The second subject of Hoffman’s book is Michael Palmieri, an opportunistic, adventurous buccaneer who rode the crest of the wave of disenchanted youth who travelled to Asia in the 60s and 70s. He eventually discovered the wild beaches of south Bali in the early 70s, still quite a few years before the crowds arrived. He travelled into the hinterlands of Borneo, up the rivers and their tributaries to visit remote longhouses. Unlike Bruno, he was not driven by a desire to “live in the belly of the mother” with primitive people of the forest. He enjoyed his adventures, he enjoyed pushing further into unknown territory than those around him, but primarily he was looking for treasure, for wood carvings, masks, totems, any object that could satisfy the booming demand for “primitive art.”

It’s an odd juxtaposition. Hoffman’s story jumps back and forth, in alternating chapters, between the lives of these two men, with the author describing the paths by which the two men arrived in Borneo, the impact it had on their lives, the manner in which they navigated or failed to navigate the dramatic changes that have affected the island over the decades, and the parts they played in ushering in these changes. Their lives barely touched each other. They met only once, by chance, in a restaurant, where they had an inconsequential conversation. Their lives took very different trajectories.

At the time when Bruno went off to the forest to join the Penan, Malaysia’s logging industry was undergoing a massive expansion, destroying much of the forest in which the community lived, with little compensation paid or recognition given to their rights to the land. Bruno began organising the people against the logging companies and government agencies, demanding moratoriums and reservations, smuggling out petitions and manifestos, and conducting flamboyant stunts as a guerilla activist that attracted global attention. While he became a hero and icon to the movement, his efforts were largely futile. Logging continued, most Penan people settled and more or less integrated into the bottom rung of modern rural Malaysian society, their traditional way of life fading to memory. In 2000, Bruno disappeared into the forest, never to be seen again. He is almost certainly dead, despite a few wishful fantasies that he has become some kind of phantom.

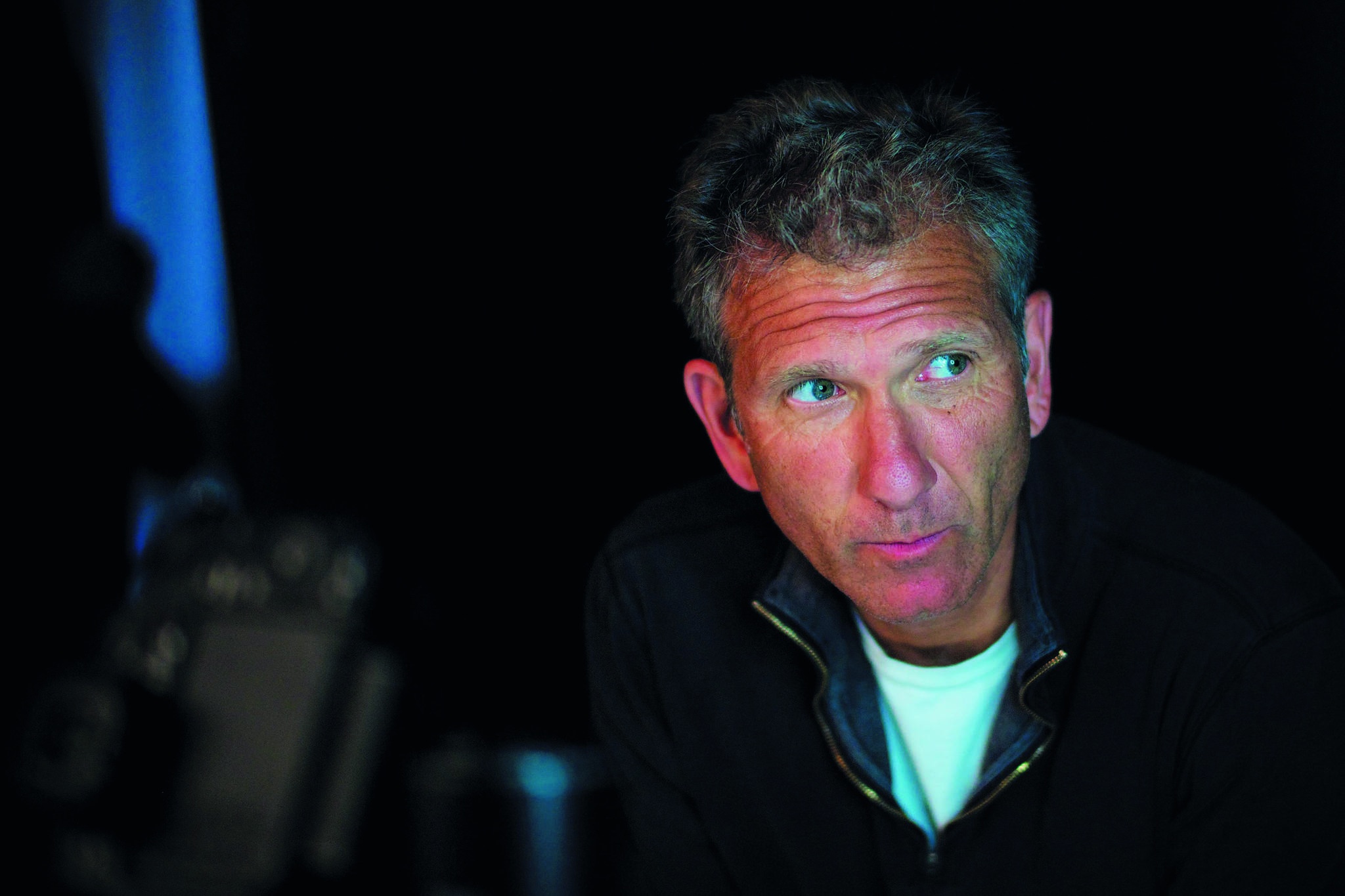

As an art dealer who got in early, Michael Palmieri has ended up as one of the more successful collectors and dealers of indigenous Dayak art in the world. He has become something of a lightning rod for the collective guilt attached to cultural appropriation and exploitation, often despised and disliked by those who now hold him partially responsible for changes around the world that were vastly bigger than the actions of a single man. He continues to live in Bali, a place that now bears little or no resemblance to the one that first drew him there. The rivers are mapped, the treasures largely exhausted, and the longhouses gone. He can never really return to America, but his place in his new home is ambiguous and marginal. But at the same time, he has survived and found a way to evolve.

Hoffman uses the incongruous juxtaposition to explore themes related to the fascination of people from rich, developed societies with primitive societies. Hoffman’s previous book was an investigation into the disappearance in 1961 of Michael Rockefeller, a descendant of one of the richest families in America at the time, on a trip to acquire the art of the Asmat tribe, an isolated community who live in the swamplands and lowland rainforest on the southwestern coast of bordering the Arafura Sea. Until very recently, the Asmat have had limited interactions with the outside world, and their attachment to their traditional way of life remains strong.

During his stay with the Asmat to investigate this story, Hoffman came to reflect deeply on his own fascination with isolated, wild people. More generally, he came to reflect on the persistent obsession of modern society with the idea of wild people who have not been corrupted by civilisation. Stories about an uncontacted tribe in the Amazon, on the Sentinelese islands, or anywhere else thrill and enthrall. The very fact that we don’t know and can’t understand makes it possible for us to construct any story we like. As Hoffman says, we use tribal people as blank slates on which to project our own needs and desires. Going all the way back to Rousseau’s idea of the Noble Savage, the need for people on whom we can project these needs and desires is perhaps now becoming even stronger with the increasing shortage of people on whom these fantasies can be projected.

While Hoffman had been aware of Bruno’s story for decades, it was a chance meeting with Palmieri at the Ubud Writers’ Festival that determined him to use the stories of the two men to investigate these themes. Both of the men, wittingly or unwittingly, pandered to the fantasy, the obsession with primitive people. Bruno seemed to be able to enter the forbidden kingdom, with many thousands of people around the world idealising him and holding him up as a hero, living the fantasy vicariously through him. Bruno himself may have wanted to become one of the Penan – but everyone else just wanted to be Bruno, the white man who gains admittance to the forbidden kingdom. Unable to learn the skills or tolerate the discomfort of living in the forest themselves, he was their key to that world. As Hoffman says, it is always Tarzan who is the hero, never the indigenous people themselves. They are merely the backdrop for the fantasy world in which Tarzan lives. Palmieri pandered to the same fantasy by selling works of art from that kingdom, enabling people to gain entrance to the kingdom in a very different way.

In his book, Hoffman maintains his focus on his two main characters, keeping his presence as the narrator light-handed. But in the final section, he emerges from the shadows to describe his own journey, with Michael, to partially retrace the journeys of Michael’s youth, into Kalimantan. They start in Bali, where Hoffman sees the swarms of tourists who pour onto the island, attending shamanic drumming workshops, taking snaps of tooth filing ceremonies and creations, shooting selfies of themselves performing asana in front of temples. Hoffman realises that the thirst and longing for the traditional old ways is a fundamental hypocrisy: “We only wanted it when it suited us, for we wanted our freedom too. We came, we ogled, we left.” It is the people of our fantasies who pay the price. Hoffman realises that Bruno wanted to preserve the forests of the Penan so that they could live his dream, not their own dreams. And Bruno could always leave.

By the end of the book, in Hoffman’s eyes, Bruno is less the saint that Hoffman imagined when he began his journey, and Michael is much more human and likeable. In the final chapters, Hoffman quotes an old friend of Bruno’s, Georges Ruegg, who says: “The art of life is to grow old, but not to lose your beliefs as you do. Or if you lose them, to find new ways to be glad to be alive.” Bruno’s tragedy, he says, was that he couldn’t evolve. In the final pages of the book, Hoffman hears from “the formerly handsome” Palmieri, now an old man with hearing aids. He is happy to be coming home to Bali, to the life he has created for himself there, despite his decaying body and the changes around him. He is no saint and no hero. But at least he has found new ways to be glad to be alive. In the end, perhaps we can learn more from Michael than Bruno. Learning to grow old gracefully in a changing world is perhaps a far more deeply profound skill than living a life of pointless martyrdom to a fantastic vision of a world that never really existed in the first place, except in our own imaginations.