Sharks are often painted as monsters, whilst the vast majority are shy and peaceful animals, fundamentally important to the ocean’s health. And the probability of being bitten by a shark while swimming or surfing is incredibly low.

Back in 1975, Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws” movie became one of the most successful motion pictures of all time. Leveraging on the people’s ancestral fear of big predators, one of the main results of this movie is keeping millions of people out of the water, imprinting on the audience’s mind the idea that sharks are cold-blooded assassins and that killing a shark is not such a bad idea.

This popular feeling, coupled with the increasing request of shark fin from the Chinese market for shark fin soup, have lead many shark populations close to their extinction.

Having a close look at actual numbers of shark attacks and related injuries, the reality is very different than perceived. According to the last International Shark Attack File (ISAF) report, in 2012 there were about 80 unprovoked shark attacks on humans. “Unprovoked” are defined as incidents where an attack on a live human occurs in the shark’s natural habitat without human provocation of the animal. So spear-fishers, shark riders and these kinds of interactions are not included in “unprovoked”.

Most of these episodes occurred in North American waters (42), followed by Australia (14), South Africa (4), and Reunion (3). A single incident was reported from Canary Islands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Tonga and Indonesia. Among these attacks, only seven resulted in a fatality (3 in South Africa, 2 in Australia, 1 in California and 1 in Reunion), following the trend of about 7% of fatalities since the data started to be recorded (approximately first decade of 1900, more than 100 years).

Apparently, many of the shark bites are made by mistake, both as a “tasting” from young individuals, or from adult sharks that have misidentified a surfer laying on his board on the surface as a seal, turtle or sea lion, some of their favourite meals. Surfers and other boat-sport participants were the most impacted in 2012, with 48 incidents. Swimmers and divers were also involved, but in a very low ratio. The so-called “Big Three” – Great White, Tiger and Bull Sharks – were responsible for about 90% of the total fatalities.

Apparently, many of the shark bites are made by mistake, both as a “tasting” from young individuals, or from adult sharks that have misidentified a surfer laying on his board on the surface as a seal, turtle or sea lion, some of their favourite meals. Surfers and other boat-sport participants were the most impacted in 2012, with 48 incidents. Swimmers and divers were also involved, but in a very low ratio. The so-called “Big Three” – Great White, Tiger and Bull Sharks – were responsible for about 90% of the total fatalities.

Even if these numbers would appear worrying at first glance, let’s investigate a little bit more in detail. I would not explain about how dangerous driving a car is in every country or, even worse, driving a motorcycle in Bali or Jakarta. Let’s remain in the natural world for these examples. In the USA only, in the last 50 years, about 2,000 people died from a lightning strike, compared to the only 26 shark attack fatalities. In southern USA, in the same period, 18 people died by an alligator attack, and only nine by shark bite. In Florida, 125 people died as results of tornadoes, compared with six shark attack fatalities.

If you still think that sharks are terrible killers, you might be interested to know that in the last 10 years in the USA, 263 people died by a dog attack, and sharks killed only 10. And in New York City alone, approximately 8,000 people are bitten from another human (!) and some of them even die.

Having a look at all this data, it’s clear that the diffused “shark dread” is more a society and media-induced fear than an actual risk. Some very low-level movies like “Sharknado” (a tornado of sharks hitting Los Angeles), “Sand Sharks” (sharks swimming below the sand eating people on the beach) or even “Shark Avalanche” (sharks attacking skiers swimming below the snow) have been produced, hoping to arouse these ancestral fears (with low success, I have to admit – watch the trailers on YouTube).

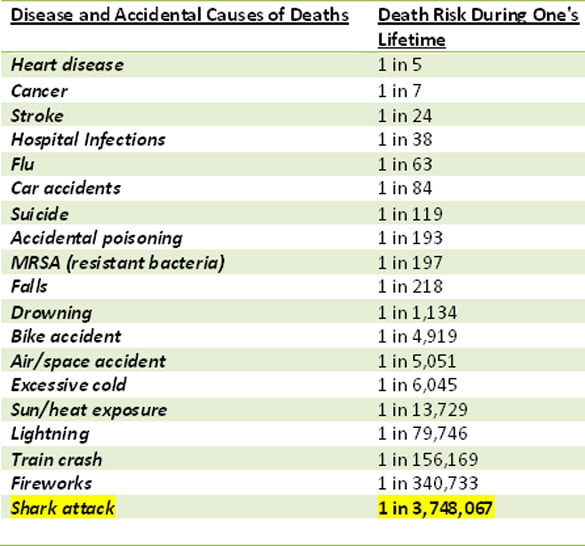

Annual Risk of Death During One’s Lifetime. Source: International Shark Attack File

Millions of sharks are killed every year for their fins and meat. Several international scientists have already pointed out that such removal of “apex predators” from the oceans may cause irreversible damage on these fragile ecosystems, already threatened by many other factors, including chemical and plastic pollution, waste disposal, climate change and overfishing, just to name a few.

In Bali especially, to find a shark during a dive or from a boat has become a very uncommon experience. Indonesia is one of the main shark and ray fisheries in the world, especially in waters surrounding Lombok and Bali. Some attempts at creating social awareness about the shark’s disappearance are already working very well. Apparently the demand of shark fins has decreased in recent months, and some organizations in Singapore and Hong Kong are proposing strong campaigns against the shark fin soup tradition.

Something is moving in Indonesia as well. Some of the more important diving destinations, like Komodo and Raja Ampat, are declaring their waters “Shark Sanctuaries”, where fishing these animals is strictly forbidden. Of course, poachers are always on the prowl, but it is becoming more difficult for them to operate than before.

Something is moving in Indonesia as well. Some of the more important diving destinations, like Komodo and Raja Ampat, are declaring their waters “Shark Sanctuaries”, where fishing these animals is strictly forbidden. Of course, poachers are always on the prowl, but it is becoming more difficult for them to operate than before.

Organizations like Bali Sharks (www.balisharks.com) and the Gili Shark Foundation (facebook.com/gilisharkfoundation) are raising awareness among tourists and locals about the importance of keeping Indonesian sharks alive. The Thai-based UK Charity, Shark Guardian (www.sharkguardian.org) has just finished a two-week tour visiting schools and dive centres/resorts in Sanur, the Gili islands and Nusa Lembongan. The Directors, Brendon Sing and his wife Liz, have been educating more than 17,000 people since February this year when they committed to their projects full time. They have visited Hong Kong, Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia in this time, as well as locations throughout Thailand. Through educational presentations and workshops on sharks and marine life they aim to inspire change and get people involved in shark conservation. Shark guardians visited Bali International and Dyatmika schools to talk to the students. They also presented to more than 30 women at Bali Wise in Nusa Dua, demonstrating how important sharks are for maintaining long-term tourism benefits on Bali. Divers and tourists were the target of the local islands and in total around 500 people saw Brendon and Liz in action during their time in Indonesia.

With everyone’s involvement and help, we can stop the fear of “Jaws” and guarantee a brighter future for our oceans.