Jakarta’s Climate Change: Wet to Dry and Dry to Wet

A fortnight ago the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its fifth assessment report, a weighty tome of a million words or more that reiterates what it said in its fourth assessment report published six years ago; namely that the experts are now 95 percent certain, as opposed to 90 percent before, that the observed warming of the planet is caused by the increase in atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) due mainly to man’s burning of fossil fuels. After the inevitable media fanfare at the launch and the predictable for and against arguments from the main contestants – the anthropogenic (man-made) warming lobby and their nemesis, the climate change deniers – the media has gone remarkably quiet over the issue reflecting, perhaps, the public’s total disenchantment with this sterile debate.

Weather is an important and everyday component of our lives and, if you’re British, varies from being a conversation gambit to an obsession. In Indonesia in the month of October, and under normal circumstances, the long-suffering citizens of Jakarta would be preparing for the start of the wet season, which would see a few small showers early in the month with heavier, more frequent showers towards the end as the season, which gets well and truly underway in November. For generations, West Java’s farmers have begun to prepare the land for wetland rice cultivation in October in anticipation of the start of the heavy rains in November.

That was until a few decades ago when the onset of the wet season became less regular and more unpredictable. The start of the wet season and the likelihood and timing of the torrential downpours that cause deep and prolonged flooding in the capital are of far more importance to farmers and city dwellers than the 0.05 0 Celsius rise in the world’s average surface temperature that may or may not occur over the next decade if we continue burning fossil fuels.

What does the IPCC’s report tell us about the likely regional variability of climate, for we all live in specific regions, each with different regional climate that ranges from icy cold Arctic conditions, through to the hot, humid tropics, with belts of temperate zone climates in between, leavened with deserts, mountains and, in the case of Indonesia, thousands of islands? (In the latest update of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system, 31 different climate classes are recognized.) The report doesn’t actually say very much that is going to help either the Javanese farmers predict the onset of the wet season or the timing of the heavy tropical downpours. What it concludes is that dry regions are likely to receive less rain and wet seasons more rain. Well, the latter certainly seems to be happening in Lebak Bulus!

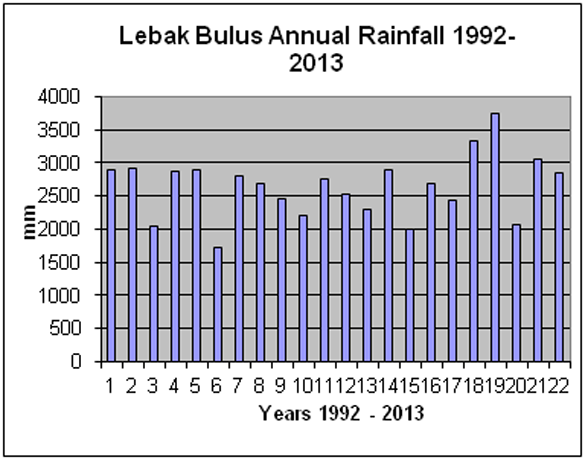

Among my many hobbies, one is peculiarly British and somewhat eccentric; I measure the daily rainfall in my garden at Lebak Bulus, South Jakarta and have done so continuously since 1992, a period of record spanning 22 years. I use a metric-calibrated rain gauge that is located in an open position, free of any biasing influence such as overhanging trees or shrubs. This in itself does not make me an expert on meteorology or climate, but since I studied meteorology and climatology at university as part of natural science graduate and postgraduate studies, and have worked as a soil scientist for 40 years in at least half of the world’s regional climates, it probably makes me more qualified both to understand and comment objectively on the great ‘global warming’ debate or, as it is now referred to, the ‘climate change’ debate than the thousands of bloggers of both persuasions, who regularly pontificate on this incredibly complex subject with little or no background in the relevant basic sciences.

The trend for the past 22 years in Lebak Bulus, as the accompanying graph shows, has been for wetter, longer wet seasons and wetter dry seasons with fewer dry months (< 100 mm). The wettest three years in 22 years of record (> 3,000 mm) was in 2010, 2011 and 2012. This year seems set to continue this trend, with some 2,837 mm of rain falling between January and the end of September. The average rainfall for the months of October to December between 1992 and 2012 (21 years) is 730 mm +/- 258mm therefore it is more than 99 percent certain that we will receive in excess of 3,000 mm of rain in Lebak Bulus in 2013. In those three very wet years, there was effectively no dry season in South Jakarta and many farmers complained of ruined harvests because of excessive rain during the months of June to September.

The actual climate mechanisms causing this are probably related to the strength and track of the NE and SW monsoons; the seasonal winds (NE, NW, SW and SE trade winds) that drive the weather systems in the tropics, the occasional southward drift of the northeast Asian cyclone or typhoon belt, and the preponderance in the last eight years of La Nina conditions in the Pacific Ocean, all of which may or may not be influenced to some degree by atmospheric CO2 levels. To be fair, to the much maligned General Circulation Models (GCMs), which form the basis of the IPCC long-range predictions on climate world-wide, most models, despite not having predicted the leveling off in global warming over the past 17 years, do predict the occurrence of major changes in precipitation patterns in the monsoon areas of Asia, with many areas in the wet tropics, including Indonesia, receiving more rain more frequently and in heavier downpours.

Whatever the cause of the variations in the weather, it is clear that local climates are changing, some for the better others for the worse. This is not a new phenomenon, but merely reflects the cyclical changes in weather and its longer-term counterpart, climate that have been occurring over centuries, millennia, and millions of years. Higher levels of carbon dioxide levels probably play a part, especially in helping re-green the planet, but the physics and chemistry of the atmosphere and its interface with the oceans and land masses, is highly complex and only partially understood, as the latest IPCC Report grudgingly admits. The claim from the UK Chief Scientist a decade ago that the science of climate is settled is a long way from the truth, but then as Wiltshire farmers say, “there’s no debt so surely met as wet to dry and dry to wet”.