The soft scent of cloves toasting underneath the sun wafted in the air as my ojek cruised over the lush green hills of Minahasa Tenggara. The road outlooks a trapezoid hill plunging into a mangrove-laced cove, glittering with shades of blue and green. From afar, I could see speckles of light and dark colours in the water, suggesting the presence of lively reefs underneath.

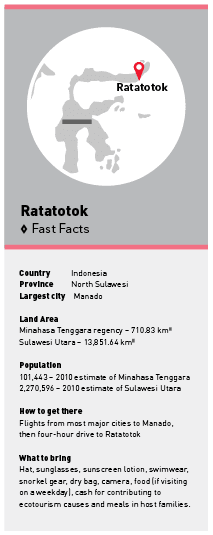

These were my first sights of Ratatotok. The first stories I heard of this coastal settlement associated it with the Buyat Tragedy, a highly publicised 2004-2007 case alleging a multinational gold mine’s involvement in polluting Buyat Bay to the point of a baby girl’s death.

That said, friends from North Sulawesi have been raving of Ratatotok’s beaches and dive scenes. “Better than Bunaken,” several have told me.

Today, years after the mine closed down, its legacy is still ubiquitous in Ratatotok-Buyat, as are lingering sentiments among locals.

58-year-old seasoned fisherman Rusdin does not normally take tourists, but took us to some mangroves growing on elevated reefs. He switched off the motor as we floated over clear shallow waters brimming with underwater life.

I snorkelled into a realm of purple table corals, round pink brain corals, yellow staghorn corals and schools of small colourful fishes. It looked all-natural and pristine to me, more so than the ones I snorkelled in the Togians. But I sensed that what I saw was not the whole story.

“Looks like your coral reefs are recovering well after the mine stopped operating,” I remarked. “Are any of these the artificial reefs planted by the company for post-mining rehabilitation?”

“We’re at the wrong beach,” replied Rusdin. “These reefs are natural. Still, the pollution persists because even after the big mine shut down, there are still many local artisan miners. But then they’ve been around longer than the big mine. And there are many damaged reefs in Buyat whose recovery I’ve yet to see.”

“We’re at the wrong beach,” replied Rusdin. “These reefs are natural. Still, the pollution persists because even after the big mine shut down, there are still many local artisan miners. But then they’ve been around longer than the big mine. And there are many damaged reefs in Buyat whose recovery I’ve yet to see.”

Before the multinational company started operations, Rusdin could expect to catch Rp.300,000 worth of fish on a bad night. Today, he considers it a good night if he can make Rp.200,000. He says local fishermen and artisan miners are on good terms despite their opposite interests. “They’re simple locals trying to make a living, just like us,” said Rusdin. But different standards apply when it comes to the company, even if it adheres to more stringent environmental regulations.

According to Syafrudin Wangko, chairman of the Coordinating Body of Mining-Impacted Communities (BKMKT), part of the resentment towards the company stems from the fact that government regulations tend to favour big businesses rather than humble locals, and that these businesses tend to contribute to the government rather than the communities themselves.

Wangko says that the damage in Buyat Bay has been extensive and caused public health hazards. Hence tourism promotions have been focused in Ratatotok where the aesthetic impacts of the pollution are barely visible.

“We don’t know what happened to the artificial coral reefs. They would likely be buried under thick mud by now, and the ongoing pollution generated by current artisan miners would make it difficult for natural coral to recuperate,” says Wangko. In Ratatotok, the company could conveniently present pictures of vibrant coral reefs and take credit for post-mining environmental remediation before stakeholders who know next-to-nothing about marine ecosystems.

That said, Wangko gives credit to the company for socio-economic development in Ratatotok throughout its operations and beyond. The company’s US$30 million community development funds have provided much appreciated schools, houses of worship, infrastructure, a well-equipped hospital, and aid for local fishermen and small businesses.

Wangko also says that a greater current priority is educating artisan miners to practice safer and more responsible mining, or empowering illegal ones to migrate to other professions altogether. “Being a humble local trying to make a living does not excuse one from damaging the environment at the expense of everybody else and the next generation.”

Wangko also says that a greater current priority is educating artisan miners to practice safer and more responsible mining, or empowering illegal ones to migrate to other professions altogether. “Being a humble local trying to make a living does not excuse one from damaging the environment at the expense of everybody else and the next generation.”

Wangko does not buy into the idea that tourism is a reliable and sustainable alternative livelihood. Tourism is seasonal by nature and requires capital, skills, and experience that Ratatotok locals currently do not have.

Muhammad “Pudin” Saifuddin, founder of the Ratatotok-based Ecotourism Volunteer Group disagrees. Since 2012 it has been his mission to raise awareness of environmental and conservation issues in Ratatotok-Buyat and identify economic opportunities for locals through the tourism industry. The group was established out of concern for the disunity among pro-mining and anti-mining residents of Ratatotok, and as an attempt to engage the grassroots community in sustainable solutions.

“I cannot say whether the environment is damaged. I’m not a scientist. But we identify ecotourism opportunities to empower locals despite the limitations,” said Pudin. That says, he acknowledges the Minamata Institute’s findings of high mercury levels in the estuary of Totok River due to the presence of artisan miners stemming back from before the big mine. He adds that during the mine’s days, tourism in Ratatotok-Buyat actually developed better because it funded small businesses in Lakban beach and the cleanup of nearby islands.

“As far as fishermen are concerned, when the fish population is depleted, the sea is polluted. But fishermen often forget that they sometimes contribute to the problem. They catch fish in coral reefs and damage them with their anchors. And in the past, neighbouring villages have bombed for fish,” explained Pudin, adding that Ratatotok has been bomb and potassium-free for a dozen years now.

The group’s activities include organising shops in Lakban beach, setting up environmental awareness billboards in the islands, making coral-friendly floating anchors for fishermen, and arranging tours for visitors.

To attract international support and educate local fishermen and tourism micro-enterprises, the group invites travel bloggers and tourists to document the marine and terrestrial beauty of Ratatotok-Buyat and their satellite islands.

Ratatotok-Buyat has identified 24 dive sites. A commercial dive operator from Lembeh organised dive tours there, but stopped due to difficult logistics and the absence of resorts. A typical itinerary includes snorkelling, a bentor (pedicab) tour to the tuna smokehouse, trekking in the mangroves, sightseeing from a hilltop and unwinding the day in a cafe at Lakban. Pudin offers a room for visitors in his humble family home and would guide for free, but asks each visitor to plant a mangrove tree in return.

Pudin can be contacted on 081244582923 and is on Facebook as “Cak Pudin.”