“The philosophy of the school room in one generation will be the philosophy of government in the next.”

– Abraham Lincoln-

On National Education Day, May 2nd, Minister of Education and Culture, Mohammad Nuh, said: “The national exam plays only a little part in the country’s education system. The most important thing is to ensure that all children receive education services.”

Since 2008, spending on education has been set at 20 percent of the total budget thanks to a constitutional amendment. The 2013 state budget for education shows an increase of 6.7 percent to Rp.331.8 trillion ($34.9 billion) from the Rp.310.8 trillion allocated in 2012, and is above the mandated 20 percent of anticipated government state revenues (Rp.1,508 trillion)

As reported in the Jakarta Globe, President Yudhoyono said that the budget would be used to continue the School Operational Aid (BOS) program for elementary and junior high school students, build 216 new schools while renovating hundreds of old ones, as well as to support the Scholarship for the Poor, which is aimed at 14.3 million indigent students across the country.

“We will also launch the Universal Secondary Education program (PMU) through school operational aids for 9.6 million high school students. We must make the most of the growing education budget to improve the quality of education and expand the outreach of it.”

However, only Rp.66 trillion, just under 20 percent of the total, is allocated to the Education and Culture Ministry, with most of the money set to go directly to other districts through programmes such as BOS and PMU.

It is clear from World Bank stats published last year, but only given up to 2010, that in some areas improvements have been made. For example, the primary school (SD) pupil-teacher ratio (the number of pupils per teacher) was down to 15.97 from 20.41 when President SBY was first elected, while the secondary schools’ (SMP and SMA) pupil-teacher ratio was reduced to 12.18 from 14.2.

However, these figures are distorted because remoter areas of Indonesia, which commonly lack electricity, running water and/or telephone coverage, suffer from a shortage of teachers. The figures also do not take into account teacher absenteeism of around 20 percent because many in the public school system have to take second or even third jobs to supplement their meagre incomes.

What the teachers provide is determined by the national curriculum set by each incoming Minister of Education. The country is about to have yet another imposed on students and teachers, its third in just ten years. The nett result, as shown by The Learning Curve, an “analysis of school systems’ performance in a global context” from the Economist Intelligence Unit, is that Indonesia is at the very bottom of 40 ranked countries, including Hong Kong. Key benchmarks were, among others, knowledge comprehension, teaching standards and the graduation rate. Since the last survey in 2006, the cognitive skills in Maths and Science have regressed.

A main stated reason for the new curriculum is to reduce the number of subjects that students are taught; some senior high school students are currently expected to study as many as seventeen (yes – 17) subjects in one year. Minister Mohammad Nuh argued that an emphasis on an integrative thematic method was “suitable to promote students’ cohesive thinking and to boost their entrepreneurial skills.”

If “cohesive thinking” means an understanding of inter-connectedness and the nature of consequences, then one can but agree. However, this understanding can only be achieved through the exploration and development of personal interests and talents and a curriculum which encourages creativity and understanding within a communal, pluralistic context.

Howard Gardner, who developed the theory of Multiple Intelligences, argues that “students will be better served by a broader vision of education, wherein teachers use different methodologies, exercises and activities to reach all students, not just those who excel at linguistic and logical intelligence.”

As for “entrepreneurial skills”, having recently witnessed the activities at Sumur Batu, Bekasi’s landfill for its rubbish, it was obvious that the vast army of workers there have those skills, albeit without having received formal education, if any, beyond elementary school. Here on the streets of Jakarta, the hawkers galore, peddling plastic household supplies or vending ‘meals on wheels’, the corner kiosks and food warungs, and the unofficial parking attendants are all evidence of entrepreneurial endeavour.

Where it is lacking, I suggest, is within the corridors of power.

Writing in the Jakarta Post, Donny Syofyan opines: “While the country’s formal schooling system remains centralized, rigid and resistant to innovation from the public, various movements and alternative educational innovations currently springing from the grass roots should be appreciated as representing civic resistance and disappointment.”

Of course, a major reason for disappointment has been the recent cock-up of the distribution of the question papers and answer sheets for the Ujian Nasional, the national exams, which, in spite of an inflated budget, arrived days late for senior high school students in eleven provinces. Calls have been made for the Minister to resign, yet few have offered an analysis of the exams themselves. Teachers detest having to teach to them, partly because they are reflections of the narrow mindsets of the bureaucrats who write them – and fail to check them.

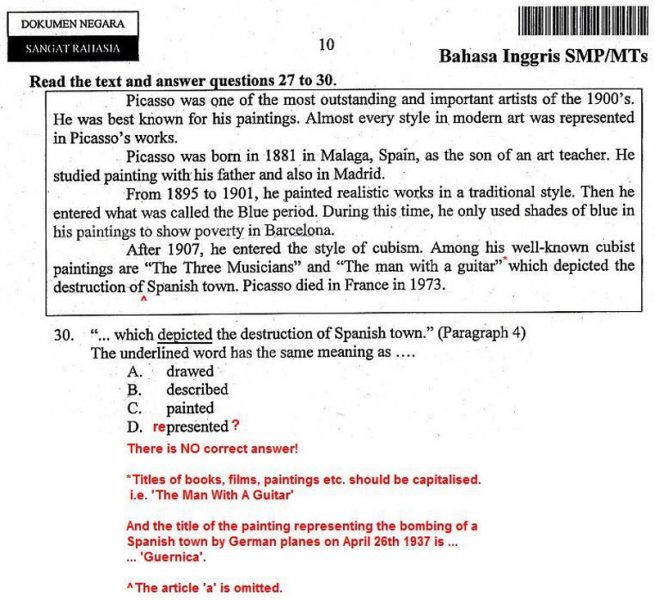

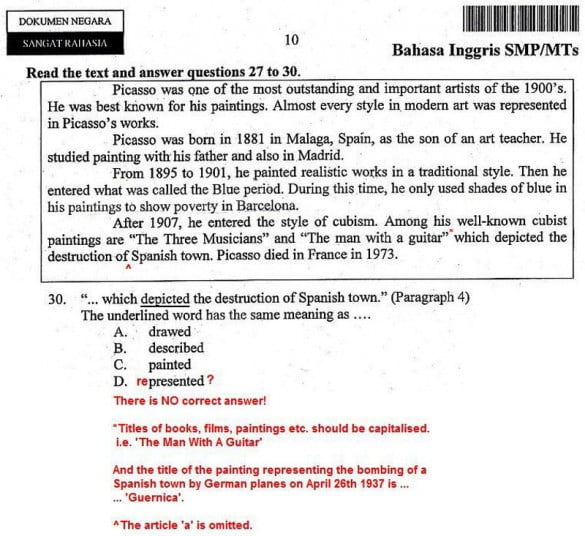

This is but one example taken from one of the up to twenty versions – to prevent cheating it is said – of the recent junior high school English exam.

I now call the UN the UM – the Ujian Monyet.

Apasi, apasi?

Scratches head, grunts – A-B-C-D?

Ah, ini!

On May 1st, former vice president Jusuf Kalla defended the National Examination (UN) as the enhancement of education in Indonesia. He said it took 10 years for a perceived policy impact.

Need we wait that long?