his wife’s business was not a PT but a CV (limited partnership), which is not so much a fully fledged company as merely a registered small business name.

Sometimes, it’s expats who target their fellow expats. Australian Barry Grossman in 2006 formed a PMA in Bali, supplying stone for building projects. To raise capital for expansion, he agreed to sell a 49% share in his firm to another Australian, builder Patrick Finlay, for US$980,000. Finlay paid about only 10% of the amount and then decided not to proceed with the deal. Grossman had spent much of the investment capital on quarry rights and claimed he could not go ahead without further funding. In 2007, Finlay filed a complaint with Bali Police, claiming he paid Grossman A$236,000 for an order of stone that was never delivered. Finlay had no contract for the alleged order and could not show bank transfers for that amount. A prosecutor who declared there were no grounds for criminal prosecution was removed from the case. Grossman’s supporters allege Finlay spent about $70,000 on payments directed toward law enforcement officials to have Grossman jailed. Finlay denied paying such bribes, but Grossman was in 2009 detained on charges of fraud and embezzlement. Released on bail after six weeks, he was banned from leaving the country. He fled in September 2010 to seek medical treatment and promised to return only if he can be guaranteed a fair trial. Indonesian police have requested his extradition from Australia and put him on Interpol’s Red Notice List, curiously on charges of forgery and counterfeiting.

There’s no easy way to avoid all of the pitfalls of investing in Indonesia. Getting on with people and officialdom is crucial. As is having a sound legal basis through a PMA, which can be established by consultancy firms for anywhere from $2,000 (firms offering this low price often come back to the client for more money to finish the process) to as much as $25,000 (charged by rip-off merchants calling themselves lawyers).

Is it worth getting a PMA solely to obtain a house? Gary Dean of Okusi Associates, which charges about $3,000 for setting up a PMA, says he’s often reluctant to recommend one for someone acquiring just a single residential property. “Having a company is a bit of a hassle for such relatively small investments; it’s not cheap to set up and maintain. There has to be tax reporting every month. But a PMA company is the only option for complete security.”

Dean, who founded Okusi in 1997 and has since set up over 1,200 companies, says foreign investors should realise a PMA isn’t a license to engage in large-scale property projects. “I get people coming to me every month wanting to do big property developments, and there’s no such investment category in Indonesia for foreigners as property development. You just can’t waltz in here and start buying up hectares of land and build things or do nothing with it.”

Foreigners looking for easy money in Bali, Lombok and other islands by “investing” in villas and then renting them out to tourists could find themselves in trouble, not least because many are not paying tax, but because they have upset established interests, such as the hotel industry.

People seeking help on property investment issues can wade through hundreds of pages of often conflicting threads on various expat forums and hope they get the right answers, or they can seek reliable advice from professionals. And if things do start to go wrong, then choose your battles wisely and know when to walk away from an injustice and start afresh, because the law is not on your side.

Notes on Indonesian Land Law:

http://okusiassociates.com/garydean/works/landlaw.html

http://www.expat.or.id/info/ownershiprights.html

http://www.aiccusa.org/landownership.html#foreign