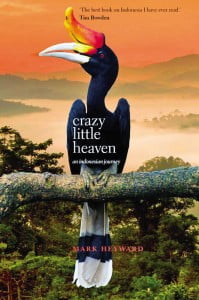

Mark Heyward

Pub. Transit Lounge Publishing 2013

ISBN: 978-1-921924-507

“One’s destination is never a place but rather a new way of looking at things.”

– Henry Miller

My bookshelf has a number of tales written by travellers through Indonesia; from Geoffrey Gorer in the mid ’30s (Bali and Angkor), to Norman Lewis (An Empire of the East – 1995), Redmond O’Hanlon (Into the Heart of Borneo – 1983), and George Monbiot’s Poisoned Arrows – 1989.

My bookshelf has a number of tales written by travellers through Indonesia; from Geoffrey Gorer in the mid ’30s (Bali and Angkor), to Norman Lewis (An Empire of the East – 1995), Redmond O’Hanlon (Into the Heart of Borneo – 1983), and George Monbiot’s Poisoned Arrows – 1989.

However, these were written by folk who came, observed, and then departed for pastures new, and not by someone who is the patriarch of an Indonesian family and has clocked up nigh on two decades here.

With his fellow Tasmanian wife and their two young children, Mark Heyward arrived in East Kalimantan in 1992 to teach at an international school for the children of expatriate miners. He had a certain wanderlust inherited from his family’s folklore and so he was not the first to leave Tasmania, that far-flung corner of the Commonwealth, for the tropical forests of Borneo.

In 1994, seeking “a little adventure in [his] own life” with three companions, he set out to cross Kalimantan from his home base in Sangatta to Pontianak in the southwest. His journal of the seventeen day adventure, recounting travelling by taksi air (water taxis, “the local public transport”), climbing mountain ridges, trekking through forests, wading across streams and exploring cave systems in isolated areas, forms the core of the book.

A year after his “adventure”, he returned to Tasmania, a divorce, and further study. As the subject of his PhD was ‘intercultural literacy’, returning to Kalimantan seemed natural, and it was at his old school that he met his future wife. Although currently based in Jakarta, where Mark works as an educational consultant for an international NGO, their home is in Lombok, where they have a studio, “a comfortable eco lodge”, and have helped set up a school for local children which invokes gotong royong (“community action”).

I’d only had time for a quick dip into the book before Mark and I first met up for a chat over a few Bintangs but, with delighted recognition, I had already realised that we were on the same page of different books.

Mark described his journal to me as “a little bit naive” and in writing a Tasmanian magazine article, which ended up as “half a book”, he realised that his “journey of a lifetime” was just part of a life’s journey.

And that becomes clear when reading Crazy Little Heaven. Although the journey across Kalimantan forms the main structure, it is divided into seven parts which act as pegs. These have allowed Mark to reflect not only on the ‘then’ but also on where it has led him; to the ‘now’.

And that becomes clear when reading Crazy Little Heaven. Although the journey across Kalimantan forms the main structure, it is divided into seven parts which act as pegs. These have allowed Mark to reflect not only on the ‘then’ but also on where it has led him; to the ‘now’.

For example, in Part 5, the trekkers come across an isolated Dayak family whose sole occupation, it seems, is to harvest birds’ nests from caves in limestone outcrops by clambering up precarious bamboo scaffolding. However, “while in the past birds’ nest were obtained exclusively from remote locations like this, more recently enterprising locals have begun farming the birds” for a “burgeoning Chinese market”.

Mark writes movingly about his visits to the orangutan rehabilitation centres founded by Willie Smits, the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (BOS), and Biruté Galdikas who founded Camp Leakey.

“With our greed and appetite for progress, our cruelty and inability to share the planet with other creatures, we have become a destructive plague. Looking into the eyes of a young orangutan threw this into stark relief. Is his the last generation?”

Perhaps Mark’s journey is not so much myth-making as in placing his own in the context of the many myths westerners cannot grasp here. In order to conform to Indonesia’s marriage laws, Mark converted to Islam. In Part 6, Rapids and Religion, he offers an extensive ‘critique’ of religious ethical codes as practised here.

He witnessed the fatalism – Inshallah (God willing) – of Muslims in Aceh six months after the tsunami, yet I knew two parents who, having lost three of their four children to the waves, subsequently died of heart break.

His own sense of spirituality has led him to climb many volcanoes throughout the archipelago. On Gunung Inerie on Flores, which is a predominantly Catholic island, he had a sense of awe and wonder.

Standing on that peak, nothing around us but sharp, slender air, a strange stillness, the roaring silence prompted me. Turning to our local guide I asked, “Can you hear it? Can you hear the voice of God?”

“Nope,” he replied, with a puzzled look.

He later “wonders whether we should be looking beyond the Abrahamic religions for a spiritual basis for the environmental ethic we so desperately need.”

At the recent book launch in Kemang, a local journalist asked Mark, “What’s in it for Indonesian readers?” His answer was that he hoped it would help Indonesia-Australia relations.

A worthy aim, but as he told me, “Writing is an act of making meaning, sorting out the chaos, myth-making; and the primary audience is oneself.”

I suggested to Mark that because his journey as a young man had set the context of his life, perhaps the book served as a closure.

After 20 or so years spent travelling around the islands of Indonesia he said that “Indonesia has become me. The more Indonesia becomes comprehensible and ‘normal’, the more I appreciate the beguiling mix of contradictions and ambiguities; a sweet disappearing world.”

“Living and travelling in Indonesia teaches you nothing if not flexibility in thinking.”

How very true.